Full Name: JAMES KENNETH CANIFORD

- Date of Birth: 8/26/1948

- Date of Casualty: 3/29/1972

- Home of Record: FREDERICK, MARYLAND

- Branch of Service: AIR FORCE

- Rank: SMS

- Casualty Country: LAOS

- Casualty Province: LZ

- Status: MIA

Airmen MIA From Vietnam War are Identified

The Department of Defense POW/Missing Personnel Office (DPMO) announced today that the remains of four U.S. servicemen, missing in action from the Vietnam War, have been identified and will be returned to their families for burial with full military honors.

They are Major Barclay B. Young, of Hartford, Connecticut; and Senior Master Sergeant James K. Caniford, of Brunswick, Maryland. The names of the two others are being withheld at the request of their families. All men were U.S. Air Force. Caniford will be buried May 28 in Arlington National Cemetery near Washington, D.C., and Young’s burial date is being set by his family.

Remains that could not be individually identified are included in a group which will be buried together in Arlington. Among the group remains is Air Force Lieutenant Colonel Henry P. Brauner of Franklin Park, New Jersey, whose identification tag was recovered at the crash site.

On March 29, 1972, 14 men were aboard an AC-130A Spectre gunship that took off from Ubon Royal Thai Air Force Base, Thailand, on an armed reconnaissance mission over southern Laos. The aircraft was struck by an enemy surface-to-air missile and crashed. Search and rescue efforts were stopped after a few days due to heavy enemy activity in the area.

In 1986, joint U.S.- Lao People’s Democratic Republic teams, lead by the Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command (JPAC), surveyed and excavated the crash site in Savannakhet Province, Laos. The team recovered human remains and other evidence including two identification tags, life support items and aircraft wreckage. From 1986 to 1988, the remains were identified as those of nine men from this crew.

Between 2005 and 2006, joint teams resurveyed the crash site and excavated it twice. The teams found more human remains, personal effects and crew-related equipment. As a result, JPAC identified Young, Caniford and the other crewmen using forensic identification tools, circumstantial evidence, mitochondrial DNA and dental comparisons.

Jimmy Caniford would have been 60 in August.

But, instead of growing into middle age, getting married, having kids and grand kids, Caniford died when his aircraft was shot down over Laos on March 29, 1972, five months before his 24th birthday.

His body was not recovered, and for 36 years, he was listed as missing in action.

Last month, Caniford’s family learned his remains had been recovered at the crash site. He will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

“This means we’ll finally have a place to go where he’s going to be,” Caniford’s father Jim of Fort Myers, Florida, said. “The overworked expression ‘closure’ is the one I want to use. It’s a finalization of the unknown we’ve lived with for so many years.”

As soon as he graduated from Middletown High School in Frederick County, Maryland, Jimmy Caniford enlisted in the Air Force at the age of 17 — he had to get written permission from his parents.

After basic training, he volunteered to fight in Vietnam.

As an AC-130 Hercules gunship illuminator operator, Staff Sergeant. Caniford flew missions over Vietnam out of the Philippines — the AC-130’s primary missions were close air support and armed reconnaissance; the illuminator operator’s job was to shoot illumination flares, watch for enemy anti-aircraft positions and drop smoke to mark targets for F-4D fighters.

When his enlistment was up, Caniford re-upped and was assigned to the 16th Special Operations Squadron at Ubon Air Force Base in Thailand.

“He believed 120 percent that we were doing the right thing in Vietnam,” said Caniford’s sister Diana DiLoreto, 58, of Alva. “He felt we were making a huge difference. If somebody didn’t believe it and talked to him, he changed their mind.”

On March 29, 1972, Caniford’s plane, whose call sign was Spectre 13, took off for a night mission over North Vietnamese supply routes in Laos.

At about 3 a.m., Spectre 13 was attacking an enemy convoy when it was hit by a surface-to-air missile.

Spectre 13 crashed in the jungle, and the pilot of an F-4D flying low over the burning wreckage saw no sign of survivors.

Less than an hour after the crash, a Forward Air Controller arrived at the site to control search and rescue efforts.

The Caniford family received word March 30 Jimmy Caniford’s plane had been shot down.

Jimmy Caniford’s youngest sister, Shelly, was living with her parents; Diana lived three blocks away; their father was at work; their mother was at their grandmother’s house, painting the kitchen.

“The Air Force knocked at my parents’ door, and my sister knew immediately something had happened to Jimmy,” DiLoreto said. “She called me to get our grandmother’s address. I was still sleepy and didn’t ask why.

“Then she called back. She was crying hysterically and said Jimmy’s plane had been shot down. I flew out of bed, dressed in about a minute and ran to the house.”

By 6 p.m. March 30, none of the Spectre 13 crew had been found, and the search was called off. All 14 crewmen were listed as missing in action.

“Days turned into weeks, weeks into months, months into years, and years into decades,” DiLoreto said. “You live with hope. You rely on your faith. Every day you still carry a glimmer of hope. Without it, you’re letting your brother down. When we were told they’d found Jimmy, it was: OK, we can blow out that light.”

Before the Canifords could blow out the light, however, they endured 36 years of uncertainty.

Seven years after Spectre 13 was shot down, Jimmy Caniford was officially pronounced dead and his name went up on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C.

In February 1986, a team from the United States and Laos excavated the crash site and recovered remains of nine crewmen, none of them Caniford’s.

“Mom got sick after Jimmy was shot down; her health deteriorated,” DiLoreto said. “She said the only way she could live with this is to pray he died rather than being a prisoner. But the next day, she’d say if he’s a prisoner, he might get out. It was constant turmoil. You have to live with it. You have to find a way to cope.”

Finally, on March 18, the Canifords received word a recent excavation of Spectre 13’s crash site had recovered Jimmy Caniford’s remains.

“I always thought it would be nice if we had a place to put flowers on a grave,” DiLoreto said. “I really didn’t think this would happen in my parents’ lifetime. I thought he’d greet them in heaven or something.”

Although Jimmy Caniford’s remains have been recovered, and his family can now use the overworked expression “closure,” they still feel the turmoil and will always grieve for the young man who would have been 60 in August.

“Growing up, Jimmy was my best friend,” DiLoreto said. “He was a great brother and a great man. He would have been a great father.

“If he had a dollar in his pocket, he bought you something. He was very unselfish. Obviously he was unselfish: He gave his life for what he believed.”

Eight days short of 36 years, a missing American soldier was finally found.

The remains of the last American airman of the 14-man crew or the U.S. Air Force AC-130 Aircraft 044 were found in Laos by an Army search and recovery team. The plane was downed during the Vietnam War by a surface-to-air (SAM) missile.

Enough material was found to confirm the identity of U.S. Air Force Staff Sgt. James Kenneth Caniford.

Caniford will be honored during a ceremony to be held around Memorial Day at Arlington National Cemetery.

Union County Sheriff John Schrawder, a crew chief on an AC-130, Aircraft 0571, will attend the ceremony in honor of Aircraft 044’s crew chief Tom Combs of Seattle, Washington, who is unable to attend.

Schrawder and Combs, whose airplanes were both part of an outfit called “Spectre,” lost contact for many years before becoming reacquainted through a Spectre Web site.

“I put in a search looking for my roommate and I found five of the guys I had been stationed with,” Schrawder said. “We talk just about every day on the Internet. Even if it’s just sending a joke through e-mail.”

Schrawder said he began his adult life with the men he was stationed with from 1971 to 1972 in Ubon, Thailand, and is thankful to be able to once again have contact with some of them.

“I was 19,” Schrawder said. “For more than 30 years, I had no contact with the guys I served with. There were about eight of us who were really close. I guess as you grow older and mature a little bit, you begin to miss some of the people you spent time with and have lost contact with.”

On the night of May 29, 1972, Comb’s aircraft was shot down while on a mission to stop the flow of supplies on the Ho Chi Minh Trail. All 14 crew members, including Caniford, perished.

A day later, Schrawder’s plane was shot down. Schrawder had just come off a 12-hour shift and was in bed when he heard news of his plane being downed. Fortunately, all his crew members were able to jump from the plane before it crashed and were eventually rescued in the jungle.

“When our airplanes got shot down a day apart, we (Combs) became closer,” Schrawder said. “He e-mailed me and asked if I could attend the service for Caniford, and I volunteered to go in his honor.”

Caniford’s parents, who now live in Fort Myers, Florida, and his sister, will be attending the service.

“I’m anxious to go and do my part for a friend and fellow serviceman,” Schrawder said. “It will provide some closure for the family.”

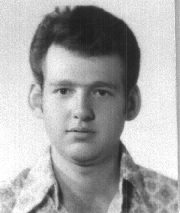

When the decades of not knowing finally ended, Jimmy Caniford’s photo sat in its usual spot on a shelf opposite his parents’ living room sofa – a portrait of the warrior, forever 23 and fighting the Vietnam War.

In the picture, Caniford strikes a pose brimming with machismo. His flight helmet is tucked under his left arm; his right arm dangles close to a pistol on his hip. Tall, handsome and jug-eared, he eyes the camera as if he’s about to swagger out of the frame.

The man in the picture bears little resemblance to the baby-faced 17-year-old who joined the Air Force in 1966, fresh out of Middletown High near Frederick, and then re-upped despite the worsening war. “This is what I do,” he told his father.

To the end he remained a jokester. A month before he vanished, he’d affected cool nonchalance in a letter home, despite writing from the world’s hottest fire zone. “Hi!” he wrote, “That’s about all I can think of right now to say.”

In March 1972, not long after that photo was snapped, a North Vietnamese missile blew his plane out of the night sky over the jungle in Laos, near the Vietnam border. All 14 crew members, it appeared, perished.

But Jimmy’s body was never found, and with no body, James Caniford was not willing to close the book on his son. And why should he concede to the most grievous loss a man can endure if there was any chance at all that Jimmy had survived?

Of course, his insistence on clinging to some long-shot hope only forced on him another anguish, namely, not knowing what had happened to his only son. Had he been captured? Tortured? Brainwashed? Later killed at the enemy’s hands?

As the years rolled by – as family members aged, moved, changed jobs, retired, got sick, saw the country embark on three new wars – he worried more and more that he’d go to his grave without the knowledge he craved.

On March 20, everything changed. The Air Force called to report that Jimmy Caniford was no longer missing in action. Remains recently unearthed at the crash site had been identified as his. Finally, on Wednesday, Jimmy will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

In an instant, the discovery seemed to clear the ambiguity that had hung over those close to Jimmy. It also extinguished – or seemed to – the hope that had flickered, if dimly, all these years.

What’s left of the 6-foot-5 airman is not a skeleton, or part of one, only the merest residue of a man. All that the Air Force could locate of Jimmy was a maxillary first molar from the upper right side of his mouth. After 36 years, a single tooth has emerged from the ground.

The question for those left behind was whether it was enough to give them certainty.

Night in 1972

As soon as Staff Sgt. Ken Felty heard that Caniford’s plane had not made it back to the airbase at Ubon, Thailand, he did something he’d never done. He chugged 8 ounces of whiskey straight, then chased it with 8 more ounces of vodka.

Hours later, he woke to the shrieks of the Thai woman cleaning the barracks, who’d found him passed out on the floor and assumed he was dead.

Felty and Caniford were not buddies; they barely knew each other. But what occurred in the wee hours on March 29, 1972, had nothing to do with friendship, just happenstance.

Caniford and Felty had the same job on different AC-130 gunships. They were known as “illuminator operators.” While others on the plane used sophisticated sensors to search for targets on the ground, the IO lay on his belly partway over an open hatch at the rear of the plane and scanned for enemy fire. If he saw danger he’d warn the pilot through a headset.

Lumbering along at 250 miles an hour, the ungainly, four-engine gunships made fat targets, all the more so because of their steady orbiting. For that reason, they flew night missions with F4 fighter jet escorts.

Felty and Caniford were flying on runs over Laos, which the American military had begun secretly bombing in 1964. Their aim was to sever the Ho Chi Minh Trail, a path snaking from Vietnam into Laos and back into Vietnam, which communist forces used to move men and arms south.

By 1972, the Americans still had not managed to shut down the trail despite the most intense bombing in history.

That March evening at Ubon, Felty was munching a hot dog in the flight line when Caniford joined him. They chatted before heading to their respective planes for another harrowing night. Lately their missions had grown increasingly dangerous as the North Vietnamese had bolstered their air defenses.

Shortly after takeoff, Felty’s gunship developed a glitch with the radar-detection device it used to locate missile launchers. With that malfunction, it was deemed too dangerous to send Felty’s AC-130 into the heavily defended sector where it had been sent to patrol. Commanders at Ubon diverted it to a less fortified sector, switching its mission with that of Spectre 13.

The IO in Spectre 13 was Jimmy Caniford.

Hours later, Felty’s crew heard over the radio that an AC-130 had gone down about 3 a.m. Only after landing did Felty learn which one.

March 1972

“Inspector Caniford,” boomed a voice over the intercom at Hoffman’s, a Hagerstown slaughterhouse, “please report to the front office.”

Jim Caniford, the 47-year-old father of the young airman, thought that was odd. State meat inspectors were rarely summoned in the middle of a shift.

It was late March 1972, and he was on the kill floor, thick with cow carcasses hung from hooks.

Off came his yellow rubber apron, white helmet and the belt he wore to carry the knives he used to slice open fresh-killed beef. He rinsed his boots and scrubbed his hands before heading to the office.

At first he didn’t see them, the two Air Force officials in crisp blue uniforms. Before his mind grasped the meaning of their presence, the stilted language of officialese was upon him: “We’re here to inform you your son’s plane was shot down.”

All he felt at first was rage. “Is that all you got to tell me?” he recalls barking. “I wouldn’t want to have your damn job for all the cows in Texas.”

Just as quickly the anger disappeared. He apologized. He called his boss to send another inspector. Then he set out to find his wife and two daughters.

The official telegram that arrived from a brigadier general was typed in capital letters. “IT IS WITH DEEP PERSONAL CONCERN THAT I OFFICIALLY INFORM YOU THAT YOUR SON STAFF SERGEANT JAMES K. CANIFORD IS MISSING IN ACTION IN SOUTHERN LAOS.”

Bleak as it was, the telegram paradoxically raised hopes at the same time as dashing them. “Other aircraft in area observed fireball and crash,” it read. But it also said: “Beepers have been heard and extensive search is being conducted.”

Jimmy’s mother, Janice, did not read any ambiguity into the news. “Your son’s gone,” she flatly told her husband.

Jim didn’t argue with her but also wouldn’t accept the finality of her view. Didn’t the telegram mention beepers? Maybe some of those boys survived and were sending out distress signals. Maybe Jimmy was one of them.

A second telegram carried a grimmer note. “The organized search has been suspended as all attempts to locate and rescue him have been unsuccessful.”

Efforts would continue to determine his status. “Until then he will be listed officially as missing in action.”

Jim Caniford clung to what little optimism he could.

The missing

People disappear all the time with little to no likelihood of ever being found, alive or dead. Not only in wars. The phenomenon occurs on almost unfathomable scales in natural disasters, such as this month’s cyclone in Myanmar and the earthquake in China.

It also happens with other human-made calamities, like the attack on the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001, which left behind hundreds of surviving family members who yearned for any physical manifestation of their loved ones to be found in the rubble. That is why the excavation of Ground Zero became akin to a sacred rite.

University of Minnesota psychologist Pauline Boss coined the term “ambiguous loss” to describe occurrences when survivors are left without any trace of a death. Mourners, she says, have always had an almost primitive need to have a body, something to see, possibly hold, to accept the death as real. In cases where that isn’t possible, she says, survivors must grapple with an anguishing ambiguity, the pairing of two opposing ideas: He’s dead, but maybe not.

That paradox describes how the Canifords reacted to Jimmy’s disappearance. Of the four, only Janice accepted that Jimmy was dead, and it gave her peace. She found solace in the fact that he had voluntarily served the Air Force and died; even as dementia began to cloud her mind in recent years, it comforted her to know he had been doing what he loved.

Jimmy’s sister, Diana, had dreamt a few months after the plane’s downing that her brother visited her and promised that he was dead and not suffering.

Yet she continued to believe he might have survived the fireball in Laos. She spun scenarios that he was living with a pretty wife in the jungle or somehow made it to the U.S. befogged by amnesia. Seeing a tall man in line at Disney World made her wonder, could that be Jimmy?

Not having hope, she felt, would be a betrayal so long as no one had physical evidence to the contrary. Whenever someone asked if she had siblings, she would say, “I have a brother who’s missing.”

Have, not had.

One of her worst days came on an autumn afternoon in 1978 when her family held a memorial service for her brother at All Saints’ Episcopal Church in Frederick after the Air Force changed his status from missing to presumed killed, a switch that opened the door for survivors’ benefits. (He also was promoted to Senior Master Sergeant.)

Diana cried her way through the service, as did her younger sister, Shelly. Diana, 11 months Jimmy’s junior, saw him as a near-twin. They’d smoked their first cigarettes together. As kids, they would play house one minute, then roll toy trucks through the mud. Shelly, just 12 when he joined the service, had flirted with the peaceniks but, when it came to her big brother, she had gauzy notions of a hero.

Sitting in the front pew, the sisters held hands as the pastor gave a talk infused with the belief that Caniford was in heaven. Before the capacity crowd, he said Caniford had come to him in a dream and uttered this: “Tell my family that wherever they are, I will be with them.”

Diana was outraged. She was convinced the pastor had made up the story. But worse, who was he to pronounce Jimmy dead?

She saw her father struggle with what to think. He knew the chance of Jimmy’s survival were negligible. But he also believed the myth that French prisoners stumbled out of Vietnamese jungles 30 years after the French pullout in the 1950s.

And he had heard rumors about two men being dragged alive from the Spectre 13 crash site as prisoners. It was a fate he thought possibly worse than death. On the other hand, it could mean his son was alive.

This is how the elder Caniford would explain his mindset: “When a plane goes into the ground and digs that deep a hole, there’s a very slight chance any of them survived that crash. But there’s always a slight chance. It’s not false hope. It’s just that you didn’t give up hope.”

All the Canifords eventually left Western Maryland, where family roots ran deep, for Florida. Diana went first, pointing her VW Bug to a sunny place free of any association with her brother. Shelly joined her, followed by Jim and Janice.

In the 1980s, Jim Caniford and Shelly attended meetings of the National League of Families, a group that did not accept the notion – firmly held by the Pentagon today – that the last American prisoners were let go by the Vietnamese in 1973.

Shelly felt cheated at having lost her brother so young. Looking back, she thinks her anger over his loss played some part in her “kamikaze” romantic relationships and even the fact that she, like her sister, never had children.

In 1986, a year after the U.S. signed a cooperation agreement with Laos, an American military team excavated the crash site. DNA testing was still years off, so forensic experts relied on dental records. Nine of the 14 crew members were identified after that dig.

But not Caniford. In a sense, nothing had changed for his sisters and their father. Jimmy still hadn’t been found. Until he was, there was hope.

Summer 2002

In the summer of 2002, Ken Felty sat at his home computer in Marion, Indiana, surfing the Internet for Web sites about American service members missing from the Vietnam War.

After many years avoiding mention of the war, he found himself interested in Vietnam again – especially the fates of Vietnam-era MIAs. (The U.S. government says that of 2,646 Americans missing as of 1973, remains of 885 have been repatriated.)

One MIA in particular haunted him: Jimmy Caniford. On this particular day, Felty came across Caniford’s name on a Web site. But for some reason a green logo began to replicate wildly, blanketing the computer screen.

Felty, by then 56 and burlier than in his Vietnam days, managed to find what he assumed was an e-mail prompt for the Webmaster and sent a message explaining the problem.

When he got a reply, the identity of the sender floored him. It was from Jim Caniford, father of his old Air Force colleague. Felty had unwittingly clicked on the spot on the computer screen where the elder Caniford had posted a memorial message about Jimmy.

The coincidence stunned Felty, and terrified him.

For years, Felty had brooded about Jimmy Caniford. Because of the last-minute switch of mission assignments, he’d always felt guilty about Jimmy. That should have been me, a voice in his head told him. Should have been my plane. He had nightmares. He would fall into periodic funks. The moroseness eventually would pass – but it would always return.

Now came a message from Jimmy’s father. How would he react if he knew the guy he was communicating with should have been the one to die rather than his son?

Eventually, though, he decided the elder Caniford should know the truth. He began telling his story over the computer and finished it in a phone call that lasted over an hour.

Caniford responded with total absolution. “It’s the luck of the draw,” he told the younger man.

He relayed his experience from World War II when he was an assistant tank driver in the Philippines. One day, his tank passed a broken-down U.S. tank sitting to the side of the road. Someone, not he, decided to forge ahead. That night Japanese soldiers killed the Americans hunkered in the disabled tank. If his tank had stopped to help, he told Felty, maybe those men would have survived.

The two men began corresponding. It did not take Felty long to discover the father’s doubts about whether Jimmy was actually dead. It’s something Felty had thought about a lot himself.

‘Good news’

The call March 20 came out of nowhere.

“Mr. Caniford,” said Art Navarro of the Air Force Mortuary Affairs office in Texas, “I have good news.”

Jim Caniford knew Mortuary Affairs’ duties included updating families on any progress in the MIA search. He also knew the military had planned to return once more to the crash site in Laos. But he had no idea that the latest dig had occurred.

Navarro told him investigators in late 2006 had discovered and subsequently identified remains of four more of the 14 crew members, using dental records and DNA from bone fragments.

Jimmy, he said, had been found.

Exhilarated, Caniford called Shelly, who called Diana. Caniford made sure to send Ken Felty an e-mail as well.

Shelly, now 54 and living in Boca Raton, Fla., with her husband, cried, but with relief. “I’m thrilled with the news, so grateful,” she said later. “It’s comforting. I know Jimmy has been at peace all this time.” She now knew that her brother’s end had been mercifully brief.

Diana, 58, got the call while walking her dog across her property north of Fort Myers. She made it to the garage before the sobs forced her to lean against a car. Her husband came running. She welcomed the discovery. Finally her aging father, now into his 80s, would know.

But at the same time, she felt a twinge of disappointment as though a light had gone out.

“You’ve lost something you’ve lived with for 36 years,” she said. “It was the hope. You make it part of your life – I have a brother.”

Felty received Caniford’s e-mail while driving cross country. He read the message on his laptop and said aloud, “Finally, the nightmare is over.”

But when he learned that Jimmy’s remains consisted of a single tooth, he was not so sure. What did that prove? Maybe Jimmy Caniford had grabbed a parachute and bailed just before the missile hit, banging his head and knocking a tooth out. Of all 14 crew members, Jimmy would have been closest to the open hatch and had the best chance of making it. The Pentagon says two men on another AC-130 did safely parachute. Who’s to say Jimmy didn’t pull off the same escape?

No parachutes were seen by the F4 pilot when Spectre 13 went down, but Felty knew the sky would have been pitch black.

“I’d say the chances are darn good he’s dead,” he said in a raspy voice. “But just like when you’re in a jury trial, you have to be beyond reasonable doubt. Me, I got reasonable doubt.”

Jim Caniford understands, but no doubts haunt him any longer. That single tooth provides him the resolution he needed, even if it means accepting, with finality, that his boy is really dead. He will be glad to see the MIA marker at Arlington National Cemetery replaced by a gravestone and the obelisk at Frederick’s Vietnam Memorial amended to indicate that Jimmy’s been found.

Two months ago, Navarro visited him and Janice at their white stucco condominium in Fort Myers. Birds chirped and palm trees swayed in the breeze when the military mortician arrived bearing a thick report on Spectre 13.

They gathered at the dining room table. Jim asked most of the questions. Both parents leaned in to see the before-and-after X-rays of the tooth and marveled at the identical topography of the filling. Neither shed a tear.

Jim told Navarro how tough the wait had been. “I’ve never reconciled myself to the fact that my son was gone, until I got the phone call that the remains had been found.

“This is finalization.”

But not the end. From the moment he found out, Caniford knew he would be the one to bring his son home.

So Wednesday of last week he flew to Hawaii, where the government has a mortuary lab, so he could escort the casket to Arlington for Wednesday’s funeral, complete with marching band and jet flyover.

Today, his flight east is scheduled to land at Dulles International Airport. It was there in Northern Virginia, some four decades ago, that he and his wife saw off their son on his final return to Southeast Asia. The 23-year-old had given them a Seiko watch to hold.

From the observation deck the parents had watched their son’s plane take off and gain altitude until there was nothing left to see.

36 years later, a son and brother is home at last

James and Janice Caniford grieve during the burial of their son, Jimmy, at

Arlington National Cemetery, 36 years after he was listed as missing in action by the U.S. Air Force.

On the day of his son’s burial at Arlington National Cemetery, James Caniford found comfort in the person he has leaned on for more than 60 years.

He gripped his wife’s hand as they watched their son, Air Force Master Sergeant Jimmy Caniford, be laid to rest with full military honors Wednesday. His other hand clenched a wad of tissues he used to wipe tears from his face.

It was a ceremony James and Janice Caniford have waited decades for.

In March 1972, Jimmy’s AC-130 gunship was shot down in Laos. Department of Defense archaeologists excavated the crash site several times, but found no trace of Jimmy. Then, in 2006, they discovered a tooth.

A couple of months ago, Air Force mortuary specialist Art Navarro informed Caniford that the tooth matched Jimmy’s DNA.

Jimmy would finally be coming home.

And the Canifords would finally have a place to grieve.

“I now have a place to go, other than a name on a wall,” Caniford said. “When you go to a name on a wall, it’s just one of 58,000 names that you’re looking at, and it’s your son, but he’s not really there.

“All my life, when people have died, there’s been a funeral and a graveyard and a stone. And I guess in my mind, this is what I needed in order to know that my son was finally laid to rest.”

Diane DiLoreto, one of Jimmy’s sisters, has said all she ever wanted to do was place flowers on her brother’s grave. Now she can do that — at gravesite 10 in section 60 at Arlington.

Jimmy joined the Air Force shortly after graduating from Middletown High School in 1966. His father still wonders whether Jimmy would be alive if he hadn’t signed the papers authorizing him to enlist.

“Airplanes was all this kid ever talked about … I couldn’t stand in front of my son’s dream,” Caniford said.

Jimmy’s dream of flying began when he got his first haircut and a barber calmed him down by pretending the clippers were a plane. His friends and family still talk of his patriotism and how he died doing what he loved most.

Others are also grateful for Jimmy’s service.

During Wednesday’s ceremony, a veteran airman approached Caniford and said he had flown with Jimmy. Caniford said the airman told him Jimmy must have saved his life more than 100 times.

Caniford said his son always had a way with people — he had tons of friends and girlfriends and would sometimes get into trouble, though it was always playful.

One time, Jimmy went fishing in a pond near Baker Park in Frederick and returned dragging a large carp that he expected Janice to cook for dinner. The carp never made it to the Canifords’ table.

“I had a great relationship with Jimmy,” Caniford said. “I had something with him …”

Shelly Caniford, Jimmy’s younger sister, said for years the family needed the closure brought by Wednesday’s ceremony.

“I never ever thought we’d find out what happened to Jimmy,” she said. “Honestly, we thought that Jimmy was taken prisoner and that was all we could think since they never found anything of Jimmy until recently … We’re very grateful to everyone who’s done what they’ve done to bring him home.”

Seeing his son’s casket after 36 years was overwhelming, James Caniford said.

“A couple of times I lost it. I just couldn’t believe that was my son in that casket,” he said. “I knew it was, but then again … it was the stark reality of knowing that this was the finality.

“When the father did the closing prayer that I remember from (when I was) a kid, it just knocked me for a loop.”

Caniford said now that Jimmy has been laid to rest, he is filled with mixed emotions, including one that he’s a bit ashamed of — relief. He no longer has to wonder where his son is, but that doesn’t change the depth of his love.

“He’s not going to be forgotten,” Caniford said. “Dear God, he won’t be forgotten.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard