WEBMASTER MESSAGE:

Was Lieutenant Sutton the victim of a suicide, an accidental killing or a victim of murder? Read through the following stories which report on the second inquiry into the Lieutenant’s death and decide for yourself!

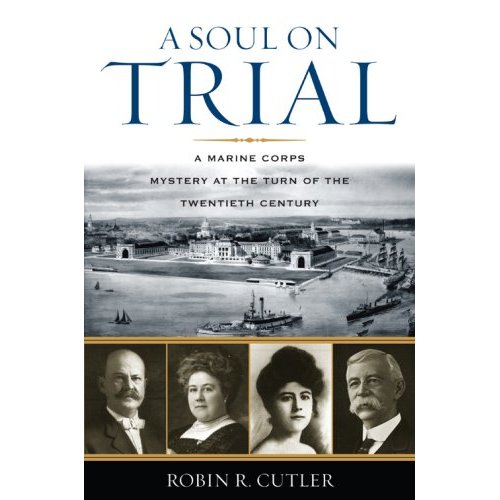

Please also note that the following items are the result of our own research and that none was contributed to, or authored by, Ms. Robin R. Cutler, whose fine new book, “Soul on Trial,” is mentioned at the bottom of this remembrance and which is now available at all book stores and at Amazon.Com. We highly recommend the book for visitors who wish to learn more about the circumstances surrounding the death of Lieutenant Sutton.

Errata:

Some of these materials were originally published in newspapers of the day across the Nation, but principally the the New York Times, The Washington Star, The Washington Post, The New York Evening Journal, The New York Evening World and the The New York Evening Post. Sadly, all but the New York Times and the Washington Post are long defunct. In our haste to post Lieutenant Sutton’s remembrance here prior to the 100th anniversary, the original remembrance failed to give proper credit to these fine publications. For this, the webmaster takes full responsibility. Without their coverage of the second Board of Inquiry, the story of Lieutenant Sutton could not have been told and we are grateful that these publications covered this thought provoking story.

LIEUTENANT SUTTON PUTS BULLET IN BRAIN

Marine Corps Officer Commits Suicide At Annapolis

He Fought To Kill Himself

Discovered About To Shoot Himself, Sutton Was Disarmed,

But He Snatched Another Revolver From Blouse And Fired

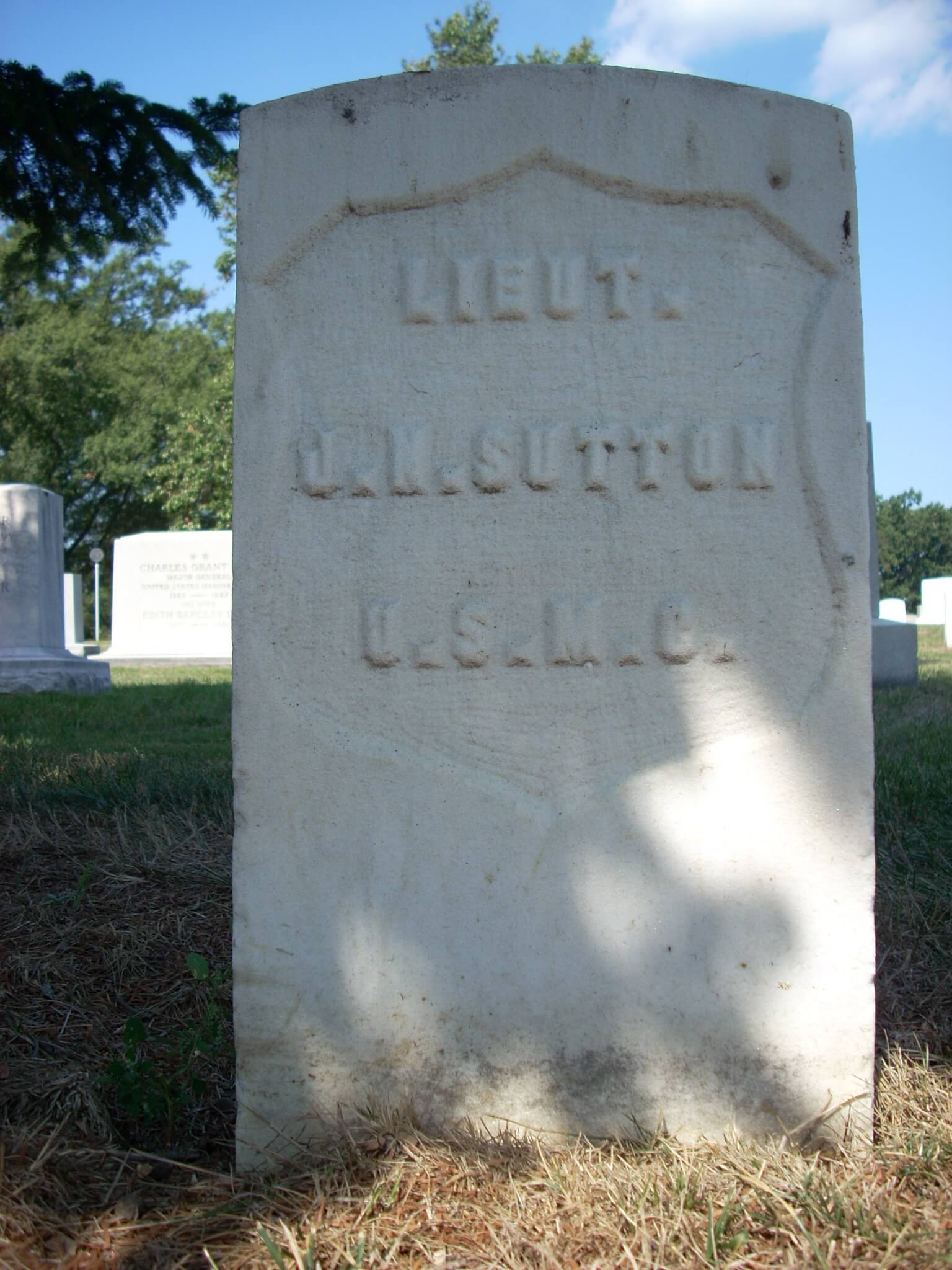

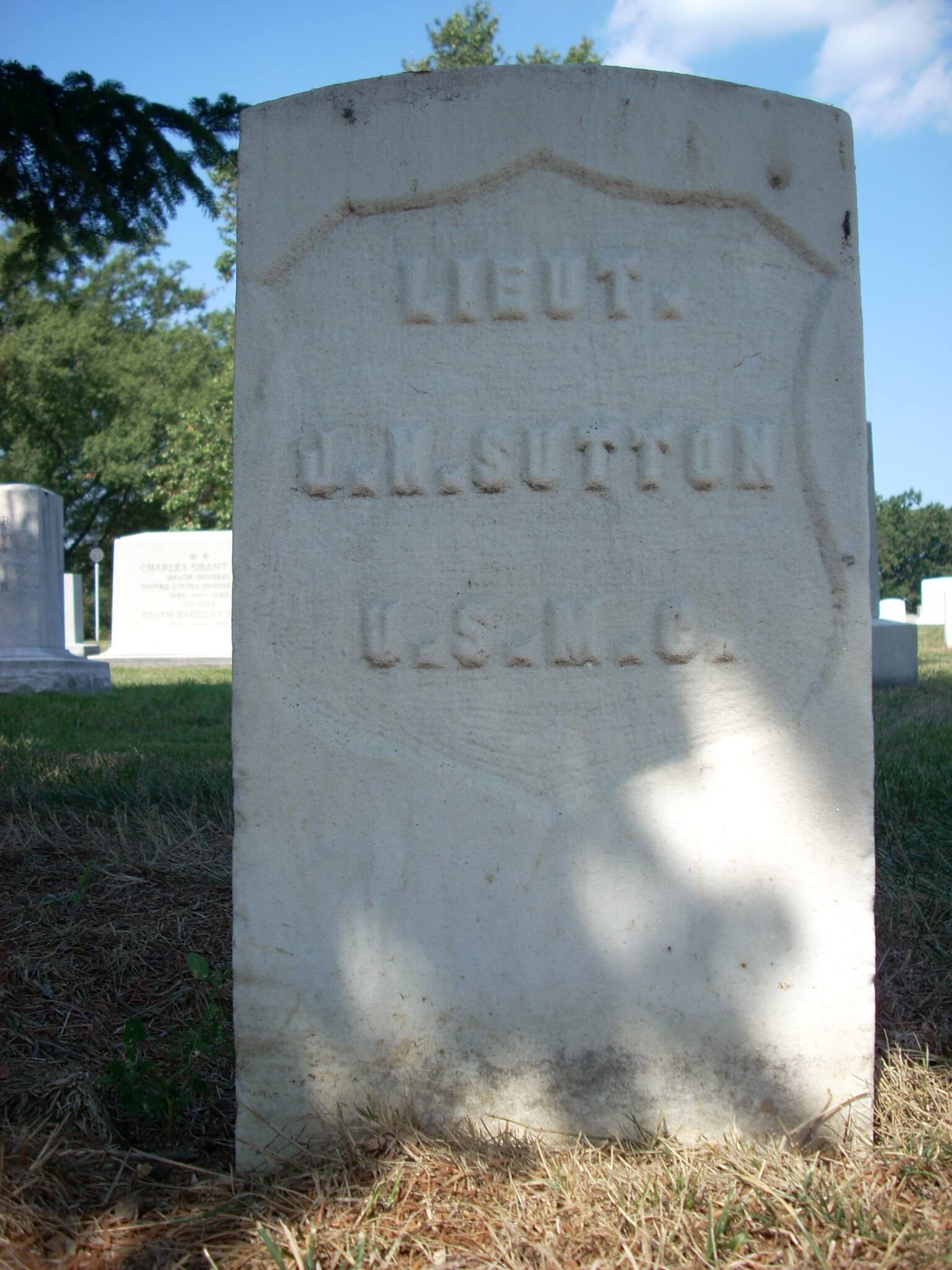

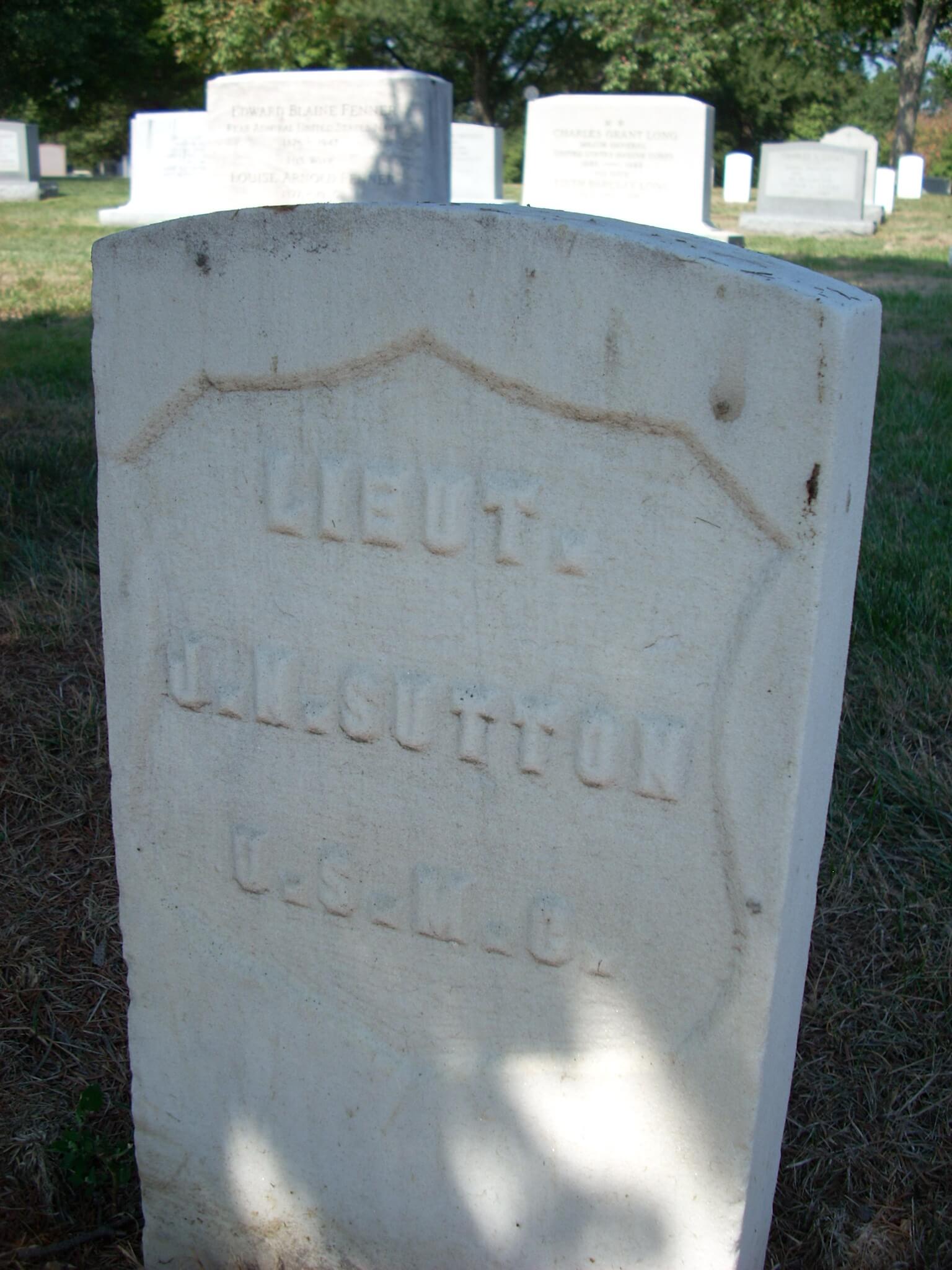

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – October 13, 1907 – Second Lieutenant James N. Sutton, Jr., United States Marine Corps, is dead at the Naval Academy Marine Barracks, his death resulting from a 32-caliber bullet fired into the right side of the head.

A board of inquiry detailed by Superintendent Badger, of the Naval Academy, has prepared a report which will be submitted to the Navy Department. From the best information obtained, Sutton, in company with Second Lieutenants R. E. Adams and E. P. Roelker, returned to the Marine Camp at 1:30 this morning, after having attended a dance at the Academy.

Shortly afterward Sutton is said to have been discovered on the road nearby with a revolver in his right hand and several officers attempted to disarm him. This they succeeded in doing, but not before the weapon was discharged in some manner and Lieutenants Adams and Roelker received slight wounds. Quick as a flash, it is said, Sutton took from his blouse another revolver and with this fired the fatal shot into his brain.

Lieutenant Sutton was 22 years old and the son of James N. Sutton of Portland, Oregon. He was formerly a Midshipman in the present senior class but resigned in his third class year.

SERGEANT TO TELL OF SUTTON’S DEATH

Sad Quarrel On Annapolis Parade Ground, Where The Lieutenant Died

Witness At First Hearing

But Was Not Asked About All The Circumstances – One Officer Gave Him A Revolver To Hide

WASHINGTON, July 10, 1909 – Sergeant James DeHart of the Marine Corps is looked to as the man who can solve the mystery that shrouds the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton, who was found dead on the parade grounds at the Naval Academy in Annapolis in October 1907, and who subsequently was adjudged a suicide by a board of inquiry.

Sergeant DeHart was present at the time of the fight in which Lieutenant Sutton died, whether by his own hand or at the hands of another. He was a witness before the Board of Officers that inquired into the affair, but he was not called upon to testify to all he knew.

DeHart, who is now stationed at the Marine Barracks here, was returning from a lark on the town with Lieutenant Roelker. The officer had made his way to his tent while DeHart was striving to get to his quarters without arousing the suspicion of the sentries. As he was slipping down a company street, his attention was attracted by the sounds of fighting and, his curiosity getting the better of him, he returned to see what was the trouble.

Four men were struggling in the darkness, which was only partly relieved by the light from the lamps of two automobiles. Subsequently, DeHart recognized the quartet as being Lieutenants Sutton, Utley, Adams and Ostermann. Just before he arrived on the scene, a shot was fired, and as he put it in an appearance one of the officers thrust a service revolver upon him with instructions to dispose of it. It was of .38-calibre and the regular Navy pattern.

DeHart, thoroughly frightened, flung the weapon from him. It must have fallen far out on the parade field, and immediately he wheeled and made his way quickly back toward his quarters. On his way there he met the Officer of the Day and told him of the fight and the disposition he had made of the revolver. He was instructed to seek out the weapon the first thing in the morning and to report with it at the officers’ tent. The next morning when DeHart went to seek it, the revolver had disappeared.

Although he had been a witness before the first board of inquiry, DeHart was not questioned as to which of the officers handed him the weapon or which one ordered him to dispose of it. The board contented itself with interrogating him as to his impressions of the affray and his connection with it. It went no further.

It is now believed that DeHart’s testimony at the coming hearing will throw a new light on the tragedy. The Marine will not divulge anything of his conversation on the parade ground when the officers were struggling and after the shot was fired, but his companions say he will talk freely on the witness stand when the Court is convened week after next.

Miss Margaret Stewart of Pittsburgh is present at Annapolis. She is generally reported at the young woman whose charms prompted the officers to engage in the fight that resulted in Lieutenant Sutton’s death. It is declared, however, that Miss Stewart was not along with Sutton on the night of the tragedy, but that she went to Carvel Hall in company with a Professor in the Naval Academy, and that Lieutenant Sutton was a casual caller.

This being the case, a new motive is being sought for the tragedy. It has been declared that the fight between the officers started over a young woman whose affections they all sought and who favored Sutton. The overthrow of this theory make the case all the more difficult, and the hearing before the court beginning July 19 promises to be exhaustive.

MERRY PARTY BEFORE SUTTON WAS KILLED

But He Drank Less Than Others, Says Clerk At Annapolis Hotel Where Officers Met

Chauffeur Heard Shot

Had Been Sent Away In Charge Of A Sentry Before It Was Fired, His Family Says – He’s To Be A Witness

From The New York Times Archives

ANNAPOLIS, July 11, 1909 – Two important stories were told today bearing on the mystery that shrouds the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton of the Marine Corps, who was found dead on he parade grounds of the Naval Academy in October 1907, and whose death, declared by a naval board of inquiry to have been by his own hand, is laid at the door of his brother officers by his family. These were that the young officer had not been drinking unduly on the night of the tragedy and that he was set upon in the automobile by four officers. These officers had been imbibing too freely, according to eye witnesses who saw the five leave Carvel Hall Hotel together.

These two stories will be brought out prominently at the hearing before the new board of inquiry, which convenes at the Academy one week from tomorrow. In the meantime, the opinion among the civilians of this quaint little Maryland city of that Lieutenant Sutton was murdered.

In naval circles, the utmost reticence is being observed and no opinions are expressed. The imminence of the meeting of the investigating board would have been enough to seal the lips of officers, but it was evident that the word had been passed that nothing shall be said that will tend to prejudice the court.

According to the clerk in the Carvel Hall Hotel, who was the last to see the five officers leave the place, Lieutenant Sutton was distinctly the most sober of them all. He did not have any opportunity to drink much that evening, for he spent it with Miss Margaret Stewart of Pittsburgh, who was stopping at the hotel, and was in the company of a Professor in the Academy. The little party remained in the lounging room on the main floor of the hotel, which is situated immediately behind the hotel office. The clerk noted them there from time to time during the evening.

“The effort to drag Miss Stewart’s name into the case is unwarrantable,” he said. “Lieutenant Sutton apparently had just been introduced to her, and, so far as I was able to discover, and I had plenty of opportunities, the other officers connected with the shooting had not met her. If the unfortunate officer was killed by one of his own fellows, it was not as a result of jealousy arising out of his intentions to Miss Stewart. Of that I am certain.”

The bar in the Carvel Hall closes at midnight, and shortly before that house, Lieutenant Sutton left Miss Stewart and the Professor, after bidding them good night. The hotel clerk witnessed the leave-taking, and saw Sutton hurry down stairs to the buffet, where Lieutenants Utley, Adams, Roelker and Ostermann had been for sometime. They had had numerous drinks and were in high spirits when Sutton appeared. Sutton, according to the bartender, drew his watch and noted the time.

“Hello,” he exclaimed. “It is five minutes to twelve. If you fellows want another drink you will have to hurry.”

Following his words, Lieutenant Sutton ordered a quart bottle of whiskey, together with a quantity of cracked ice, and several siphons of seltzer. The five then applied themselves to the liquor, and when they emerged to enter an automobile previously engaged by Sutton, the clark saw that they carried no bottle with them. Apparently they had finished it.

As they left the hotel the five seemed to be the best of friends. The hotel clerk would not admit that the four officers with Sutton were intoxicated, but he admitted that they appeared to be considerably exhilarated. They passed down the broad steps arm in arm and with a lot of laughter and apparently good natured chaff climbed into the waiting motorcar, which promptly shot off in the direction of the Marine Barracks.

William Owens was the chauffeur. What follows, the narrative of what he saw and heard is told by members of Owens’ family:

The car had but proceeded very far on its way before the four officers turned on Sutton, whose guest they were. Profane language was used, and when the machine reached a dark spot in the parade ground one of the officers ordered the chauffeur, Owens, to bring it to a stop. The four sprang out, dragging Sutton with them, cursing him as they did so.

Owens was alarmed at the situation, but he was quickly relieved of his anxiety when one of the officers called a sentry, “Get in there,” he commanded, “and take this man of off the grounds. Hurry up”

When Owens and the sentry were about a quarter of a mile away from the scene they heard a shot. Owens did not know what it meant. The next morning be learned of Sutton’s death.

The chauffeur slipped away into hiding today and could not be found. It was said that in the last two days no fewer than thirteen officers have called at his home to caution him against saying anything until the new board meets.

The old investigating board did not call upon him to appear, and his testimony was not sought. The fact that so much precaution is being taken now to prevent his being reached, either by newspaper men or friends of the officers under suspicion, leads to the belief that he knows much more than is generally supposed.

Owens has been in Washington three times within the last two weeks, and no secret was made at his home that he has been in consultation with Mrs. Sutton, mother of the dead officer.

These frequent consultations strengthen the opinion that Owens has knowledge that will lead to sensational developments. He undoubtedly knows the name of the officer who commanded him to stop at the lonely spot where Sutton lost his life, and likewise he must have identified the officer who disposed of the disquieting presence of the sentry under the pretense of sending him to take Owens and his machine to the gate. These two facts will be of the greatest importance, and especially so if the officers in both instances happen to be the same.

Very few officers remain at the academy who were there when the tragedy occurred. The few who are still on duty declined today to say anything about the case or to advance any opinions as to the real story of Sutton’s death. At the present time there are no officers of the Marine Corps at the academy, and those who belong to other branches of the naval service protest their complete ignorance of the matter because of their not being connected with the Marine Corps.

There are numerous stories afloat around this city as to Sutton’s peculiarities. None of them, however, can be substantiated, and they may have been set afloat by his enemies to discredit him. The dead Lieutenant, from all that can be learned, was not popular with his fellow officers.

One of these rumors is to the effect that Sutton was fond of posing as a “bad man” and of boasting of his prowness with a gun and his readiness to use one when provoked. It is said that on one occasion the young officer, while in uniform, cleaned out a resort. He did this at the point of a revolver, the report runs, and afterward boasted of it. Officers of the Marine Corps at the time resented this rumored action, as they believed it brought discredit on their organization.

Members of both the Marine Corps and the Regular Naval establishment are thoroughly incensed at the sensational stories being sent out from here. The dragging of the name of Miss Stewartt into the case is universally regretted, while the alleged confessions of the late Lieutenant’s bother officers that they hated him ardently are said to be made out of whole cloth. Such stories as that which declared Sutton’s rage to have been stirred to murderous heat by a blow that showed his nose to have been built up out of paraffin officers consider beneath notice.

Mrs. Sutton Parker, sister of Lieutenant Sutton, is expected here the latter part of this week. It is not known now just where she is, but it is generally understood that she is gathering further evidence to lay before the inquiry board. It was due to her activity in getting together additional evidence that Secretary Meyer ordered a rehearing of the case.

Dr. J. J. Muroht, head of the Emergency Hospital of Annapolis, who has served in the Regular Army in the Philippines, pointed out today that, although Sutton was called a suicide, he still was buried with military honors. “I have always understood,” said he, “that an Army man who ends his own life never had military honors at burial. In this case, however, the unfortunate man was buried with the honors of a Captain, when his rank was that of Lieutenant. When the body was removed from the Naval Academy grounds to the railroad station, a company of Marines accompanied it, and at the station a volley was fired from the rifles of these men.

This was done after the Naval Investigating Board had declared Lieutenant Sutton a suicide, and up to the present time I have not been able to understand or learn why this was done.

SUTTON INQUIRY PUBLIC

Secret Only If Evidence Points To Some One Man

From The New York Times Archives

WASHINGTON, July 14, 1909 – Secretary Meyer today decided to have the hearings of the board of inquiry which will investigate the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton public. No attempt will be made to take testimony in secret unless the testimony points to some individual as the murderer of Lieutenant Sutton. In that case the proceedings will be secret in order that the man under suspicion may have a chance to clear himself before he is openly accused.

Mrs. Sutton, mother of the Lieutenant, has declined to make any further comment ton the rehearing. She talked freely tonight, however, concerning the case of her other son, a cadet at West Point, who is in the hospital there as the result of what is said to have been hazing.

“I have dropped my investigation of the matter,” she said.”My son insists he received his injuries in a fall and although I am convinced he is taking this stand because of an exaggerated belief in the traditions of the academy, I cannot disprove his declaration. The academy authorities have endeavored to get at the bottom of the matter, but without success. As no proof can be had there is nothing on which we can work, and the matter, so far as I am concerned, has been dropped.”

Young Sutton’s injuries are of such a character, according to reports, that he could not have sustained them in a fall. He sticks to his story, however, and as he declined either to make charges or admit that he was the object of attack by upperclassmen, the authorities can take no action.

Mrs. Sutton was in conference today with her two attorneys. They went over the evidence carefully and framed the questions they were to put to the various witnesses that have been called. The drift of these questions was not made public. Neither Mrs.. Sutton nor her attorneys would talk. The former spent the evening in her apartments resting, she said, in anticipation of the hearing which begins on Monday.

Mrs. Sutton’s attention was called to the interview with Miss Elizabeth Stewart of Pittsburgh, printed in the New York Times this morning. In the interview, Miss Stewart denied that she had received the attentions of young Sutton, and that she was well acquainted with him. Mrs. Sutton accepted Miss. Stewart’s statement as being absolutely true. She acknowledged that, so far as she knew, there was no attachment between Miss Stewart and her son at the time of his sudden death. The elder woman regretted the connection of Miss Stewart’s name with the case.

Certain members of the court arrived in Washington today in preparation for reporting at Annapolis on Monday. They will confer tomorrow with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Winthrop to ascertain the procedures to be followed in the rehearing.

NO SUTTON “WHITEWASHING”

Navy Department To See That The Investigation Is Thorough

From The New York Times Archives

WASHINGTON, July 15, 1909 – Secretary of the Navy and the Judge Advocate of the Navy, it became known today, will maintain complete jurisdiction over the rehearing the case of Lieutenant James N. Sutton, the young Marine Corps officer who met a mysterious death on the night of October 13, 1907 at the Naval Academy.

While authority has been given to the members of a special board of inquiry to reopen the case, the Secretary will interfere if he sees the slightest inclination on the part of any one to strive to gloss the affair over. There is to be no “whitewashing.”

CHALLENGED SUTTON TO FIGHT A DUEL

Letter Found Among Dead Lieutenant’s Effects Said To Show Plan Was To Use Revolvers

Punishment For Officers

Members Of Sutton’s Party, If Cleared Of Murder Charge, Likely To Be court-martialed On General Conduct

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 15, 1909 – Evidence that Lieutenant James N. Sutton received a challenge to fight a duel has come to light. Two prominent men of Annapolis confirm the existence of documentary evidence showing almost conclusively that Sutton had been challenged to fight a fellow officer. The statement of Owens, the chauffeur, makes it probable that this is the explanation of the attack which the latter declares was made on Sutton when the party alighted from the automobile on the night of Sutton’s death.

One of the Annapolis men said tonight that a letter found in Lieutenant Sutton’s effects, and now in the possession of Mrs. Parker, his sister, showed that an arrangement for a fight or duel existed between Lieutenant Sutton and another officer, whose name was signed to the communication, but which he could not remember. The letter closed, he stated, with these words: “Lets call the gun-play off.” This is understood to indicate that there was an intention to have a duel with revolvers, but the foe of Sutton did not favor it.

Reports that young women of Annapolis, in society or out, have left town on the eve of the second investigation into the circumstances surrounding the death of Lieutenant Sutton do not seem to be borne out by he facts. Some of the young women here who knew Sutton, and these include practically all those who attended academy hops, are naturally on their vacations, but none has hurriedly left Annapolis since the reopening of the case.

Further it is stated authoritatively here tonight that with the possible exception of Mrs. Sutton, mother of the dead officer, and Mrs. Rose Sutton Parker, his sister, whose work has been largely instrumental in reopening the case, not a single woman has been seriously considered as a possible witness by the board which convenes on Monday.

Mrs. Sutton and Mrs. Parker will arrive in Annapolis tomorrow night and will stop at Carvel Hall, where Lieutenant Sutton and Miss Stewart spent the evening prior to the tragedy which closed the young officer’s career. The members of the court of inquiry, Captain Hood, senior member, and Lieutenant Jenson, the other naval representative on the board, are already in Annapolis, but have persistently refused to talk about the probable procedure of the court further than to say that they both favor an open court, so that the Navy and Marine Corps may clear themselves of any intimation that effort was made to hush up the matter or to hide any side of the question.

From reliable sources it was learned tonight that unless the family of the dead officer, through unimpeachable and clearly responsible witnesses, can show that he was murdered the young officers who were with him when he met his death will be cleared of any deliberate part in his death. From the same authority it was ascertained almost positively that Lieutenant Adams, and possibly, Ostermann, would in all probability be forced to face a general court-martial following the close of the second Sutton investigation.

That the young officers who were Sutton’s companions on the night he met his death were clearly guilty of serious breaches of naval discipline, and should have been promptly punished for their actions, aside from their connection with his killing, is the growing opinion in naval circles here. Officers will talk, but with the clear understanding that they are not to be quoted or their identification hinted at, and this is the consensus of their talk.

They say that had Adams and Sutton’s other companions been punished for their participation in that night’s doings the Navy Department would have then and there vindicated itself and the coming investigation been something that the department could have refused the family of the dead officer without laying itself open to any charges of hushing matters up.

Officers, particularly those of the Marine Corps, feel that their service is now on trial before the American people, and that in view of the fact that neither Adams, Utley nor Ostermann was punished or even summoned before a court now is the time to clear the service of hiding anything in the first investigation and to see that those who were in the mess are punished.

OWENS TELLS HIS STORY

Saw Adams Rush At Sutton And Heard The Latter Say He’d Fight

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 18, 1909 -With Major Henry Leonard of the Marine Corps, the Judge Advocate, the principal witnesses and an array of counsel here tonight, the Naval Board of Inquiry that will investigate the circumstances to determine whether Lieutenant James N. Sutton of the Marine Corps committed suicide, was murdered, or was the victim of an accidental shooting is ready to begin its sessions tomorrow morning.

Mrs. James N. Sutton and Mrs. Hugh A. Parker, mother and sister respectively, of the dead Lieutenant, with Henry E. Davis and Henry Van Dyke of their counsel, were among the first to reach the city here tonight. They are staying at Carvel Hall, as are all of the other persons who are connected with the inquiry, with the exception of Lieutenant Robert E. Adams, who is said to have taken a prominent part in the brawl that led to Sutton’s death, and Lieutenant Ostermann, who was also of the party of officers on the night of the tragedy.

Mrs. Sutton and her daughter reached the city shortly before 8 o’clock, and immediately went to the dining room with Mr. Van Dyke and took dinner. Dr. J. J. Murphy of Annapolis dined with them. Dr. Murphy attended Miss Mary E. Stewart, in whose company Sutton was a few hours preceding his death, when on the day following Sutton’s death she became ill.

A peculiar coincidence occurred upon the arrival of Mrs. Sutton and her party. William Owens, who was the chauffeur of the automobile that took Lieutenant Sutton and the other officers to the Marine Camp Grounds on t he night of the killing, and who is now a driver of an express company, had the job of taking their luggage to the hotel.

Owens told his story today in an interview.

“Sutton had hired me,” said Owens, “to take him out to the Camp in my automobile from Carvel Hall that night and when he came out of the hotel Lieutenant E. S. Adams and two other officers were with him. Sutton invited them to ride in his car. Adams got on the front seat with me, and the other three men sat in the rear seat.

“We went along King George Street ot he Oklahoma Gate of the Naval Academy grounds, where the sentry held us up. When told there were officers in the car he let us through, and we took the lower road across College Creek out toward the Marine Camp.

“Sutton and his companions in the rear seemed to be most friendly, chatting and laughing most of the time. When we got to within a short distance of the camp, I was told to stop.

“Adams jumped from the front seat and taking off his coat and hat, threw them on the ground. He made a rush for Sutton as he and the other officers got out of the car. The two officers grabbed Sutton by the arms, and I heard Sutton say: ‘Go away, Adams. I don’t want any trouble.’

“Then one of the officers told me to ‘beat it.’ As I turned the car around I saw Adams starting for Sutton again and heard Sutton say: ‘Well, if he wants to fight, I will fight him.’

“Then I went down across the bridge and met Griffith, another chauffeur, coming back with his automobile.”

Owens said that he did not hear any shots. In crossing the bridge on the return trip, he said he told the sentry stationed there of the trouble between the officers and that Sutton and Adams were two of the men.The sentry replied, according to Owens, that if they gave Sutton a fair fight, he would lick them all.

The Board of Inquiry will sift thoroughly every little detail in connection with Sutton’s death, according to Major Leonard, the Judge Advocate. He said that all together fifteen witnesses had been summoned to appear before the court. He said others would likely be summoned.

The court will open tomorrow morning at 10 o’clock, but Major Leonard said he wished to begin the sessions on the following days at 9 A.M. and to continue until 6 P.M. In this way, he said most of the work should be disposed of in three or four days.

There will be a hitch, however, in connection with the appearance of Lieutenant Utley, who Major Leonard is a material witness. Lieutenant Utley is assigned to the battleship North Carolina, which has just sailed from Naples for Providencetown, Massachusetts, and the cable message summoning him to appear at Annapolis did not reach the North Carolina before she sailed for the foreign port. Major Leonard said that it would probably be necessary for the court to take a recess for about two weeks, until histestimony could be obtained.

Lieutenants Adams and Ostermann have established their quarters in a boarding house directly across the street from Carvel Hall. Just after Mrs. Sutton and Mrs. Parker entered the hotel dining room the room was deserted, except for Adams and Ostermann. Mrs. Parker, who spent sometime at Annapolis at the former inquiry recognized Lieutenant Adams and spoke to him courteously. Mrs. Sutton was not informed of Adams’ presence in the dining room until after she had finished dinner. Then she expressed some surprise, but made no comments.

Lieutenants Adams and Ostermann were not in uniforms. Adams told a reporter that he had retained as counsel Arthur E. Birney, a former United States District Attorney of Washington. Neither Adams nor Ostermann would talk further than to deny absolutely all that has been credited to them in interviews. Lieutenant Ostermann said: “If Owens has any friends they had best warn him to be careful how he talks otherwise he may lay himself open to charges of perjury.”

Lieutenant E. S. Willing of the Marine Corps reached Annapolis today as a witness and is at Carvel Hall. During the course of a talk, Willing claimed that he was among those who reached the scene of the tragedy early after the shooting, and that he took a pistol, supposedly the one that killed Sutton, from the hand of the officer.

This was an entirely new development and created comment through the fact that Willing appears to have been a material witness in the first investigation but, not withstanding this fact, he was appointed recorder of that board and in a measure became a part of the inquest before he was a witness. Lieutenant Adams saw Willing’s name on the register and expressed pleasure that he was here. He and Ostermann made an effort to get in communication with him, but were unsuccessful. Later, however, Adams and Ostermann entered and automobile and went to the Marine Barracks to hunt up their former companion.

In an interview tonight attorney Van Dyke said that there had been no new material developments.

“I have come here, he said, “as one of counsel for Mrs. Sutton. We have laid no real plans, Our prime purpose is to clear the name of young Sutton from the stigma of suicide.”

Mrs. Sutton strongly reiterated her former statements that her son did not commit suicide, but was either shot by one of his fellow officers, or was accidentally killed.

Mrs. Sutton, Major Leonard says, may call any one she chooses at the inquiry.

SAW SUTTON SHOOT HIMSELF IN HEAD

Lieutenant Bevan Tells Court of Inquiry Story of Suicide, Upholding Lieutenant Adams

Threatened His Comrades

Tried To Get Guns To Protect Themselves – Once Shot Up The Camp, Officers Declare

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 20, 1909 – The proceedings at today’s session of the inquiry which is investigating the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton, U.S.M.C., of Portland, Oregon, took a sensational turn when First Lieutenant W. F. Bevan, U.S.M.C., now attached to the battleship New Jersey, took the witness stand near the adjournment of the court and reintered his part in the tragedy in the early morning of October 13, 1907, when young Sutton met his death. Lieutenant Bevan was Officer of the Guard in the Marine Camp on that night and was one of the first men to reach the scene of Sutton’s death.

Like Lieutenant Adams, he testified that Sutton deliberately shot himself, but beyond that cardinal fact his description of Sutton’s alleged suicide varied in important details from the story told by Adams, the man who said he had participated in a life and death struggle with the young Lieutenant just prior to his act of self-destruction.

The most glaring disagreement with Adams’s story came when Bevan testified that two officers were on top of Sutton trying to hold him down, to prevent his using his revolvers, when Sutton freed and arm from under him and fired a bullet into his own brain after some one remarked that Sutton had killed Lieutenant Roelker. Adams testified that he had risen from Lieutenant Sutton’s body and that Sutton lay exhausted and along on the ground when he raised his right hand and fired the shot that ended his life.

Bevan’s testimony also revealed that a situation bordering on a Wild West rampage had existed in the Marine Camp just prior to the shooting, when Sutton had been trying to make Lieutenant Roelker dance by leveling two revolvers at his feet and afterward rushed from the camp, disregarding his arrest, by the officer of the guard, and shouting that he would quit the Marines for good and all.

In addition to Lieutenant Bevan, Lieutenant Adams and Lieutenant Ostermann were on the stand today. Lawyer Davis, Mrs. Sutton’s counsel, completed his cross-examination of Adams in quick order after court opened and then Lieutenant Ostermann took the stand and his direct and cross-examination took up most of the day. Ostermann was a member of Sutton’s automobile party on the night of October 12 and corroborated Lieutenant Adams’s story except to add that he believed that Sutton was badly intoxicated that night.

Commander John Hood, senior member of the board of inquiry, was called upon to make rulings today on objections raised to the questions by both Major Leonard and Mr. Davis. As the proceedings advance more caution is being exercised by the Judge Advocate as well as the other interested attorneys, to sub the latitude hither to allowed the witnesses in testifying. Major Leonard said at the adjournment of court today that he did not expect the inquiry to be completed this week.

Lawyer Davis began to question Adams today about an interview he had with Sutton’s sister, Mrs. Hugh A. Parker, shortly after young Sutton’s death. Mrs. Parker, who is attending the hearings with her mother, had wanted to question all the young officers who were supposed to know something about her brother’s death. She has asked Adams to grant her a talk along, and tell the truth about the matter, according to the testimony.

“I want you to state again if you saw Lieutenant Sutton kill himself,” Mr. Davis asked.

“As I have said, I saw Sutton draw a revolver from under him in his right hand, like this (illustrating the motion), turn his head, like this (illustrating the motion), saw the flash jump about six inches,” Lieutenant Adams replied.

Mr. Davis pressed the question as to whether Sutton fired the fatal shot with the large service revolver or the small one.

“It wasn’t very light around there,” said Lieutenant Adams, “but it was my idea that he shot himself with the small revolver.”

Mr. Davis called the witness’s attention to his testimony of yesterday, in which he said quite positively that it was the small weapon.

“I have told you half a dozen times already this morning that I did not positively identify the gun,” said the witness. “It didn’t seem as if it was as large as the service gun.”

Mr. Davis referred to a reported interview with Adams in a New York paper of July 7, in which Adams was quoted as saying the Suttons were trying to “trump up a murder charge against two who were innocent,” and asked the witness if he had said anything like that.

“Major Leonard, the Judge Advocate, objected to this line of questioning.

“This witness knows what he is charged with,” said Major Leonard. “He knows there are no charges against him as far as the Department is concerned.”

Mr. Davis argues that, if besides obtaining counsel Adams had made a statement that he considered himself accused of murder, it had a direct bearing upon his credibility as a witness to show whether he was testifying under a veiled sense of guilt or as any ordinary witness might do to enlighten the court truthfully upon all the facts.

Commander Hood, presiding, ruled that Adams did not have to answer the question.

Mr. Davis questioned the witness in regard to his interview with Mrs. Parker, Sutton’s sister, soon after Sutton’s death.

“Did Mrs. Parker ask you at that time to make a statement of the truth of this whole affair?” asked Mr. Davis.

The witness said he believed she did.

“Did you make such a statement?”

“No sir,” replied Adams.

“Assuming that you di make a statement, did not Mrs. Parker afterward tell you that it was not the truth?” asked Mr. Davis.

Adams said he did not remember making such a statement. “I have told you before that I told Mrs. Parker to look up the records for the testimony of the first hearing if she wanted to find out anything, and furthermore, Mrs. Parker was willing to talk with the other officers in two and threes or bunches, but she wanted to see me alone.”

Mr. Davis read from the assumed interview with Mrs. Parker, and asked the witness if he remembered making the statement. Adams said he could not remember making any such statement to Mrs. Parker.

The statements Mr. Davis credit the witness with having made to Mrs. Parker gave a somewhat different version of the tragedy to what which Adams has given on the witness stand.

Mr. Davis thereupon announced he was through cross-examining Adams for the present.

Major Leonard asked the witness a number of questions in regard to the interview with Mrs. Parker. Lieutenant Adams caused a burst of merriment on the part of Mrs. Parker, her mother and counsel when he declared that Colonel Doyen, senior officer, had told him that Mrs. Parker was “a very shrewd looking woman.”

Lieutenant Edward A. Ostermann was called as the next witness.

“Where were you and what were you doing from 8 P.M. to 2 A.M. on October 12 and 13, 1907” was the first question Major Leonard asked the witness.

Starting with the hop at the Academy and meeting with Sutton later, about midnight, at Carvel Hall Hotel, the witness told substantially the same story as told by Lieutenant Adams.

“We were in a room at Carvel Hall about 12 o’clock,” he said, “when Lieutenant Sutton appeared at the door with a bottle of whiskey in this hand and asked us to have a drink. We told him we were not drinking whiskey and he went away. About twenty minutes later he came back and said he had an automobile outside, and asked if we did not want to ride to camp. I don’t think any one made an answer, but we all went out and Lieutenants Adams, Utley and Sutton and myself got into an automobile and started for the camp.”

From that point on Lieutenant Ostermann told of the fist fights with Sutton by Adams and himself near the Marine Camp, and later running down to where the shots were fired he found Lieutenants Adams and Bevan standing near where Lieutenant Sutton and Lieutenant Roelker lay on the ground.

“Someone said Sutton has killed Roelker and then killed himself,” the witness said.

In answer to further questions my Major Leonard, Ostermann said the reason he and his friends refused to take a drink with Sutton at Carvel Hall was because Sutton was not wanted in the party.

“He was unpopular with his classmates,” the witness said. “Then, too we had been drinking beer all day and didn’t want to drink whiskey.”

Ostermann told of an incident about a month prior to Sutton’s death, when Sutton “shot up the camp.”

“I was awakened by the bullets whizzing through our tent,” said the witness, “and stepping our on the camp street, saw Sutton standing in the door of his tent firing his revolver. Major Fuller came along and asked Sutton to give him his revolvers and he finally handed them to Major Fuller.”

“How long did it take you to get from where you heard the shots to the point where the altercation occurred?” inquired Major Leonard.

“About a minute.”

“Who did you see there?”

“Lieutenants Adams, Bevan, Utley, Roelker and Sutton.”

“What did Adams do so say?”

“He showed me his finger and said Sutton had shot him. It was bleeding profusely.”

The witness said Roelker was lying in the road and just picking himself up as he got there. “It was pretty dark where the shooting occurred,” the witness proceeded, “but you might be able to see a revolver fifteen yards away.”

On cross-examination by lawyer Davis, Lieutenant Ostermann was asked about Miss Stewart of Pittsburgh, the young woman with whom Sutton is said to have spent the evening prior to the shooting. Ostermann admitted seeing Sutton and a young lady at Carvel Hall, but could not remember having been at their table.

“Something was said by Adams and Utley about going into a private room to have some beer,” said Ostermann, and in answer to further questions he admitted that the party had been cautioned twice to be quiet.

Ostermann insisted that no argument took place in the automobile on the way to camp until Lieutenant Utley suggested that if Sutton were to do any beating he had better do it now.

Ostermann said he knocked Sutton down at least three times in the fight that they had on the way to the camp and the last time Sutton got up he started up the road and disappeared. Ostermann, Adams and Utley remained there for a few minutes discussing the possibility of Sutton carrying out his threat to shoot them all, and then went to the guardhouse to get some guns. They did not find anyone at the guardhouse and all three started for the barracks to report to the Officer of the Day, when Utley ordered Adams to go down to the scene of the fight and see if he could find any clothes. Soon after Adams started down the road. Ostermann and Utley heard the shots and ran to the scene of the shooting.

First Lieutenant William F. Bevan, U.S.M.C., now attached to the battleship U.S.S. New Jersey, was the next witness. The witness was Officer of the Guard on the night Sutton was shot. Major Leonard asked him to relate the incidents of the night of October 12-13 from midnight on. In response Lieutenant Bevan said:

“Some one reported to me about 1 o’clock that a fight was going on in the Marine Camp. I went up there and found Lieutenant Sutton in his tent door, with a revolver in each hand, pointing them at Lieutenant Roelker’s feet, who was remonstrating with Sutton and trying to get him to put up his guns. I placed Sutton under arrest and ordered both men to their tents.

“Sutton made some remark about disregarding arrest and ran down the walk, exclaiming he was going to leave the camp for good. Shortly afterward I heard several shots fired and Lieutenant Utley and I ran down toward the parade grounds where we saw several figures. There we found Lieutenant Ostermann and Sergeant De Hart sitting on Lieutenant Sutton’s body. Lieutenant Adams was standing nearby and trying to get at Sutton to hit him. Some one had pulled him away from Sutton and was holding him.

“I stooped down and took hold of Sutton by each shoulder, intending to hold him down on the ground so that he could not use the two revolvers he had when I last saw him. Some one said ‘My God! He has killed Roelker.’ and then I felt a movement under me and saw Sutton extend his arm from under him to the right side of his head and shoot. Then his body relaxed.”

“Lieutenant Willing reached down and took the revolvers.”

SUTTON SHOT IN TOP OF HEAD, SAYS DOCTOR

Could Have Killed Himself, But Witness Shows It Would Have Been Difficult

Disputed By Colonel Doyen

Declares The Wound was Lower –

Willing Threatened With Arrest For Being Late At Trial

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 22, 1909 – The remarkable variance in the testimony of some of the several officers who are witnesses before the court of inquiry which is investigating the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton at the Naval Academy two years ago, was emphasized at today’s hearing by contradictory evidence as to the location of bullet wound which caused Sutton’s death.

The question of the location of the wound has assumed importance. It would appear that it would have been a much more difficult matter for Sutton to have shot himself, lying prone on the ground with three men on top of him if the bullet entered the top of his skull, as Surgeon George Pickrell, in charge of the Marine Hospital at that tine, who examined Sutton’s body, testified it did.

Colonel Charles A. Doyen, Commandant of Marines at that time, and holds the same post now, testified that he examined Sutton’s body immediately after the shooting, felt the wound in his head, and that it was located on the right side of his head a little behind and on a line with the top of the ear. Dr. Pickrell thought Sutton might have inflicted the wound upon himself, but he made an unconvincing and awkward demonstration in court with the revolver, although he had a free right arm.

Considerable progress was made today and three more witnesses were disposed of. Despite Surgeon Pickrell’s and Colonel Doyen’s testimony, Mr. Davis, counsel for Sutton’s mother and sister, finished the cross-examination of Lieutenant Willing, who was on the stand a part of yesterday.

Willing made an unsatisfactory witness under cross-examination. The few discrepancies which Mr. Davis showed by reading the record of his description of the scene of the shooting at the former inquiry were readily conceded by Lieutenant Willing, with the remark that he testified from the best of his recollection on both occasions.

Mr. Davis tried to find out from all the witnesses today what became of Sutton’s two revolvers after the shooting.

Colonel Doyen testified that he saw them and ordered Lieutenant Willing to take charge of them, but he did not know what became of them until they finally got into his hands at the inquest. It was apparent that no one of the officers wanted to assume the responsibility of having the weapons about him immediately after the shooting. Sergeant James De Hart of the Marine Corps, the last witness at today’s session, testified that some officer at the scene of the shooting handed him a revolver with the curt command to “take this.” It was dark and he could not see who the officer was. De Hart soon afterward threw the revolver into the bushes on his way to the barracks, and on going out to look for it next morning could not find it.

An incident of the forenoon was a rebuke administered by Commander Hood to Lieutenant Willing for being late for the second time, and he was expected to take the witness chair. He could offer no excuse, and the commander threatened him with arrest for contempt of court if there was a repetition of the offense.

A large number of women attended the hearing today. The young girls in their light gowns, accompanied by white uniformed officers, gave the courtroom a Summer background.

Lieutenant Edward S. Willing resumed the stand at the opening of the court. Mr. Davis, counsel for Sutton’s mother, continued his cross-examination of the witness. Willing, according to his testimony reached the scene of the tragedy in time to see Lieutenants Adams and Sutton in a fisticuffs prior to the shooting. Mr. Davis took the witness over and over the scene of the fight between Adams and Sutton but could not materially shake the officer’s story.

Mr. Davis read from the records of the former inquiry, bringing out some discrepancies in Lieutenant Willing’s testimony. The witness said in his present testimony was correct.

“The former testimony was given on the same day of the shooting, and some of it was reckless,” was the Lieutenants explanation.

Once he answered: “I can’t remember what everybody said and did on that night. No one could.”

Mr. Davis handed a rusty 38-calibre revolver to the witness and asked him if he could identify it as the one he picked up on the edge of the parade ground the night that Sutton was shot. Willing broke the revolver, looked it over carefully, and said it might be the same one, as its caliber and appearance were the same. The members of the board also examined the revolver. Mr. Birney, Lieutenant Adams’s counsel, questioned Lieutenant Willing at the conclusion of Mr. Davis’s cross-examination.

Commander Hood showed the witness the rules in the Navy Blue Book, pertaining to Willing’s duty as Officer of the Day at the time of the shooting, and asked him if he did not know he should have arrested anyone who was unruly. Lieutenant Willing said he did not recall whether or not he knew the rule at that time.

“Did you tell one of officers to let Adams go ahead and knock Sutton’s head off?” asked Mr. Davis.

“Yes, I think that I made such a remark,” Lieutenant Willing answered.

Lieutenant Willing was excused and Surgeon George Pickrell, who was in charge of the Naval Academy Hospital on the night of the shooting testified. Dr. Pickrell heard the shots while he was standing in a window of the hospital, which was but a short distance away, and hurried to the scene. He examined Sutton’s injuries and made a careful examination of the bullet wound in his head after his death.

The bullet entered Sutton’s head on top, near the back of the head and a little to the right, the witness said. This has been a much disputed point as other physicians have testified that the wound was just back of the right ear. Dr. Pickrell stated that the shot was fired within two feet of Sutton’s head and in his opinion could have been self-inflicted. He said that Sutton’s body showed no other injuries which might have caused his death.

Surgeon Pickrell said that he treated Lieutenants Adams, Ostermann, Roelker and Potts at the hospital shortly after the shooting. They had insignificant injuries. They were all very much excited and talked about the shooting. Lieutenants Adams and Ostermann, as he recalled it, told him about the fight and said Sutton had shot himself while he was lying on the ground.

The witness identified a belt and holster he said was strapped on Sutton’s leg the night of the shooting.

In answer to Mr. Davis’s questions on cross-examination the surgeon said he had made a thorough examination of Sutton’s wound, although he had been careful not to disturb anything which should have been there for the inquest.

At Mr. Davis’s request the witness demonstrated with the revolver in the manner in which he believed Sutton might have shot himself. Dr. Pickrell was first careful to see that the revolver was not loaded. He took the revolver in his right hand, extended his arm above his head, with his elbow bent at an awkward angle, and pointed the muzzle directly at the top of his head toward the middle and rear of the skull.

The women spectators in the courtroom seemed to enjoy the exhibition. There was an audible giggling among them. Mrs. Sutton and her daughter among them. Mrs. Sutton and her daughter smiled as Dr. Pickrell broke the revolver to see if it was not loaded.

Colonel Charles A. Doyen, senior officer of the Marine Corps at Annapolis at the time of the Sutton affair and now, was the next witness. Colonel Doyen said Lieutenant Utley approached him that night and told him that Sutton had killed Roelker and then shot himself.

Mr. Davis objected to the testimony as hearsay.

“I want to save time,” said he.

“We have all the time we want,” retorted Major Leonard.

“Of course,” said Mr. Davis. “The United States Marine Corps is eternal; I am mortal.”

When Colonel Doyen reached the scene, he said, he picked up Sutton’s right hand, which was extended directly in front of his body, and felt for his pulse. He found he had a pulse, and ordered one of the officers nearby to hurry and get the Naval Academy Physician, Dr. McCormick. Sutton was dead before they could get him to the hospital.

Colonel Doyen described the incidents of the shooting as they had been reported to him by the young officers concerned in the fights. He said the officers had special leave on that night because of the hop, but were due in the camp at 1 o’clock.

Major Leonard questioned Colonel Doyen on redirect examination. The witness said that subsequent to the time Lieutenant Willing brought the two revolvers to him after the shooting he did not know who had them until they were returned to him at the inquest. He had told Lieutenant Willing to take charge of them.

Colonel Doyen told of a report made to him in May 1907 that Lieutenant Sutton had been placed under suspension for ten days for being under the influence of liquor and creating a disturbance in the camp. He said he knew Sutton spent much of his time alone. This attracted his attention and he made inquiries and was told that Sutton did not seen to be popular.

“I was told he was overbearing and assumed a manner of superiority toward his brother officers,” Colonel Doyen said.

Colonel Doyen said the bullet wound in Sutton’s head was on the right side one inch back of the right ear on a line with the top of the ear. He said he felt of Sutton’s head as he lay on the ground. Dr. Pickrell’s location of the wound earlier in the day had placed it on top of the ear near the rear.

Sergeant James De Hart was the last witness of the day.

De Hart created considerable amusement in court by frankly admitting he had been out with friends and was “slightly under the influence of liquor” On the night in question. He said, however, he knew what was going on around him. When Mr. Davis presses the questions about his mental condition that night, Major Leonard asked that judicial notice be taken of the fact that De Hart was intoxicated. The young Sergeant’s mind was quite hazy in regard to anything that was said or done that night but he was positive that he was not one of the men sitting on Lieutenant Sutton. Lieutenant Bevan previously testified that he was.

He was making his way to camp by “a back entrance” when he met Sutton prior to the shooting. De Hart said that Sutton carried two revolvers and that he, De Hart, did not stop to talk with him long. The witness did not know about the trouble Sutton had in camp, but thought something was up when he saw the two revolvers. Soon afterward De Hart heard the shots and ran back to the scene of the shooting. He could not remember recognizing any officers then except Lieutenant Utley, who ordered him to the barracks.

“I did not go then,” he said, “but stayed in the grass near by out of curiosity.”

Mr. Davis had not finished his cross-examination of De Hart when at 4 o’clock court adjourned for the day. Commander Hood, senior member of the board of inquiry, announced this afternoon that court would adjourn tomorrow afternoon until Monday morning.

In answer to the request of the Judge Advocate before adjournment, Mr. Davis announced that his clients had one witness outside of those already subpoenaed by the Government, whom they would like to call. He is Charles Kennedy, a Private in the Marine Corps at Norfolk, Virginia.

NAVY RESTS ITS CASE IN SUTTON INQUIRY

Coming Witnesses For Some Days Regarded As Those For The Suttons

De Hart’s Memory Fails

Can’t Remember Who Were About Sutton – Expect New Light

On Shooting From A Witness

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 23, 1909 – The Navy practically rested its case today in the investigation of the circumstances surrounding the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton. After a short session today, Commander John Hood, U.S.N., President of the Court of Inquiry, adjourned the hearing until Monday. With the exception of Lieutenant Harold H. Utley and Surgeon F. F. Cook, recently attached to the battleship North Carolina, and now on the way to this country from Europe, nearly all the remaining witnesses are considered to be witnesses for the interested parties outside of the service. As Utley and Cook are not expected here before August 1, the inquiry next week will take the color of “the other side.”

It was said today that the Suttons would call an eye-witness to the shooting who would throw an entirely different version on the affair. Counsel would not disclose the name of this witness, but it was thought that it would be Private Charles Kennedy of the Marine Corps, now stationed at Norfolk, Virginia. Kennedy has been subpoenaed at the request of the Suttons.

Mrs. Rose Sutton Parker, the sister, is not expected to testify before next week. She will probably tell in detail the interview that she had with Lieutenant Adams shortly after her bother’s death, which Adams practically denied in his testimony. Mrs. Sutton will also take the stand.

Henry E. Davis of Washington, counsel for Sutton’s mother, expressed himself as satisfied with the developments in the case this week.

“Nothing has developed to change our judgment and theory of the case,” he said.

Most of today’s session was occupied with the testimony of the two chauffeurs, William L. Owen sand Edward Griffith. Owens testified that he drove Sutton and a party of young officers from Carvel Hall Hotel to the Marine Camp on the night of the shooting and witnessed an altercation and interrupted fist fight between Sutton and Lieutenant Adams as he left his passengers near the parade grounds, adjacent to the camp. He was told to “beat it,” he said, came back to town and did not learn of the shooting until the next morning. Griffith, who had driven Lieutenant Potts and another officer to the camp just ahead of Owens, testified that he met the Sutton party on his way back. He did not see any fight or hear any loud words, he said. His testimony in other details corroborated that of Owens.

Lieutenant Roelker, who is supposed to have been hit with a bullet from Sutton’s revolver during the quarrel, has not yet been located, although his testimony is considered most important. The list of witnesses remaining to be examined consists of Lieutenants Utley, Surgeon Cook, Lieutenant Templin M. Potts, Jr., Professor Gilbert P. Coleman of the Naval Academy, Frank Fogg of Washington, Mrs. Sutton and her daughter, Mrs. Parker.

Owens testified that in the automobile from Carvel Hall toward the camp, Lieutenant Adams sat on the seat with him and Sutton and the other two officers, whose names he did not know, on the rear seat. This was about 1 o’clock. Sutton and his two companions talked and seemed to be friendly only the way out. Adams did not have anything to say. They went through the Naval Academy grounds and nothing happened until they got across the cemetery bridge on the” dump” when some one told him to stop.

Lieutenant Adams jumped from his seat and threw off his collar and coat and made a rush at Lieutenant Sutton as the latter got out of the car, Owens said. The witness heard no argument which might suggest trouble before that. The other two officers grabbed Sutton, and the witness heard Sutton say, “Go away, Adams, I don’t want any trouble.” Then someone told him to “beat it.” He turned his car around and lingered.

“Why didn’t you go then?” asked Major Leonard.

“I wanted to stay and see the fight if there was to be one,” said the witness.

Owens said he saw Adams make another rush at Sutton, and heard Sutton say, “If he wants to fight, I will fight him.”

The one of the officers called “Orderly.” Owens was sure that they did not say “Sentry” or “Patrol,” and he started back with his car. He told the sentry on the bridge about the trouble and sentry said, “If they give Sutton a fair fight, he will whip them all.”

He did no hear of the shooting until the next morning, the witness said. He did not think any of the officers had been drinking or that his car made enough noise to drown the lowest voice.

Questioned by Mr. Birney, Lieutenant Adams’s counsel, Owens said he did not think the two officers were holding Sutton to restrain him from attacking Adams but it was his impression that they were trying to make it easier for Adams.

On cross-examination Owens told of taking Lieutenant Sutton, another young man and a young woman (Miss Stewart) from Carvel Hall to the Maryland Hotel at 7:30 that evening. The young man got out and Lieutenant Sutton and the young woman returned to Carvel Hall in his car.

Adams was excused until Monday. Lieutenant Adams took the witness stand at the opening of the afternoon session to make some corrections in his testimony in the records. They were principally of a typographical nature.

Edward Grittith, the chauffeur who took Lieutenant Potts and another officer to the Marine Camp just ahead of Sutton’s party, testified. He partly corroborated Owens’ story. Griffith was with Owens at Carvel Hall and saw Sutton there before the automobile started for the camp, he said. Later, on his way back, he met Owens and his party, who had stopped on the dump, and he recognized Sutton, Adams and Utley. He did not see or hear any fight.

Griffith was excused and an adjournment was taken until Monday morning.

SUTTON’S SKULL FOUND FRACTURED?

Said In Annapolis That Doctor Who Made Autopsy Will Testify That It Was

Other Injuries Reported

Mrs. Sutton Goes To Washington On Report That Her Trunk Had Been Robbed –

Finds It Safe

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 24, 1909 – In support of the theory of Mrs. Sutton and her daughter that Lieutenant Sutton was practically beaten to death, it is said today that the report of the physician who performed an autopsy upon the body of Lieutenant Sutton will show that Sutton’s skull was fractured, that there was a large lump under the cheek, and that his forehead bore evidences of a terrific blow. A gash, evidentially inflicted with the butt of a revolver, will, it is said, be proved to have been found on the top of Sutton’s head. Dr. McCormick, who performed this autopsy, is to be one of the most important witnesses of the coming week.

Pending the resumption of the investigation into the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton of the Marine Corps before the Naval Board of Inquiry here Monday, counsel for Sutton’s mother and sister are occupied today in examining the voluminous records of the testimony taken already, with a view to a more rigid cross-examination of the remaining Naval witnesses.

The testimony of chauffeur Owens yesterday, which indicated that young Sutton had tried to avoid a fight with Lieutenant Adams and the other officers who were taken to the camp in Owens’s car on the night of the shooting, has thrown the first light on the affair from a witness outside of the service.

Sutton’s mother and sister, Mrs. Rose Sutton Parker, were very emphatic in their declarations today that the facts would yet be brought to light to show that Lieutenant Sutton was beaten to death on the night of October 12, 1907.

Charles Kennedy, the Private in the Marine Corps at Norfolk, Virginia, who is said to be an important witness of the Suttons, arrived here today. The nature of his testimony has not been disclosed, but it is thought he was an eyewitness of the shooting, and that he will give a different version of the affair from that of the witnesses who have thus far testified that Sutton committed suicide.

SUTTON INQUIRY ON TODAY

Witnesses Will Be Called To Disprove Suicide Theory

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland –July 25, 1909 – “I am not vindictive; all I desire is to clear my brother’s name from the disgrace of suicide,” said Mrs. Rose Sutton Parker, sister of Lieutenant James N. Sutton, tonight.

With the opening of the second week of the investigation into Sutton’s death tomorrow witnesses will be called on “the other side” to refute the theory of suicide.

Mrs. Parker will perhaps be the principal witness in that respect. Her testimony is expected to disclose several important points in refutation of the suicide theory, based on the facts obtained by her and her mother in their work in the past two years, which resulted in the reopening of the case. She will probably not testify until the remaining two or three Navy witnesses on hand are disposed of.

Professor Gilbert P. Coleman of the Naval Academy and Lieutenant Templin M. Potts, Jr. of the Marine Corps, will probably be witnesses tomorrow. The inquiry is likely then to occupy two or three days now and then adjourn until August 1, when Surgeon F. C. Cook, U.S.N., and Lieutenant Harold H. Utley of the Marine Corps, who have been subpoenaed as witnessed, are expected to arrive from abroad.

SENTRY SAW SUTTON AND ADAMS FIGHTING

Sutton Called Him To Hold Cap And Blouse, Witness Tells Inquiry Court

Says Utley Found Pistol

Willing And Ostermann Deny They Handed Revolver To De Hart

Mrs. Sutton May Testify

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland –July 26, 1909 – Testimony that Lieutenant James N. Sutton and Lieutenant Adams were in a hot fist fight on the night of Sutton’s death, and that this fight once interrupted, was resumed, was presented unexpectedly at today’s session of the naval inquiry into Sutton’s death. These happenings were described by Charles W. Kennedy, a Private in the Marine Corps, now stationed at Norfolk, Virginia, but a sentry on post at the Marine Camp on the night of Sutton’s death.

Kennedy dropped into the situation like a bolt from a clear sky, and told a frank, straightforward story of some of the incidents prior to the shooting which has not been mentioned by any of the officers who have already testified. Thought he was a witness to the encounter between Sutton and Adams on the night the former was shot, Kennedy’s name has not been mentioned by the witnesses concerned in the affair.

His testimony supported the contention of Sutton’s mother and sister that Sutton did not seek the fights with Adams and the other officers. In attacking his credibility, Major Leonard, the Judge Advocate, , went into the Private’s record, and showed that he had been disciplined on several occasions in the service.

Kennedy said that he had been reluctant to mention his parting the affair because Lieutenants Utley and Adams, his superiors, had both admonished him on the morning of the shooting to “keep quiet.”

On his way to relieve a sentry at o’clock on the morning of the shooting he had come upon Sutton, Adams, Ostermann and Utley in an angry argument, the witness said. Adams was in his shirt sleeves read for a fight and Sutton accosted Kennedy and asked him to hold his blouse, cape and cap.

“All right, Adams, if you want to fight I’ll fight you,” he heard Sutton say.

They fought hard for a few minutes and Sutton’s face was bloody, when Lieutenant Utley intervened and stopped the fight, saying the guard would be out if they did not stop.

A second time he saw Adams and Sutton come together, as he was returning to his post. Half an hour later Kennedy heard the shots from his post at the Naval Hospital, and soon after Adams appeared at the hospital and volunteered the information to Kennedy that Sutton had shot himself, and that Adams had had his finger shot off.

Utley also told him at the time that Sutton had killed himself, the witness said. Next morning both officers cautioned him not to say anything about the affair. At early drill the following morning the witness said he saw Utley go up to the edge of the parade grounds and pick up a .38 caliber Colt service revolver, which Utley carried into the barracks with him. The incident had been observed by other Privates in the company the witness said.

Kennedy’s testimony was shaken neither by the cross-examination of Adams’ counsel, Mr. Birney, nor by that of Major Leonard.

Dr. McCormick, who as present at the autopsy held on Sutton’s body and examined the bullet wound back of and slightly above the right ear. Dr. Pickerel has testified that it was the top of the head.

To test Kennedy’s testimony, lawyers Davis and Van Dyke, Mrs. Sutton and Mrs. Parker, and several newspaper men went to the parade grounds after and adjournment of court and took the various positions from which the witness said he saw and heard the fights. Lawyer Davis said afterward that their case would rest principally on the testimony of Kennedy and Mrs. Parker.

Mrs. Sutton, mother of the dead officer, will probably be called as a witness. It is understood that she will be able to identify a written challenge and a subsequent apology from one of Sutton’s brother officers in the Marine Corps written but a short time before Sutton’s death. The young officer who challenged Sutton to a duel has not yet been subpoenaed as a witness, but it is expected he will be summoned as a result of Mrs. Sutton’s testimony. This, it is said, would tend to show that young Sutton was not of quarrelsome mind and after receiving a challenge he persuaded the sender to exchange mutual apologies instead of having any open trouble.

Several former witnesses were recalled at the morning session and questioned by Mr. Davis as to whether any of them had handed a revolver to Sergeant De Hart on the night of the shooting, as De Hart had testified. They all denied it.

The first of those witnesses as Lieutenant Edward A. Ostermann. Ostermann said he did not see a revolver given to De Hart and did not know who gave it to the Sergeant.

“But I have a recollection that some one did hand him one of the revolvers,” added the witness.

Lieutenant Edward S. Willing was recalled and denied having handed the weapon to De Hart. He said that he heard afterward that somebody had given De Hart a revolver, but he never heard who the officer was.

William L. Owens, the chauffeur who drove the officers to the camp on the night of the tragedy, was then recalled. He corrected his testimony. He desired to say that he had heard one of the officers call for the sentry instead of orderly after Sutton and his companions got out of his car.

Owens said he thought that “orderly” and “sentry” meant the same thing when he testified previously. Owens said that has had not been told since he testified that they were different ranks.

Major Leonard closely questioned Owens on this point when the chauffeur testified last week. At that time Owens insisted that the call was for an “orderly.”

Edward Griffith’s, the other chauffeur, was recalled and testified that he heard the cry of “sentry.” Owens’ and Griffith’s testimony did not agree as to the relative locations of their cars on the night in question.

Mr. Davis, Mrs. Sutton’s counsel, suggested to Commander Hood that as the witnesses on hand would not carry the proceedings beyond tomorrow, an adjournment might be taken until next week when Surgeon F. C. Cook and Lieutenant Harold H. Utley of the Marine Corps, the two witnesses now abroad, are expected to arrive.

The court, however, decided to continue the sessions from day to day until all the witnesses who might appear were examined.

There are no other naval witnesses at hand now, and it is thought that Mrs. Sutton and Mrs. Parker will testify tomorrow.

MRS. SUTTON NOW CHARGES OFFICERS

Government Forces Her To Accuse Lieutenants And Sergeant De Hart Of Her Son’s Death

Case Adjourned For Week

Lieutenant Utley Will Return Before Hearings Are Resumed

Mrs. Sutton’s Letter to Secretary of the Navy

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland – July 27, 1909 – When Mrs. Sutton was called as a witness by the Judge Advocate, her own counsel being undesired of putting her on the stand at this time, she was asked to identify a letter which she wrote to the Secretary of Navy last February, urging a reopening of the inquiry into her son’s death. In it she expressed the belief that new evidence could be adduced to show that Lieutenant Sutton was killed by one of his brother officers.

As soon as this letter was introduced in evidence, Major Leonard requested the court to place Mrs. Sutton on the stand as complainant against Lieutenants Adams, Bevan, Willing, Ostermann and Sergeant De Hart of the Marine Corps, all of whom were at the scene of the tragedy on the night young Sutton was shot.

Mrs. Davis insisted that Mrs. Sutton’s sole objective was to clear her son’s name of the stigma of suicide and not to direct the finger of suspicion against any particular person or persons. The court sustained the Judge Advocate’s position. All the officers named were called into court and notified that they had been made parties defendant to the inquiry and henceforth had the right to be present and cross-examine witnesses.

They all took seats at the long inquiry table where Lieutenant Adams and his counsel have sat throughout the proceedings. Because Lieutenant Utley was also a witness to the shooting and had the right to be present as a defendant, the court was adjourned by Commander Hood until he should return.

Mr. Davis said afterward the only thing which had prevented a Federal Grand Jury inquiry in the first instance was Mrs. Sutton’s desire to have the record of the former brand of inquiry changed.

Mrs. Sutton’s letter which formed the basis of the Government’s new attitude was written on February 8, 1909, and referred to the petition for a new investigation made by Senator Jonathan Bourne of Oregon. The letter thus spoke of her petition:

“That is it should be found that one of the other participants in the affray, in which my son lost his life, was criminally responsible for his death or probably so responsible, such further action as may be deemed appropriate may be taken for the purpose of bringing the person so thought to be responsible to trial and punishment if convicted.”

Mrs. Sutton added that he own investigation convinced here that her son was killed by one of Sutton’s brother officers.

NAVY WON’T CHANGE SUTTON RULING

Usual To Make Person Placed On Defensive A Defendant

Withrop Tells Davis

Board Not A Trial Court

Mrs. Sutton’s Lawyer Wrote To Navy Department That

The Situation “Smacks Of The Scandalous”

WASHINGTON, July 30 – The ruling of the court of inquiry investigating the death of Lieutenant James N. Sutton at Annapolis, Maryland, will not be interceded with by the Navy Department. In a letter addressed today to Henry E. Davis, counsel for Mrs. Sutton, mother of the dead officer, Beekman Winthrop, Assistant Secretary of the Navy, stated that the department, in view of the facts, declined to accede to his request to vacate the ruling of the court by which Mrs. Sutton was declared to be regarded as a “complainant of accuser” while all persons present at the time of the death of Lieutenant Sutton were regarded a “defendants.”

In his letter, Winthrop said that the ruling did not change the nature of the court.

“It is the invariable practice of courts of inquiry that if during an investigation any person is placed on the defensive by the evidence adduced, or by any of the circumstances of the case, to notify each person of the fact that to explain to him his rights in the premises.

“In considering this action it should not be lost sight of that if the court finds that Lieutenant Sutton’s death was not the result of his own act, but was caused by another person or persons, such other person or persons, so accused, will undoubtedly be brought to trial for the offense.

“This is no way shifts the burden of proof, as you apparently assume, as the court is in no respect a trial court, nor does it place upon Mrs. Sutton or her counsel the burden of determining who was responsible for Lieutenant Sutton’s death.”

Mr. Davis, in his letter to Secretary Meyer, protesting against the ruling of the court, said:

“By its action the court has undertaken to relieve Lieutenant Utley from his obligation to refrain from conference with the witnesses who have preceded him and has put it in his power either to stand mute or else have the benefit of full and free conference with the witnesses who have presided him and of access to the testimony before the Board of Inquest, a situation which I am constrained to say so strongly smacks of scandalous as of itself to call for your intervention.”

MISS NEEDED RECORD IN THE SUTTON CASE

Page That Would Show If Kennedy Was Sentry Is Stolen, Say Officials

Harriman Aiding Suttons?

Lieutenant Sutton’s Father Is A Division Superintendent

On A Harriman Railroad In The West

ANNAPOLIS, Maryland –August 2, 1909 – Unless corroborative evidence other than of a documentary nature can be found the question of whether Private Kennedy of the Marine Corps was or was not on duty as the cemetery patrol the night that Lieutenant James N. Sutton was killed will never be answered. A Government record which would settle the question is missing.

When he was grilling the man on the witness stand, Judge Advocate Leonard attacked Kennedy’s record and said that he would prove that the Private of Marines was thoroughly unreliable. Mrs. Sutton and Mrs. Parker at once said that the authorities here would attempt to show that Kennedy was not on duty as a sentry as he had testified and therefore did not pass by the scene of the fight or see the firing from the high hill overlooking the ground where Sutton died.

“But they will never be able to prove this,” they said.

Their prediction has come true – probably not as they intended. One page of the record of men on sentry duty at any given hour for years past is missing. It is the page which covers the twenty-four hours in which Lieutenant Sutton’s death occurred.

The Marine Corps and the Naval authorities here say boldly that the record was stolen. The fact that Kennedy’s story that he was on duty that night is absolutely uncorroborated will be brought our when the investigation reopens on Thursday, and this will be made a part of the official report of the board.

The Suttons appeal to the Taft administration for a reopening of the case was granted quickly, while a fight of over a year, when Roosevelt was in the White House, was unavailing. It was said that E. H. Harriman is backing their fight not only morally but financially. Mr. Sutton, father of the dead officer, is the division superintendent of one of Mr. Harriman’s Western Roads and the two are close personal friends as well as business friends.

After an absence from Annapolis since the adjournment of court last week, Lieutenants Adams and Ostermann, defendants in the case, returned to Annapolis today. Since the adjournment Captain Hood and the other members of the court have visited the locality of the tragedy and have gone over the ground carefully, with particular reference to the testimony of Private Kennedy. The trip was made late at night, that the circumstances surrounding the inspection might resemble as nearly as possible those of the night of the shooting.

SUTTON INQUIRY TODAY

Lieutenant Utley, Now A Defendant, May Refuse To Answer All Questions