From a press report: 30 December 2002

The coming assault on Baghdad already has its first hero: Colonel John Boyd, a foul-mouthed, insubordinate fighter pilot who has been in his grave at Arlington National Cemetery for almost five years.

When Iraq’s tyrant is brought down, that inevitable victory will be Boyd’s doing. You won’t hear Boyd’s name being cited in Rose Garden speeches, however. Nor will the Pentagon be authorising any posthumous decorations for the man who, through 30 years of bureaucratic guerilla warfare, transformed America’s military.

Even though he gave them many of the tools that made Operation Desert Storm such a sweeping success in 1991, the brass continued to hate Boyd with such a passion that, as a final sign of contempt, they sent only a single general as their official representative at his funeral.

But without his influence, the US would almost certainly be preparing to enter Iraq much as it fled Saigon: a vast, muscle-bound killing machine based on the assumption that big budgets and expensive weapons assured victory.

That approach didn’t work in Vietnam, nor even in tiny Grenada, where a US expedition force required two days in 1983 to subdue a squad of 200 Cuban construction workers.

“Thank God they have dumb sons of bitches in the Kremlin, too,” Boyd fumed not long after. “If they weren’t thick as ****, Grenada would prove how weak we really are.”

Boyd’s disgust was palpable. Army units on the island couldn’t call in artillery support from Navy ships because their radios worked on different frequencies. Nor could soldiers on the ground stop air strikes hitting the wrong targets. Almost 30 Americans were killed in the conflict, most the victims of friendly fire.

“Grenada was confusion cubed,” Boyd told me in 1985, after the Pentagon released a report whitewashing the invasion’s flaws and follies. “Our top guys know the first rule of warfare: always protect your rear.”

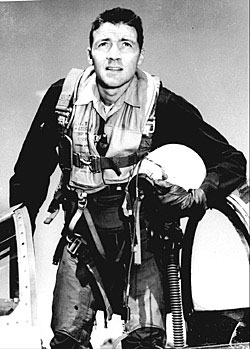

Boyd devoted the latter half of his career to catching those generals with their pants down. The first half had been spent in the cockpit, first over Korea and later as an instructor at the US Air Force “Top Gun” flight schools.

Had he been just another joystick virtuoso, Boyd would have had a traditional career: step by step up the ladder until retirement, when he could have been expected to join one of the weapons companies, pitching former colleagues on the latest, gold-plated guns, planes and tanks.

That’s how the procurement game had always been played at the Pentagon, where a weapon’s usefulness was of secondary importance to its cost. Big budgets still mean bigger staffs for the Pentagon’s project-development officers – and bigger salaries, too, when they leave to work for General Dynamics, Grumman, or Boeing. To Boyd, the system produced “gold-plated **** shovels” that “hurt us more than the enemy”.

So, after rewriting the air combat rulebook he began looking at the broader flaws in US military theory. They were, he concluded, the same ones that had led to disaster in Vietnam, the ultimate symbol of which he saw as the F-111.

“The only good thing about the F-111,” he said, “is that the dumbass Soviets believed our propaganda and built their very own piece of useless ****, the Backfire bomber.”

His idea of the perfect fighter plane was the F-16. Small, cheap and simple, it used only enough technology to make it a more efficient killing machine – fly-by-wire control systems to save the weight of hydraulics, one engine to keep it small, cut costs and make it hard to target.

When superiors tried to silence his criticisms by pushing him into a dead-end office job, Boyd developed the concept on the sly by “stealing” a million dollars worth of computer time, giving his brainchild a variety of misleading names and slipping the evolving concept past bureaucratic enemies before they realised what they had just authorised. It earned him a wealth of grief.

There will be plenty of F-16s over Iraq pretty soon, but that won’t be Boyd’s greatest contribution. Of much greater impact will be the culmination of his life’s work, a treatise on military tactics that he penned after retiring to Florida and seeing the F-16 accepted, against all odds, as a frontline mainstay.

“He called it Observe-Orient-Decide-Act – commonly known as the OODA loop,” says Boyd’s biographer Robert Coram. “Simply rendered, the OODA loop is a blueprint for the manoeuvre tactics that allow one to attack the mind of an opponent, to unravel its commander even before a battle begins.”

To Coram and others, including Defence Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, Boyd is “the most influential military thinker since Sun Tzu wrote The Art of War 2400 years ago”.

So why should pacifists cheer the memory of a man whose life was devoted to perfecting the use of martial force? Because, if the Iraq invasion goes even remotely according to plan, Saddam’s downfall will be short and relatively bloodless. Isolated, unable to trust his generals and with his every move tracked by the cheap, plentiful, all-seeing Predator drones that Boyd also helped to develop, Saddam will have two options: surrender or perish.

The Baghdad campaign will reflect Boyd’s greatest insight, the one he borrowed from Sun Tzu. The sweetest victory, said the Chinese sage, is the one that does not demand a battle. Even if you have the weaponry to win it at a canter.

From a News Report December 9, 2002

The leader was “Genghis John,” his troops “the Fighter Mafia,” and their project “the Lord’s work.”

In a few cramped Pentagon offices, a volatile but brilliant Air Force Colonel secretly led a handful of other pilots and engineers in the development of a revolutionary aircraft design.

They pored over drawings of wings and fuselages, prodding and occasionally bullying contractors. They studied variables for thrust, lift and drag, then shipped their calculations to a co-conspirator in Florida who had access to computers that could analyze and spot flaws in the data.

As the Air Force brass touted the new F-15 Eagle and the Navy worked on the F-14 Tomcat, Colonel John R. Boyd and his henchmen dreamed and schemed of a lighter, more nimble plane that would out-perform both and cost less.

“It was one of the most audacious plots ever hatched against a military service and it was done under the noses of men who, if they had the slightest idea of what it was about, not only would have stopped it instantly, but would have cut orders reassigning Boyd to the other side of the globe,” author Robert Coram writes in a new book about Boyd, who died of cancer in 1997.

Helped along by a handful of senior officers and congressmen dubious about official claims for the Eagle and the Tomcat, Boyd and his gang provided the intellectual energy for what would become the F-16, a warplane now flown by 22 nations and hailed as the most successful fighter aircraft in history.

Thirty years later, as Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld pushes the development of weapons systems that promise to transform today’s military, Boyd’s story may serve as both inspiration and warning.

The saga demonstrates that radical change is possible, even in the world’s most notoriously hidebound institution, but suggests it must bubble up from deep within the ranks.

“Rumsfeld is trying . . . to impose change from the top down,” complained Franklin “Chuck” Spinney, one of the few members of the Fighter Mafia still working in the Pentagon. “And what that means is that they have to have an answer they’re trying to impose. . . . The problem is, they haven’t done the research to see if that answer is actually workable.”

In contrast, Boyd, the Mafia’s godfather and the central figure in the broader military reform movement it spawned, was a cigar-chomping, free-cursing dynamo, notorious for challenging convention and questioning authority at every level. He was endlessly revising projects he’d spent years developing.

Some of Boyd’s Mafia also worry that Rumsfeld’s vision of transformation relies too heavily on gadgets and not enough on human intellect.

Boyd “would be appalled” that Osama bin Laden remains beyond the reach of the U.S. military 15 months after the September 11 attacks, said one Boyd contemporary who, because of his continuing association with the military, asked to remain anonymous. The al-Qaida leader, said Boyd’s contemporary, is demonstrating how an ability to stay ahead of the opposition in thought and movement can frustrate the most advanced technologies.

Though he hit his stride as a flier a half-century ago, Boyd remains a legend among fighter pilots. Training young aviators in Nevada during the 1950s, he became known as “40-second Boyd” because of his offer to pay $20 to any opponent who could evade him for more than 40 seconds in air-to-air maneuvers; none ever did.

In the 1960s, when contemporaries called him the “`Mad Major,” Boyd developed the “`Energy-Maneuverability Theory,” a revolutionary way to measure the performance of different aircraft. It demonstrated the superiority of the Soviet MiGs then in use in Vietnam, spurring development of the F-15.

And in the ’70s, convinced that the Air Force had overloaded the Eagle, Boyd not only led the Fighter Mafia, he fathered a way of thinking about warfare that continues to influence the U.S. military and foreign forces.

Embraced most enthusiastically by the Marine Corps, Boyd’s theories were critical to development of strategies that helped the United States win the Persian Gulf War of 1991; carried into the private sector, they’ve been adopted and adapted by businesses such as Toyota, General Electric and Wal-Mart.

Coram, whose book “Boyd” was three years in the making and reached bookstores last month, is a veteran reporter and pilot. He argues that Boyd may have been the most important student of warfare since Sun Tzu, the Chinese scholar whose 2,400-year-old essay, “The Art of War,” is still a touchstone for military officers.

“Sun Tzu gave you a rulebook,” said Mike Wyly, a retired Marine colonel who helped spread Boyd’s ideas through the Corps. “What Boyd said is way more applicable in actual thinking about tactics and strategy.”

Boyd built on Sun Tzu’s teaching that the surest way to victory is to so confuse the enemy that he is rendered unable to fight. He read voraciously, simultaneously studying human behavior and the history of warfare, in particular battles in which outnumbered or ill-equipped forces defeated enemies who seemed clearly superior.

He concluded that successful commanders managed to think and act ahead of their foes. In a briefing titled “Patterns of Conflict” and delivered over the years to hundreds of military and civilian officials, he broke decision-making into a continuous four-step cycle — observe, orient, decide, act — and demonstrated how the successful commander wins by “getting inside the loop” to disrupt and ultimately paralyze his opponent.

Boyd took six hours to deliver the briefing. He never reduced it to writing because he never considered it finished, Coram writes.

One policymaker who heard Boyd’s brief in the 1980s was a Wyoming congressman with a strong interest in defense. His name was Richard B. Cheney. As Secretary of Defense a few years later, he brought Boyd back into the Pentagon for private sessions on plans for war in Iraq. Cheney, now vice president, told Coram last year that Boyd “clearly was a factor in my thinking” as those plans evolved.

“We could use him again now,” Cheney added. “I wish he was around. . . . I’d love to turn him loose on our current defense establishment and see what he could come up with.”

Coram recounts how Mafia-member Spinney, watching the 1991 war unfold on television at his home in Alexandria, leaped from his chair as a U.S. military spokesman described how thousands of Iraqis were surrendering to Americans who’d gone around their strongholds to hit targets and sow confusion behind the lines.

“We kind of got inside his decision cycle,” the spokesman told reporters.

Spinney blurted an epithet, grabbed the phone, and called Boyd. “John, they’re using your words to describe how we won the war!” he said. “Everything about the war was yours. It’s all right out of `Patterns.’ ”

Coram calls Boyd “the most important unknown man of his time.” He also was among the most difficult.

Secretaries regularly were reduced to tears by his profanity, and superior officers often noted his unkempt appearance; he neglected his family, living with his wife and five kids in a series of tiny apartments well below their means. Two of the children have struggled for most of their lives with depression, and the family worried that a third might boycott Boyd’s funeral.

The inattention to his children mirrored Boyd’s own upbringing. His father, a salesman in Erie, Pennsylvania, died a few days before John’s third birthday; his younger sister had polio as a child, and after their father’s death their mother “had to spread herself thin among all of us children,” Boyd once told an Air Force historian.

Boyd “was the most intense man I’ve ever met or known,” said Jim Burton, a retired Air Force Colonel. Burton, along with Spinney and a few other Boyd associates, came to be known as his “acolytes.” The group grew accustomed during the 1970s to 3 a.m. phone calls from Boyd, who would talk for hours on some point of aircraft design or military strategy.

Boyd was so focused, “you could not communicate with him unless his mind was willing to allow that,” Burton said. The acolytes trained themselves to recognize when “the window was open,” he said.

At one time or another, most of the acolytes got what they call the “fork-in-the-road speech.” It was a jarring perspective on life in the Pentagon.

As Coram recounts it, Boyd would tell them that a day would come when “you’re going to have to make a decision about which direction you want to go.” Then he would point his hand to the left or right.

“If you go that way, you can be somebody. You will have to make compromises and you will have to turn your back on your friends. But you will be a member of the club and you will get promoted and you will get good assignments.

“Or”, he said, pointing in the other direction, “you can go that way and you can do something — something for your country and for your Air Force and for yourself. If you decide you want to do something, you may not get promoted and you may not get good assignments, and you certainly will not be a favorite of your superiors. But you won’t have to compromise yourself.”

Ray Leopold, now a vice president of Motorola, was not quite 28 when he heard the speech. He had come to Boyd’s Pentagon office with a reputation as one of the brightest young officers in the Air Force; he left having sacrificed his career by helping Boyd document a coverup of the spiraling costs of the B-1 bomber.

“It was the most fun I ever had in the military,” Leopold says today.

As the speech suggests, Boyd was incorruptible and contemptuous of those — in uniform or out — he saw as attempting to push inferior ideas or sell inferior products to the military.

As a major he was nearly court-martialed for cursing out a Colonel and calling him and a roomful of other officers liars. He rescued his career by convincing a General he was right.

Coram describes how a defense contractor once sent its top aircraft designer to meet with Boyd during early planning for what would become the F-16. The man brought aerodynamic estimates for a plane that Boyd quickly recognized as bogus.

Boyd studied the figures, leaned over the charts and said, “I can extrapolate this thing back to where the wing has zero lift. Wow. This airplane is so good that not only does it have zero lift, it has negative drag. . . . If this thing has negative drag, that means it has thrust without turning on the engines. That means when it is on the ramp with all that thrust, even with the engine turned off, you got to tie the . . . thing down or it will take off by itself.”

Boyd ended the conversation: The “airplane is made out of balonium.”

His former associates argue that Boyd would render a similar verdict on Rumsfeld’s attempts to transform today’s military, though the secretary’s demands for a more agile force would seem in line with Boyd’s thinking.

Boyd “was a technologist at heart,” said Chet Richards, who runs a Web site, belisarius.com, dedicated to carrying Boyd’s ideas about strategy into the business world. But Boyd’s focus, he said, was always on people and their thought processes.

The current Pentagon leadership, in contrast, seems convinced that technology itself is the key to victory, Richards argued. He said Boyd would view as nonsense today’s talk of “network-centric warfare,” and its claim that netted sensors can give commanders a perfect picture of the battlefield.

Others among Boyd’s acolytes worry that not only is Rumsfeld’s transformation headed in the wrong direction, but the military’s culture has become so careerist that it is now impossible for insurgents like Boyd to bring different ideas to the fore.

Today’s young Pentagon officers see that the path to advancement is the successful procurement of new weapons, said Pierre Sprey, the acolyte probably closest to Boyd. The establishment “is vastly more corrupt and openly so,” he asserted. That “causes you to retain fewer and fewer real warriors.”

“We need a mechanism of rewarding and listening to leaders who think differently,” said Tom Christie, who computer-checked the Mafia’s math for the F-16.

Now the Defense Department’s director of operational testing, Christie heads a small staff that regularly deflates contractors’ claims about new systems. The young officers who rotate through his office are dedicated, he said, but it’s hard for them to keep faith when systems of questionable merit continue to be funded.

A handful of Boyd associates, including some of the acolytes, have met each Wednesday night for more than 20 years around a quiet bar in the basement of the Officers Club at Fort Myer, less than a mile from Arlington National Cemetery where their mentor is buried.

The usual talk is of Spinney’s continuing battles with the Pentagon bureaucracy — he was a key player a few years ago in bringing concerns about “wing drop” in the F/A-18 Super Hornet to public attention — or gossip about the latest test results or cost overruns on planes such as the F/A-22 Raptor or MV-22 Osprey.

For last week’s gathering, several dozen of Boyd’s friends and admirers turned out to meet and toast Coram, reminisce about old battles, and recall those middle-of-the-night phone calls from Genghis John.

The evening was a reminder of how important Boyd had been in his life — in all their lives — Christie said, and at times he could feel himself tearing up.

“John’s spirit is here with all of us. We had some great times, and I sure miss him.”

Sunday, March 16, 2003

The wild blue yonder was truly his workshop

By Andrew Hamlin

Courtesy of The Seattle Times

The mortal remains of Air Force Colonel John Richard Boyd went into the ground at Arlington National Cemetery on a rainy day in late March 1997. Only two of his fellow Air Force officers attended, one a three-star general representing the chief of staff. The general “sat alone in the front row and was plainly uncomfortable.” A flight of F-15s looked in vain for an opening in the clouds — due to inclement weather, his service would not end with the customary flyover.

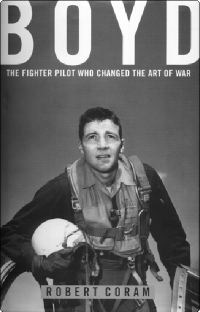

It was a fitting coda to the improbable career of Boyd. In “Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War,” Robert Coram recounts the life of a brilliant warrior and iconoclastic military thinker who spent his life and his formidable intellect battling the military’s bureaucracy in the service of his revolutionary ideas.

For the Air Force, Boyd wrote his “Aerial Attack Study,” the first codification of fighter-pilot combat tactics. He topped that with E-M (Energy-Maneuverability) Theory, showing with one fairly simple equation how an aircraft performed by optimizing both pilot performance and aircraft design. He pushed this integral datum through the Pentagon, creating the F-15 and the lightweight F-16 fighters, still USAF mainstays.

“Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War”

by Robert Coram

Little, Brown, $27.95

At Boyd’s funeral, a sizable contingent of Marines dwarfed the Air Force representation. At graveside, a senior Marine Colonel placed the globe-and-anchor insignia beside the urn of ashes; it is the highest posthumous honor the Corps can bestow. In retirement, Boyd developed a fighting system that transformed the Marines. He did so through endless reading — 323 books plus — and ultramarathon telephone calls to the few he trusted, his Pentagon protégés known as the “Acolytes.”

He’d analyzed ground warfare throughout history and emerged with optimized combat applications for any given situation. The Pentagon didn’t like to use Boyd’s name — he’d cursed and humiliated them enough — but his system found fruitful application everywhere from Grenada to the Gulf War to the business world.

At the same time, Boyd percolated “Destruction and Creation,” included as an appendix in Coram’s book. He wanted “only” to explain the nature of creativity. To take it apart and put it back together again like a machine gun, while achieving a synthesis of Godel’s Proof, Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle and the second law of thermodynamics.

In “Boyd,” the Acolytes and others share stories of the man’s insatiable intelligence, and the many reasons he never made general, including proud loud-mouthed intolerance for any perceived inferior, rank be damned. They tell of the courts-martial and investigations he faced and the superior officers he chewed out, finger jutting at their chests and cigar ash spilling down the uniforms of men holding his future in their hands. At least twice while exceptionally enraged, Boyd simply set neckties on fire with the glowing butt of his omnipresent Dutch Master.

On the home front, the Colonel housed his wife and five children in a tiny apartment in a shady neighborhood. His oldest son, crippled by polio, helped neighbors by fixing a great many televisions and stereos which had mysteriously fallen off trucks.

Boyd once siphoned off an estimated $1 million worth of computer time from Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to use in perfecting his Energy-Maneuverability Theory. The investigating officer told him, finally, that no charges would be filed. Given that, would Boyd be so good as to explain how he performed his trick?

Boyd’s preface to that answer could serve as his epitaph. “My goal was not personal. My work was for the best interest of the country. I tried to do it the Air Force Way and was refused at every turn.

“Then I did it my way.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard