Director, Central Intelligence Agency

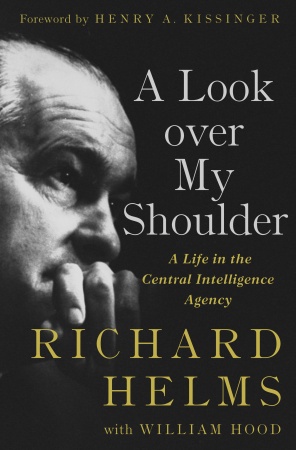

A LOOK OVER MY SHOULDER

A Life in the Central Intelligence Agency.

By Richard Helms with William Hood.

Illustrated. 478 pp. New York: Random House. $35.

Has Richard Helms, the famously closemouthed director of central intelligence — called ”the man who kept the secrets” in the apt title of Thomas Powers’s biography — finally decided to spill all? Almost, but selectively, judiciously and, it turns out, posthumously (he died last year). One of Helms’s best-kept secrets is that he was writing this autobiography, with his C.I.A. colleague William Hood, after fending off writers who had tried unsuccessfully for years to pry loose his story. Helms finally broke his silence, he tells us in ”A Look Over My Shoulder,” because the end of the cold war freed him from his self-imposed omerta.

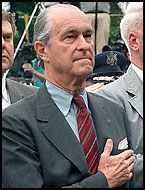

In his six and a half years leading the C.I.A., he became the very model of a modern major spymaster — urbane, impeccably attired, affable yet impenetrable, a man who could charm and chill in the same one-minute cycle. His early life reads like a pre-spook course: born on Philadelphia’s Main Line, educated at the same Swiss prep school attended by the future shah of Iran, early fluency in French and German, a magna cum laude scholar at Williams College, a first job as a reporter in prewar Europe, during which time, at the age of 23, he had an interview with Hitler.

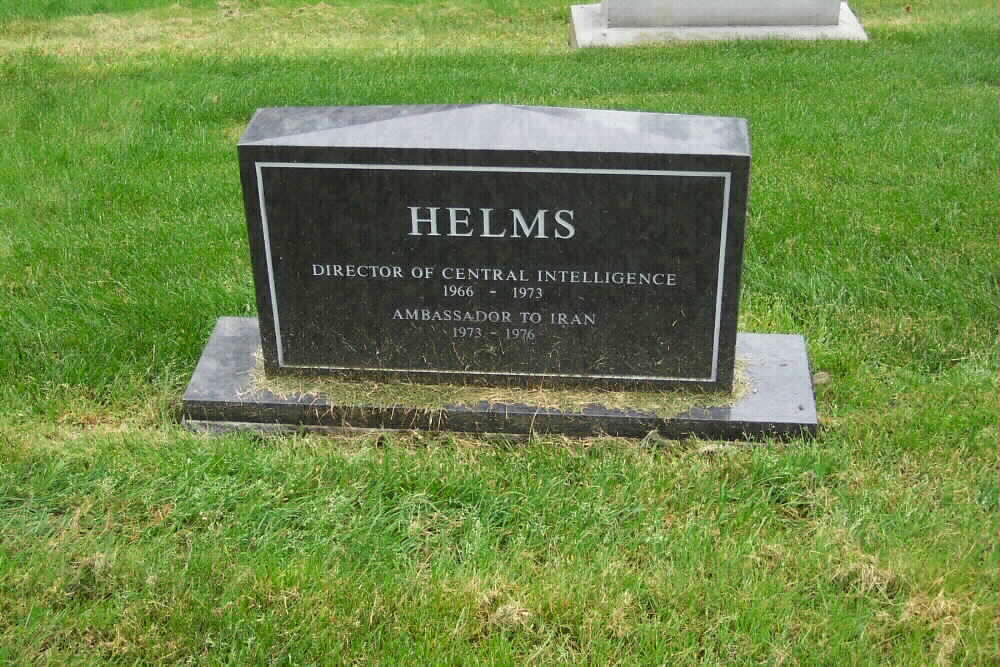

Helms was briefly diverted from his true path by a desire to make money, and thus became an unlikely advertising salesman for The Indianapolis Times. World War II got him back on track. Helms went into the Navy and then into the Office of Strategic Services, parent of today’s Central Intelligence Agency. When the war ended, ”I was hooked on intelligence,” Helms confesses. He was present at the creation and never left, pursuing a 30-year career that culminated in his rise to director of central intelligence from 1966 to 1973.

The reader is irresistibly drawn first to the two most incendiary events in that career, Watergate and Chile, the high and low, as it were. President Nixon’s attempt to insulate his administration from Watergate by enmeshing the C.I.A. was brazen even by Nixonian standards. First, Nixon’s strong-arm man, H. R. Haldeman, threatened that any C.I.A. investigation of Watergate would expose sensitive agency operations, particularly the Bay of Pigs fiasco in Cuba of 11 years before. Helms responded, ”The Bay of Pigs hasn’t got a damned thing to do with this.” More brazen still, Nixon had his counsel, John Dean, order the C.I.A. to come up with bail money to spring the jailed Watergate burglars. Helms writes, ”I had no intention of supplying any such money, or of asking Congress for permission to dip into funds earmarked for secret intelligence purposes to provide bail for a band of political bunglers.” Nixon backed down. Three cheers for Helms this time.

However, on the Chilean affair, Helms emerges as rather less sterling. He states at first that C.I.A. secret operations in Chile were designed solely ”to preserve the democratic constitutional system.” Yet in 1970, when the leftist candidate, Salvador Allende, was democratically elected president, Nixon ordered Helms to do whatever it took, with a free hand to spend $10 million, to see that Allende never took office. Nixon warned Helms to reveal nothing of this plotting even to the secretary of state, secretary of defense or United States ambassador to Chile.

This time Helms knuckled under to presidential pressure, which was eventually to produce the great trauma of his career. In February 1973, seven months before Allende was overthrown by a right-wing coup in which he died, Helms testified under oath before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that the C.I.A. had never aided Allende’s opponents. Soon after, he testified before a Senate subcommittee headed by Senator Frank Church that the C.I.A. had had no dealings with the Chilean military. These untruths would lead, in 1977, to Helms’s plea of no contest on two misdemeanor counts, resulting in a fine of $2,000 and a two-year suspended prison sentence.

Helms’s willingness to take the heat reflects a core difference between the ordinary American’s conception of citizenship and the culture inculcated by the C.I.A. Helms had long ago sworn to keep the agency’s secrets. He had also sworn before the Senate committees to tell the truth. To Helms, exposing sources and methods to headline-hunting senators ranked well below his vow to keep secrets upon which, in his judgment, the security of the nation hung. Helms claimed to wear his conviction for misleading Congress like a badge of honor. The intelligence fraternity concurred, giving him a standing ovation at a lunch after the trial and passing the hat to cover his fine.

Tales of derring-do enliven Helms’s readable story throughout, but its real significance is likely to surprise spy-thriller aficionados and conspiracy theorists: the C.I.A. is, first and foremost, simply a government agency. No differently than the Department of Agriculture, it executes White House policy. Helms’s professional life is essentially the story of undercover operations ordered by presidents. Standout examples: Eisenhower’s decisions to topple Prime Ministers Patrice Lumumba in Congo and Mohammed Mossadegh in Iran, President Jacobo Arbenz in Guatemala and Fidel Castro in Cuba (continued by Kennedy), and Nixon’s clandestine war against Allende. In the 1960’s, at the peak of racial upheaval and demonstrations against the Vietnam War, President Johnson ordered Helms ”to track down the foreign Communists who are behind this intolerable interference in our domestic affairs.” This demand led Helms to start up a covert snooping operation that he admits involved ”a violation of our charter” not to spy on Americans at home.

On the big stuff, Helms makes a convincing case that rather than being a ”rogue elephant,” an ”invisible government” as often charged, the C.I.A. is a president’s political weapon of last resort, the keeper of the bag of dirty tricks. If agency acts appear roguish, Helms says, it is when government policy is roguish. He describes the dilemma when a president orders his intelligence chief to step out of bounds: ”What is the D.C.I. to do? . . . Has he the authority to refuse to accept a questionable order on a foreign policy question of obvious national importance?” At this point, the spy chief’s choices are to sign on or resign.

Helms offers telling instances of the uselessness of even the keenest intelligence if its message is unwelcome at the top. In analyzing the domino theory, which held that if Vietnam fell, the whole non-Communist world would teeter, Helms sent Johnson a secret assessment that concluded, ”The net effects would probably not be permanently damaging to this country’s ability to play its role as a world power.” Johnson ignored the report’s existence and pressed on with the war. During the cold war debate over the Soviet Union’s capacity to deliver a first-strike knockout punch to the United States, the C.I.A. found that the Kremlin had neither the intention nor the weaponry to do so. The Nixon administration told Helms, in effect, to get on the team or shut up.

Dick Helms remained throughout his career a thoroughgoing company man, albeit with spine-tingling job descriptions. His loyalty to old C.I.A. hands could be uncritical. The most egregious example involved his counterintelligence chief, James Jesus Angleton. The paranoid Angleton practically paralyzed the C.I.A.’s Soviet division by a long, fruitless hunt for a mole inside the agency. Over a hundred loyal officers fell under investigation; some were forced to resign. In implementing the dismissals, Helms says, ”I had no choice but to accept a decision that in effect said each was innocent, but that the innocence could not be proved.”

In this post-9/11 age of anxiety one looks for lessons in the life of a man who spent his career in the intelligence end of national security. The lesson here is how totally changed the present amorphous threats are from the comparatively clear-cut cold war battles Helms fought for a generation. By the time he died at the age of 89, with those battles long behind him, Helms’s blemishes had been washed away. In 1983 President Reagan awarded him the National Security Medal. Upon his death he was buried with full honors in Arlington National Cemetery.

Whether one likes or loathes the furtive world in which Helms lived, whether one sees him as a patriot or compliant careerist, this surprise autobiography provides an unsurpassed insider look into how American intelligence actually operates. It’s a view offering more than enough ammunition for admirers and antagonists alike.

Joseph E. Persico’s latest book is ”Roosevelt’s Secret War: FDR and World War II Espionage.”

A LOOK OVER MY SHOULDER

A Life in the Central Intelligence Agency

By Richard Helms with William Hood

Random House. 478 pp. $35

Richard Helms was back among friends. On a crisp and tranquil late November morning, tinged with the musty scent of dried leaves and old bark, the man who was arguably America’s most famous spy since Nathan Hale descended into eternal darkness. Buried with him, beneath a gently sloping hill at Arlington National Cemetery, was a lifetime of mystery, secrets and controversy. Nearby, sharing the same hallowed ground, were the graves of his old friend Frank Wisner, a specialist in covert action, and General Walter Bedell Smith, a mentor and fellow former director of the Central Intelligence Agency.

But before he made his final exit last year at the age of 89, Helms left behind a packet of long-held secrets, like a spy loading a dead drop and then disappearing into the cold. They are contained not in a moldy tree trunk but in his posthumous autobiography, A Look Over My Shoulder.

Over the years, I occasionally shared a meal with the legendary spymaster at one of his favorite haunts, Washington’s Sulgrave Club, where his wife, Cynthia, was a member. Tall and lanky, with thin lips pursed together as if sealed with a zipper, he once told me that he had always vowed never to write about his life in the shadows. He even refused to read books he perceived as biased against him or the agency, such as Thomas Powers’s well-received The Man Who Kept the Secrets, published in 1979. Then, while on vacation once during the mid-1990s, he brought along Powers’s book and finally began turning the pages. Pleasantly surprised by the author’s accuracy and fairness, he gradually made the decision to at last unseal a bit of his cipher-locked past.

It is too bad he did not make the decision much earlier, when many of the words, the events, the emotions, the colors and the details would still have been fresh in his mind. Writing at such a long remove in time is a little like looking through the wrong end of a telescope. Compounding his difficulty was the lack of access to still-classified documents and a rigid agency review process. The result is a book with too much flat history and too few new insights and revelations. Nevertheless, the opportunity to at last see much of the 20th century through Helms’s probing eyes is well worth the price.

While offering few new details in recounting some of the major events of his long tenure at the CIA — he saw no indications of conspiracy during the Kennedy assassination, for example — Helms sometimes does come up with surprises. One involves the deadly Israeli attack on the American electronic surveillance ship USS Liberty during the Six Day War in 1967. Thirty-four American sailors were killed, and 171 were wounded in the incident. Although at the time Israel claimed it was a mistake, and an “interim” CIA intelligence memorandum agreed, that view later changed. “I had no role in the board of inquiry that followed,” Helms writes, “or the board’s finding that there could be no doubt that the Israelis knew exactly what they were doing in attacking the Liberty. I have yet to understand why it was felt necessary to attack this ship or who ordered the attack.” This is consistent with the views of some members of the administration at the time, including Secretary of State Dean Rusk and the director and deputy directors of the National Security Agency, which was in charge of the ship.

Overshadowing all else during Helms’s years as director were the Vietnam War and the domestic protests it spawned. Among the operations Helms was most proud of was the CIA’s very secret paramilitary role in Laos, attempting to resist a government takeover by communist forces. Until America pulled out of Vietnam, the operation succeeded in fighting back the guerrillas and largely maintaining the status quo. “We had fulfilled our mission and we remain proud of it,” he writes. “We had won the war!” Vietnam, however, was a different story.

But it was the war at home that long haunted Helms. “Nothing in my thirty-year service brought me more criticism,” he wrote, “than my response to President Johnson’s insistence that the Agency supply him proof that foreign agents and funds were at the root of the racial and political unrest that took fire in the summer of 1967.” The agency’s response was given the apt cryptonym CHAOS. “CHAOS,” he admits, “was my responsibility.” In the process of giving Johnson the answer he was not expecting — there was “no trace” of foreign involvement — the agency for the first time began secretly treading on domestic soil, “a violation of our charter,” Helms confesses.

If Helms is remembered for the controversy of CHAOS, he should also be remembered for the courage of standing up to President Nixon’s attempt to tar the CIA with the brush of Watergate. Shortly after the break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters and the arrest of those involved, Nixon had his White House lawyer, John Dean, put pressure on Helms’s deputy, Vernon Walters. “Dean had one request,” Helms writes. “The White House wanted money from CIA to make bail for the burglars.” Helms refused, telling Walters, “There was no way that the [CIA] could furnish secret funds to the Watergate crowd without permanently damaging and perhaps even destroying the Agency.” Five months later, Helms got the boot.

If Helms thought that he was finally out of harm’s way once he turned in his cloak and dagger, he couldn’t have been more mistaken. Nominated to become ambassador to Iran, he was called before an open Senate committee for confirmation and was asked whether the CIA played a role in a coup in Chile that brought down the government of Salvador Allende. Rather than tell the truth and expose the CIA’s involvement or ask to answer the question in closed session, Helms simply lied and said no.

Years later the answer came back to haunt him. He was charged with failing to testify “fully and completely” before the committee and pleaded no contest. Following a sharp tongue-lashing by the judge, who told Helms he stood before the court “in disgrace and shame,” he was sentenced to two years in prison and a $2,000 fine. The judge then suspended the jail time. Helms turned ashen. But upon leaving the courthouse he claimed that the conviction represented a “badge of honor” for having lied to protect an agency operation. Six years later, he received the National Security Medal, the highest award in the intelligence community, from President Ronald Reagan for “exceptional meritorious service.”

As the horse-drawn caisson waited to carry Richard Helms to his final resting place on that chilly fall morning, the man who must now keep the secrets paid tribute. “Wherever American intelligence officers strive to defend and extend freedom,” said George Tenet, the director of Central Intelligence, “Richard Helms will be there.” •

James Bamford is the author, most recently, of “Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency.”

From contemporary press reports:

Buried with military honors, former CIA Director Richard Helms was remembered on Wednesday as a man “who knew the value of a stolen secret” and became one of the great heroes of America’s clandestine intelligence operations.

“In Richard Helms, intelligence in service to liberty found an unsurpassed champion,” said George Tenet, the CIA’s current director.

Helms, who died at 89 on October 23, 2002, began his intelligence career during World War II and rose through the ranks during the Cold War. He served as CIA director for six years before President Nixon fired him for refusing to block an FBI probe into the 1972 Watergate break in.

He was buried at Arlington National Cemetery before a large group of mourners that included members of the intelligence and defense establishments of several presidential administrations. At a memorial service at Fort Myer, Virginia, following Helms’ burial, Tenet called Helms “one of our greatest heroes.”

“He came to know, as few others ever would, the value of a stolen secret, and the advantage that comes to our democracy from the fullest possible knowledge of those abroad determined to destroy it,” Tenet said.

Beginning in the 1930s as an enterprising reporter for United Press, for whom he interviewed Adolf Hitler, Helms found his way to wartime service with the Office of Strategic Services, the U.S. intelligence agency that was the forerunner of the CIA.

At the OSS, Tenet said, “Richard Helms found the calling of his lifetime.”

“In its Secret Intelligence Branch, he mastered the delicate, demanding craft of agent operations,” Tenet said. “He excelled at both the meticulous planning and the bold vision and action that were — and remain today __ the heart of our work to obtain information critical to the safety and security of the United States __ information that can be gained only through stealth and courage.”

Tenet called Helms’ later CIA career “the stuff of legend,” praising his “sound operational judgment, his complete command of facts (and) his reputation as the best drafter of cables anywhere …”

“In an organization where risk and pressure are as common as a cup of coffee, he was unflappable,” Tenet said.

Tenet said Helms’ legacy is the American intelligence agents he taught and who carry on in his place. Helms himself addressed the profession of an intelligence officer in a 1996 speech quoted in the program for his memorial service.

“Military conflicts and terrorist attacks have not gone out of style,” he said then. “An alert intelligence community is our first, best line of defense. Service there is its own reward.

A military honor guard escorts the horse-drawn carriage carrying the remains of former

CIA Director Richard Helms during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2002.

A U.S. Navy honor guard prepares to remove the cremated remains of former CIA Director Richard

Helms from a ceremonial flag-draped casket on a caisson at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia November 20, 2002.

Members of a naval honor guard carry a flag and a box containing the ashes of former CIA

Director Richard Helms during ceremonies at Arlington National Cemetery

CIA Director George Tenet, right, awaits the flag that draped the casket of former CIA Director Richard Helms

during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Va. Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2002.

Helms, the spymaster who led the CIA through some of its most difficult years and was later fired by

President Nixon when he refused to block an FBI probe into the Watergate scandal, died last month. Afterward,

Tenet presented the flag to Helms’ widow.

Family members of former CIA Director Richard Helms hold the flag that draped his casket

during funeral services at Arlington National Cemetery , Wednesday, Nov. 20, 2002.

Cynthia Helms, widow of former CIA Director Richard Helms, pauses over a container with

the remains of Helms during funeral services in Section 7 of Arlington National Cemetery

Former CIA Director Helms Dead at 89

Former CIA Director Richard Helms, who led the spy agency during the height of the Vietnam War and resisted attempts by President Richard Nixon to involve the CIA in Watergate, has died. He was 89.

Helms was in declining health and died at his home on Tuesday. The cause of death was not immediately available.

“The men and women of American intelligence have lost a great teacher and a true friend,” CIA Director George Tenet said in a statement on Wednesday. He ordered flags at the agency’s headquarters in Virginia flown at half-staff.

“As director of central intelligence for almost seven years, he steered a bold and daring course, one that rewarded both rigor and risk,” Tenet said.

Helms led the spy agency from June 1966 to February 1973 during one of the most contentious periods of American history with both the Vietnam War and Watergate. He was the first career CIA officer to reach the agency’s top position.

Helms was first appointed by President Lyndon Johnson and in 1969 was reappointed by Nixon.

After the controversial break-in at Democratic headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in 1972, Helms resisted attempts by Nixon to involve the CIA in the ensuing cover-up, which ultimately brought down his presidency. The CIA chief was not reappointed to his post.

Helms’ name also emerged in the guessing game of who was “Deep Throat,” the confidential source that helped Washington Post reporters break open the Watergate scandal.

After leaving the CIA, Helms went on to become U.S. ambassador to Iran from March 1973 to January 1977.

In 1977, he was charged with perjury for denying the CIA had tried to overthrow the government in Chile in testimony to Congress. Helms was given a suspended jail sentence.

‘PAINFUL PERIOD’

“I think he remembered that as a painful period in his life. Dick always believed that he was seeking a higher good there in protecting the sources who had worked with the agency at risk to themselves and our own people in the field,” said John Gannon, former National Intelligence Council chairman and friend of Helms. “History will judge his performance there.”

A CIA report released two years ago said in September 1970 Nixon told Helms that a Salvador Allende regime in Chile would not be acceptable and authorized $10 million for the CIA to prevent him from reaching power.

Allende was elected, so then the CIA was directed to instigate a coup but those efforts also failed. Three years later in September 1973, a bloody coup put Gen. Augusto Pinochet in power and Allende killed himself. The CIA has maintained it did not instigate that coup.

Helms worked for years in the CIA’s clandestine service which conducts covert operations and became deputy director for plans in 1962. During that time, the CIA tried unsuccessfully to remove President Fidel Castro from power in Cuba.

Helms, a private consultant since 1977, remained a helping hand of experience to the CIA, Gannon said. “He was almost a folk hero at CIA because he actively worked to stay engaged and to be useful and helpful to people in the agency,” he said.

Helms had a quiet, reserved manner that could intimidate subordinates and was known as a dapper dresser.

“Dick was a man you had to work to get to know. He had a certain reserve about him and he had a patrician air,” Gannon said. “But if you cut through that and got to know Dick he was an extremely warm man with a really great capacity for friendship,” he said.

Helms started out as a journalist for the predecessor to United Press International in Europe, covered the 1936 Olympic games in Berlin and interviewed German leader Adolf Hitler.

He joined the Navy in 1942 and was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor to the CIA. He worked in Washington, London, Paris and Luxembourg, running espionage operations against Germany.

Helms will be buried at Arlington National Cemetery on November 20, 2002.

Richard M. Helms, 89, the quintessential intelligence and espionage officer who joined the Central Intelligence Agency at its founding in 1947 and rose through the ranks to lead it for more than six years, died Tuesday night (23 October 2002) at his home, the CIA announced today. No immediate cause of death was reported.

Mr. Helms was the first career intelligence professional to serve as the nation’s top spymaster, and he was among the last of the remaining survivors of the CIA’s organizing cadre, operatives who earned their espionage stripes as young men during World War II.

His years at the agency covered a period in which CIA service was widely honored as a noble and romantic calling in the Cold War against the Soviet Union. But much of this mystique had dissolved in the national malaise that accompanied the war in Vietnam and the Watergate scandal. At his retirement in 1973, Mr. Helms left an organization viewed with suspicion by many and about to undergo intense scrutiny from an unfriendly Congress for activities ranging from assassination plots against foreign leaders to spying on U.S. citizens.

As a veteran of the craft of espionage, he had always followed a code that stressed maximum trust and loyalty to his agency and colleagues; maximum silence where outsiders were concerned. “The Man Who Kept the Secrets,” was the title chosen by author Thomas Powers for his biography of Mr. Helms.

In the judgment of Richard Helms, the CIA worked only for the president. He did not welcome congressional inquiry or oversight. In 1977 he pleaded no contest in a federal court to charges of failing to testify fully before Congress about the CIA role in the covert supply of money to Chilean anti Marxists in 1970 in an effort to influence a presidential election. “I found myself in a position of conflict,” Mr. Helms said. “I had sworn my oath to protect certain secrets.”

He received a suspended two-year prison sentence and a $2,000 fine, which was paid in full by retired CIA agents. Six years later at a White House ceremony, Mr. Helms received the National Security Medal from President Reagan for “exceptionally meritorious service.” He said he considered this award “an exoneration.”

His career at the CIA covered periods of searching for communists in the U.S. government and the Red Scare tactics of Sen. Joseph R. McCarthy (R-Wis.); the ill-fated CIA-sponsored Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, and plots against Cuban dictator Fidel Castro. It included the rending of the American social fabric and the antiwar protests of the Vietnam era, and it ended during the the Watergate crisis that ultimately ended the presidency of Richard M. Nixon. On leaving the CIA, Mr. Helms served three years as ambassador to Iran, then in 1976 ended his government service.

As one of its ranking officers for most of the CIA’s first 25 years, Mr. Helms helped form and shape the agency, and he recruited, trained, assigned and supervised many of its top agents. During the 1950s and early 1960s he held high positions in the division responsible for clandestine operations. ” . . . He was a kind of middle man between the field and Washington policymakers, approving and even choosing the wording of cables to the field describing ‘requirements’; and passing on concrete proposals for operations from the local CIA stations,” Powers wrote in his biography of Mr. Helms.

By 1958 he was second in command of covert operations when he was passed over for the directorship of that activity in favor of Richard M. Bissell Jr., who in 1961 would plan and direct the disastrous Bay of Pigs invasion of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. In this operation, a force of 1,200 CIA trained and equipped Cuban exiles attempted to retake the island from Castro, but the effort failed and most of the invaders were killed or captured.

Mr. Helms, who by nature had been cool and skeptical toward covert operations on such a large scale, had kept his distance from the Bay of Pigs. But the fiasco proved to be Bissell’s undoing and he retired amid the political fallout that followed. Mr. Helms replaced him in 1962, winning at last the position that had eluded him four years earlier. He became the CIA’s deputy director for plans, the innocuous sounding title of covert action chief. With his new assignment he inherited a pressure campaign from the White House to get rid of Castro by other means. During the next several months the agency would contemplate schemes for Castro’s overthrow or assassination, but none ever materialized.

In 1965 Mr. Helms was named to the number two job at the agency, deputy director of Central Intelligence. Retiring CIA chief John A. McCone had campaigned to have Mr. Helms succeed him, but President Lyndon B. Johnson instead chose Navy Vice Adm. William F. Raborn, who lasted only 14 months in the job. In 1966 the president named Mr. Helms CIA director. He would serve longer as Director of Central Intelligence than anyone except Allen Dulles, the legendary spymaster who led the CIA from 1953 to 1961.

As America’s top spymaster, Powers wrote in his biography, Mr. Helms “is remembered as an administrator, impatient with delay, excuses, self-seeking, the sour air of office politics. Asked for an example of Helms’ characteristic utterance, three of his old friends came up with the same dry phrase, ‘Let’s get on with it.’ . . . Helm’s style was cool by choice and temperment; his instinct was to soften differences, to find a middle ground, to tone down operations that were getting out of hand, to give faltering projects one more chance rather than shut them down altogether, to settle for compromise in the interests of bureaucratic peace.” He tended to work regular hours, 8:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m., and his desk was always cleared when he left the office at night.

Mr. Helms kept a low public profile as CIA director, and he avoided publicity. But he lunched occasionally with influential figures in the media, and he was assiduous in cultivating the congressional support he needed to manage his agency. He made only one public speech during his years as CIA leader, telling the nation’s newspaper editors that “the nation must, to a degree, take it on faith that we, too, are honorable men, devoted to her service.”

Richard McGarrah Helms was born in St. Davids, Pa., to a family of financial means. His father was an Alcoa executive and his maternal grandfather a leading international banker. He grew up in South Orange, N.J., and attended high school in Switzerland for two years. While there he became proficient in French and German.

In 1935 he graduated Phi Beta Kappa from Williams College, where in his senior year he was president of his class, editor of the campus newspaper and the yearbook and president of the honor society.

His life’s ambition on leaving college was to own and operate a daily newspaper. In pursuit of that goal he paid his own fare to London where he became a European reporter for United Press. His assignments included coverage of the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. The following year he was one of a group of foreign correspondents to interview Adolf Hitler.

Shortly thereafter he returned to the United States and took a job with the Indianapolis Times newspaper, where by 1939 he had become national advertising director.

With the entry of the United States into World War II he joined the Navy, and in 1943 was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, the U.S. wartime espionage agency that antedated the CIA. There he had desk jobs in New York and Washington and later in London. At the end of the war he was posted in Berlin, where he worked for Allen Dulles.

Discharged from military service in 1946, he continued doing intelligence work as a civilian. When the U.S. wartime intelligence forces merged into the CIA in 1947, Mr. Helms became one of the architects of the new organization.

During the 1950s, Dulles gave him special assignments from time to time. At the height of Sen. McCarthy’s fervid hunts for communists inside the government, Mr. Helms headed a CIA committee to protect the agency against McCarthy’s efforts to infiltrate the CIA with his own informers. The committee’s job was to monitor reports of covert approaches to CIA officers by McCarthy agents and to plug any leaks.

During the years there would be more assignments with domestic political implications. Early in Mr. Helms’ directorship, as the war in Vietnam and the antiwar protests were both escalating, Johnson asked the CIA to determine whether antiwar activity in the United States was being financially or otherwise backed by foreign countries. In response to this request, the agency in 1967 launched a domestic surveillance program known as “Operation Chaos,” which became the focus of intense controversy when it was disclosed publicly by The New York Times in 1975.

With the election of Richard Nixon as president in 1968, White House involvement with the CIA only intensified. Even before the 1972 Watergate break-in at Democratic National Committee headquarters that led to Nixon’s downfall, the White House had demanded and received CIA files on agency plots to assassinate foreign leaders during the Kennedy and Johnson administrations. These included Ngo Dinh Diem of South Vietnam, Rafael Trujillo of the Dominican Republic and Patrice Lumumba of the Congo.

But the relationship between Mr. Helms and Nixon was never smooth, and in November of 1972, shortly after he had been elected to his second term, the president summoned his CIA chief to a meeting at Camp David and asked him to resign. Nixon’s reasons were never made public, but Power said in his biography that Mr. Helms was convinced “that Nixon fired him for one reason only – because he had refused wholeheartedly to join the Watergate cover-up.”

At the Camp David meeting, the president had asked Mr. Helms if he’d like to be an ambassador, and the two men had agreed on Iran. But during his three years in Iran, Mr. Helms would make more than a dozen trips back to Washington to testify before Senate committees investigating CIA activities during his directorship.

Links between unsavory Nixon White House activities and the CIA, including the agency’s lending of disguises to Watergate conspirator E. Howard Hunt and the CIA backgrounds of many of the Watergate burglars prompted an internal examination ordered by Mr. Helm’s successor at the agency, James R. Schlesinger. This resulted in a 693-page compendium of agency misdeeds, including assassination attempts, burglaries, electronic eavesdropping and LSD testing of persons without their knowledge.

William R. Colby, who succeeded Schlesinger as director of Central Intelligence, quietly briefed House and Senate overseers on the contents of the report, which became known in the agency as “the family jewels.” The substance of the briefing did not surface publicly for two years, but it eventually did become known through a combination of press accounts, a presidential commission and congressional committees bent on public disclosure. Ultimately, the result was creation of permanent House and Senate oversight committees to monitor the CIA and all other U.S. intelligence agencies.

In 1976 Mr. Helms returned from Tehran, retired from government service and became an international consultant.

In 1939 Mr. Helms married Julia Bretzman Shields of Indianapolis. They separated in 1967 and divorced in 1968. They had one son, Dennis.

In 1968 he married Cynthia McKelvie.

Richard Helms, Ex-C.I.A. Chief, Dies at 89

Mr. Helms (left) in 1966 and (right) in 1973 with President Richard Nixon

Richard Helms, a former Director of Central Intelligence who defiantly guarded some of the darkest secrets of the cold war, died of multiple myeloma today. He was 89.

An urbane and dashing spymaster, Mr. Helms began his career with a reputation as a truth teller and became a favorite of lawmakers in the late 1960’s and early 70’s.

But he eventually ran afoul of Congressional investigators who found that he had lied or withheld information about the United States role in assassination attempts in Cuba, anti-government activities in Chile and the illegal surveillance of journalists in the United States.

Mr. Helms pleaded no contest in 1977 to two misdemeanor counts of failing to testify fully four years earlier to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. His conviction, which resulted in a suspended sentence and a $2,000 fine, became a rallying point for critics of the Central Intelligence, Agency who accused it of dirty tricks, as well as for the agency’s defenders, who hailed Mr. Helms for refusing to compromise sensitive information.

In the title of his 1979 biography of Mr. Helms, Thomas Powers called him “The Man Who Kept the Secrets” (Pocket Books). Mr. Helms’s memoir, “A Look Over My Shoulder: a Life in the C.I.A.,” is to be released in the spring by Random House.

After he left the C.I.A. in 1973, Mr. Helms served until 1977 as the American ambassador to Iran, whose ruler, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, was supported by the United States. He later became an international consultant, specializing in trade with the Middle East.

Born on March 30, 1913, in St. Davids, Pa., Richard McGarrah Helms — he avoided using the middle name — was the son of an Alcoa executive and grandson of a leading international banker, Gates McGarrah. He grew up in South Orange, N.J., and studied for two years during high school in Switzerland, where he became fluent in French and German.

At Williams College, Mr. Helms excelled as a student and a leader. He was class president, editor of the school newspaper and the yearbook, and was president of the senior honor society. He fancied a career in journalism, and went to Europe as a reporter for United Press. His biggest scoop, he said, was an exclusive interview with Hitler.

In 1939 he married Julia Bretzman Shields, and they had a son, Dennis, a lawyer in Princeton, N.J. The couple were divorced in 1968, and Mr. Helms married Cynthia McKelvie later that year. She and his son survive him.

When World War II broke out, Mr. Helms was called into service by the Naval Reserve and because of his linguistic abilities was assigned to the Office of Strategic Services, the precursor to the C.I.A. He worked in New York plotting the positions of German submarines in the western Atlantic.

From the beginning, he worked in the C.I.A.’s covert operations, or “plans” division, and by the early 1950’s he was serving as deputy to the head of clandestine services, Frank Wisner.

In that capacity, in 1955, Mr. Helms impressed his superiors by supervising the secret digging of a 500-yard tunnel from West Berlin to East Berlin to tap the main Soviet telephone lines between Moscow and East Berlin. For more than 11 months, until the tunnel was detected by the Soviet Union, the C.I.A. was able to eavesdrop on Moscow’s conversations with its agents in the puppet governments of East Germany and Poland.

Over the next 20 years, Mr. Helms rose through the agency’s ranks, and in 1966 he came the first career official to head the C.I.A. He served under such men as Allen W. Dulles, Richard M. Bissell, John A. McCone and Vice Adm. William F. Raborn.

During most of his tenure as C.I.A. chief, Mr. Helms received favorable attention from lawmakers and the press, who remarked on his professionalism, candor, and even his dark good looks.

That reputation grew after 1973, when Mr. Helms clashed with President Richard M. Nixon, who sought his help in thwarting an F.B.I. investigation into the Watergate break-in. When Mr. Helms refused, Mr. Powers wrote, Mr. Nixon forced him out and sent him to Iran as ambassador.

But Mr. Helms soon found himself called to account for his own actions when the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence delved into the agency’s efforts to assassinate world leaders or destabilize socialist governments.

The committee, which was led by Senator Frank Church, Democrat of Idaho, accused Mr. Helms of failing to inform his own superiors of efforts to kill the Cuban leader Fidel Castro, which the Senate panel called “a grave error in judgment.”

A separate inquiry by the Rockefeller Commission also faulted Mr. Helms for poor judgment for destroying documents and tape recordings that might have assisted Watergate investigators.

But the most contentious criticism of Mr. Helms centered on Chile. In testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Mr. Helms insisted that the C.I.A. had never tried to overthrow the government of President Salvador Allende Gossens or funneled money to political enemies of Mr. Allende, a Marxist.

Senate investigators later discovered that the C.I.A. had run a major secret operation in Chile that gave more than $8 million to the opponents of Mr. Allende, using the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation as a conduit. Mr. Allende was killed in a 1973 military coup, which was followed by more than 16 years of military dictatorship.

In 1977, Mr. Helms stepped down as ambassador to Iran and returned to Washington to plead no contest to charges that in 1973 he had lied to a Congressional committee about the intelligence agency’s role in bringing down the Allende government.

“I had found myself in a position of conflict,” he told a federal judge at the formal proceeding after entering a plea agreement with the Justice Department. “I had sworn my oath to protect certain secrets. I didn’t want to lie. I didn’t want to mislead the Senate. I was simply trying to find my way through a difficult situation in which I found myself.”

The judge responded, “You now stand before this court in disgrace and shame,” and sentenced him to two years in prison and a $2,000 fine. The prison term was suspended.

Mr. Helms said outside the courtroom that he wore his conviction “like a badge of honor,” and added: “I don’t feel disgraced at all. I think if I had done anything else I would have been disgraced.”

Later that day he went to a reunion of former C.I.A. colleagues, who gave him a standing, cheering ovation, then passed the hat and raised the $2,000 for his fine.

For a man who considered himself a genuine patriot, it was a bleak note on which to end his professional career. Mr. Helms believed he had performed well in a job that, although many Americans considered it sinister and undemocratic, was nevertheless a cold-blooded necessity in an era of cold war.

Mr. Helms, who was allowed to receive his government pension, put his intelligence experience to use after his retirement. He became a consultant to businesses that made investments in other countries.

He was known as a charming conversationalist, a gregarious partygoer and an accomplished dancer, and he and his wife continued to be familiar figures on the capital party scene.

STATEMENT BY DIRECTOR OF CENTRAL INTELLIGENCE

GEORGE J. TENET ON THE DEATH OF

AMBASSADOR RICHARD MCGARRAH HELMS

With the deepest sadness, I have learned of the death of Ambassador Richard Helms. My thoughts and prayers are with his family at this time of grief.

The United States has lost a great patriot. The men and women of American intelligence have lost a great teacher and a true friend.

His service to country spanned more than half a century. But his career and contributions are not simply measured in history, they changed it.

As a young Naval officer in the Second World War, Richard Helms found his place in American espionage. From that moment on, in posts of increasing responsibility, in times of conflict and in peace, he shaped the intelligence effort that has helped keep our country strong and free.

As Director of Central Intelligence for almost seven years, he steered a bold and daring course, one that rewarded both rigor and risk. Clear in thought, elegant in style, he represents to me the best of his generation and profession.

To the very end of his life, Ambassador Helms shared his time and wisdom with those who followed him in the calling of intelligence in defense of liberty. His enthusiasm for this vital work, and his concern for those who conduct it, never faltered.

I will miss his priceless counsel and his warm friendship. But the name and example of Richard Helms will be treasured forever by all who work for the safety and security of the United States.

HONORABLE RICHARD M. HELMS (Age 89)

On Wednesday, October 23, 2002. Dear husband and friend of Cynthia R. Helms at his residence in Washington, DC. Father of Dennis and grandfather of Julia and Alexander; brother of Betty Helms Hawn, Pearsael Helms and Gates Helm; stepfather of Didi Anderson, Jill McKelvie Neilsen, Roderick McKelvie, Allan McKelvie and Linsday McKelvie Eakin and step-grandfather of 15.

Service and burial at Arlington Cemetery mid-November, date and time to be announced. In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to CIA Memorial Foundation, created to provide benefits to the families of agents of the CIA killed in the line of duty, c/o Jeffrey H. Smith, Esq., Arnold & Porter, 555 12th Street, NW, Washington, DC or Community Hospices, Hospice of Washington, 4200 Wisconsin Ave, NW, Washington, DC 20016.

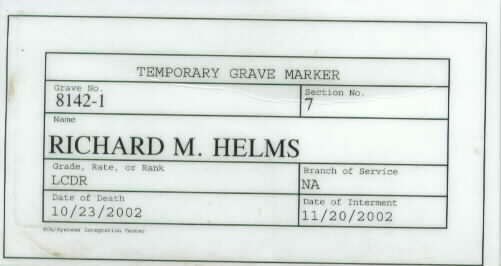

HELMS, RICHARD M

LCDR US NAVY

VETERAN SERVICE DATES: 06/20/1942 – 01/30/1945

- DATE OF BIRTH: 03/30/1913

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/23/2002

- DATE OF INTERMENT: 11/20/2002

- BURIED AT: SECTION 7 SITE 8142-1

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard