Courtesy of the United States Army and Dr. Steven E. Anders

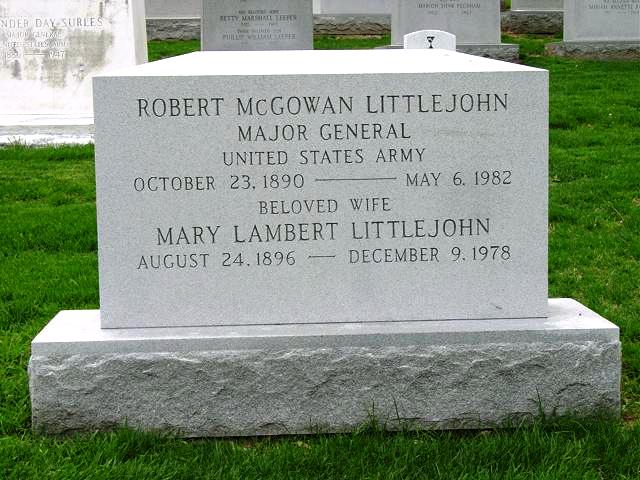

Major General Robert M. Littlejohn–Chief Quartermaster in the ETO

Dr. Steven E. Anders

Quartermaster Professional Bulletin – Autumn 1993

US Army Photo

Logistics-once defined simply as “gitten stuff” –entails what many perceive as the unglamorous side of war. Its successes are often taken for granted, while even the slightest failure is deemed unpardonable. General Brehon B. Somervell, head of the Army Service Forces in World War II, had it about right when he said:

“Good logistics alone can’t win a war. Bad logistics alone can lose.”

For more than two centuries the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps has sustained the Army with vital supplies and field services, without which victory in our many past conflicts would not have been possible. Rommel’s oft-quoted remark that “the battle is fought and decided by the quartermasters before the shooting begins,” is a shrewd bit of advice applicable even today.

Few Quartermasters, though, can ever hope to achieve the kind of instant notoriety or long-term recognition accorded their combat arms brethren. The brilliant Revolutionary War strategist Nathanael Greene knew all too well what he was being asked to sacrifice, when, as a favor to General George Washington, he agreed to become Quartermaster General of the Continental Army in the wake of Valley Forge. His lament at the time-“No body ever heard of a Quarter Master in History”-still resonates. There have been exceptions, of course, but they are few and far between.

In the case of World War II commanders, vast stores of collected records, published memoirs, and weighty biographies have long since ensured the places in history of Eisenhower, Marshall, MacArthur, Bradley, Patton, and others. Even corps and division commanders, if not always house-hold names, are at least well known to students of military history. The same hardly holds true for key logisticians of World War II, whose names are anything but familiar, despite their many successes and quite sizable contribution.

If I were to compile a list of outstanding logisticians for World War II, at or very near the top of that list would be the Chief Quartermaster for the European Theater of Operations, Major General Robert M. Littlejohn.

Littlejohn was handed an enormous task by the Supreme Allied Commander. He faced an endless array of logistical problems, any combination of which might have undone a man of lesser stamina and ability. Yet he managed to turn in a winning performance.

Why? In my view he was the right man for the job, uniquely qualified through decades of training and experience to hold the senior most Quartermaster position in the European Theater. While others may disagree, I also think he had, on balance, the necessary temperament as well.

Born in 1890, in Jonesville, SC, Littlejohn attended Clemson Agricultural College for a year before entering the United States Military Academy in 1908. His student days at “the Point” left an indelible stamp, and he made close ties and associations that were to last a lifetime. As a student, Littlejohn was best known for his athletic prowess. Strong, barrel-chested and determined. he quickly made his reputation as a hard-hitting tackle on the football team and a championship wrestler.

Cavalry

Following graduation in 1912, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the Cavalry and served three years with the 8th Cavalry in the Philippines, then 1 1/2 years with the 17th Cavalry out of Fort Bliss, TX, patrolling the Mexican border during the Punitive Expedition. Captain Littlejohn returned to his alma mater as an instructor in 1917, just three months after the U.S. declared war on Germany.

He switched from Cavalry to Infantry in Spring 1918, was promoted to major and eventually took command of the 332d Machine Gun Battalion at Camp Wadsworth, NY. He set sail for France in September as commander of the 332d. There he served with the 39th and 4th Infantry Divisions in the last days of the war, and for a few months during the occupation that followed.

Littlejohn got his initial exposure to quartermastering while still in the Cavalry, with an occasional stint as Squadron Quartermaster. Just before returning home in 1919, he was detailed to the Quartermaster Corps in France which marked the start of a 25-year association (and, in effect, professional love affair) with the Quartermaster Corps.

Army Food Expert

He graduated from the Quartermaster Subsistence School in Chicago in 1922. He stayed on first as an instructor and then as assistant commandant for nearly three years, becoming something of an expert on Army food and nutrition. Between 1925 and 1930, he graduated from both the Command and General Staff College and the Army War College and taught logistics at Leavenworth, KS for nearly three years.

He spent 1930-35 in the Operations and Training Branch, on the War Department General Staff, before returning for a third tour at West Point, this time serving as Post Quartermaster with the rank of lieutenant colonel. The end of the decade (1938-40) found him back overseas in the Philippines, first as Assistant Quartermaster in Manila, and later as Superintendent of Army Transport Service for the entire Philippines Department.

With the fall of France in 1940, Littlejohn was recalled to Washington to head the Clothing and Equipment Division, Office of the Quartermaster General. There he demonstrated some of the traits that would become his trademark later on: namely, an overwhelming impatience with bureaucratic red tape and a willingness to side-step “niggling regulations” and get out on a legal limb, if need be, to get the job done. By now, too, he had acquired as much logistical knowledge and firsthand experience as any Quartermaster officer in the Army-and he knew it.

With the attack on Pearl Harbor, Littlejohn yearned to get out from behind a desk and take on a field command. As he later explained: “My personal ambition was always to be Chief Quartermaster in a combat theater in a major war. After two years in the Office of the Quartermaster General at Buzzard’s Point, pushing papers and being harassed, I decided it was time to break loose. It was early May 1942 and Dwight D. “Ike” Eisenhower, a fellow West Pointer, had just come to Washington as a newly promoted brigadier general, fresh from the Carolina maneuvers. Littlejohn (also a brand new brigadier general) explained the situation to Ike over a lunch at the Federal Reserve cafeteria, and asked if there was anything he could do. A week later he received a call about becoming Theater Quartermaster.

Chief Quartermaster

Littlejohn arrived in London at the beginning of June and opened an office at Number 1, Great Cumberland. His assigned building had been badly bombed and was bereft of furnishings and equipment. As he described it, he and his lone assistant, Colonel Michael H. Zwicker, pulled together a few cracker boxes to use as desks, and stuck on the door a penciled sign that read “Chief Quartermaster, ETO” (European Theater of Operations). From such humble origins grew a massive enterprise which in the end would affect the fate of millions.

It was known from the start that Quartermaster support would play a vital role in the Allies’ ability to win on the continent, but that it would be a most difficult undertaking. Several factors made it so. Certainly the level of troops, supplies and equipment needed to launch and sustain the cross channel attack dwarfed any previous experience in recent history. Also, the changed nature of mechanized, highly mobile warfare meant that Quartermaster planning factors and reference data had to be worked out almost from scratch, and amounted to little more than educated guesswork.

Another factor was organization. The complicated support structure that emerged between 1942 and 1944, and continued changing even to the end of the war, was built on tension, compromise and often conflicting or overlapping lines of authority. A logistics flow chart would show theater supplies moving through communications zone, from base section to advance section, with a host of intermediate depots, storage areas and distribution points-to get to user units at the front. Of course, this all took place at the end of a very long line of communications, with a zone of interior and industrial base nearly 3,000 miles away.

Also, a large number of technically trained units and personnel-more than 30 different Quartermaster units alone, ranging from supply depot and railhead companies, to very specialized bakery, salvage, refrigeration, shoe repair, petroleum distribution, and graves registration units, to name but a few-were required to sustain Allied soldiers in the assault.

Logisticians of every stripe had also to contend with the vagaries of coalition warfare. In Littlejohn’s case, he relied heavily on his British hosts for such crucial items as assigned storage facilities, laborers and clerical help, and a tremendous amount of locally procured goods and services. Their dealings were usually, but not always, amicable. In time, most of the frustrations were overcome as coalition partners learned to adjust to one another’s standards and practices.

Yet, in war, as Clausewitz said long ago, even the simplest thing is complex. Hence it took time for procurement officers to learn, for example. that when our English-speaking counterparts said “bracers” what they really meant was suspenders, that garbage cans were called “dust bins,” and that cookies in the United Kingdom were termed “biscuits.” And so on and so forth.

For Littlejohn, each day brought a fresh set of challenges and new problems that needed solving. And not a few surprises. After several months of painstaking efforts to accumulate Quartermaster support for the crosschannel invasion, suddenly in late Autumn 1942 he was given the word to refocus Quartermaster planning, resources, men and materiel in anticipation of Operation Torch. This sudden shift in strategic priorities marked an immediate setback for the Chief Quartermaster. He sent 78 of his best officers to North Africa while others were taken from his replacement depot at Lichfleld, and from a number of hand picked specialists awaiting shipment at the New York port.

Positive Side

On the positive side, he quickly learned from this experience what worked and what did not, and gained a far-better appreciation of the level of supplies needed to support an over the-beach operation. In comparison with Normandy, Operation Torch was a relatively modest affair. Yet it still required, for instance, 22 million pounds of food, 38 million pounds of clothing, and 10 million gallons of gasoline to be put ashore on the African coastline.

It also illustrated the need for flexibility in every aspect of Quartermaster support-a fact clearly borne out 1 1/2 years later as the continental invasion finally got underway, and Littlejohn and company were made to adapt to the twists and turns, and ups and downs brought on by each season, each phase in the European campaign. Littlejohn was promoted to major general six months before D-Day, June 6, 1944.

Over the Beach

After a successful landing on D-Day, a stalled drive inland and failure to capture port facilities right away meant that Quartermaster supply soldiers had to continue bringing material in over the beach: sort, store and distribute it along a fairly narrow and dangerous front. If Littlejohn felt good about the initial landing, he was none the less surprised by the effects of strenuous fighting in the Normandy hedgerows.

In a matter of weeks, U.S. troops slugging it out in the mud consumed roughly 2 1/2 times the amount of clothing and other Quartermaster items of equipment that he and his staff had planned for. “The capture of each hedgerow meant a life and death race,” he noted afterwards; and in trimming down to meet that race, the American soldier “frequently left behind his overcoat, overshoes, blanket and shelter.” As a result, Littlejohn had to completely re-equip the better part of a million soldiers while still in the early stages of the campaign.

The breakout and pursuit that followed only intensified pressure on the Chief Quartermaster, who saw the overall supply picture go from feast to famine. The situation in late summer and early Autumn 1944 illustrated the old adage that a stationary front is the Quartermaster’s dream come true, while a war of unchecked maneuver poses as the ultimate nightmare. By September the Allies were required to deliver to forward areas no less than 20,000 tons of supplies daily. As the lines stretched further and further from Cherbourg, the inevitable shortages began to be felt-with crippling effect. Whether it could have been otherwise is debatable.

Letters from Littlejohn to a colleague in mid-September give some indication of the trials faced during this period of “frantic resupply:”

“It is very difficult,” he wrote, “to sit here and determine current requirements on clothing and equipage. We know that the Maintenance Factors on many items are entirely too low. We also hope that the war will come to an end before many weeks and it will not be necessary to ship troops as originally planned. Somewhere in the field I must make an educated guess.”

[And again a couple of days later.] “I have so many problems today in connection with clothing that it is hard to know just where to stop or start…”

[Thinking of the future he added.] “I have just returned from talking to General Bradley and I can assure you that for the next 6/8 weeks the problems that I shall have in connection with the mobile ground elements will be something to write about and study at Leavenworth for years to come.”

Of course the war did not end as hoped, and his troubles would persist for another season and more. There was an especially tenuous period during the Bulge when supply lines and key Quartermaster depots came perilously close to enemy capture. But the worst threat came from the weather. The wet winter months took a terrible toll on Allied troops, and Littlejohn’s personnel strained to meet the ever growing demand for winter field jackets, shelter halves, wool blankets, socks, overshoes and shoepacs.

As the number of instances of severe frostbite and trench foot mounted into the thousands, sources inside and outside the military looked for a scapegoat. Littlejohn emerged as a prime target for criticism. It all came to a head in one devastating piece in The Washington Post entitled “Shades of Valley Forge.” Later investigations exonerated Littlejohn of any form of negligence or wrongdoing, but it was a painful episode nonetheless.

Unforeseen

In Littlejohn’s mind all the factors mentioned so far-the dynamics of the campaign, the war’s extension through the winter, high maintenance factors, delays, shortages, and all the rest-contributed to what he saw as the most difficult problem in the ETO, a host of “unforeseen requirements.”

Perhaps the greatest unforeseen requirement of all was the swelling tide of prisoners of war (POWs) who had to be cared for in the waning months of the war. On this subject the Chief Quartermaster later observed as follows:

“Somewhere in the planning for the war against Germany I saw a statement that one million prisoners would be a reasonable estimate of the take. With all my problems of providing for U.S. forces, French forces, and Allied forces I put this problem in the realm of Limbo.”

“It did not remain in that state very long as the victorious American Armies advanced from the west and south the prisoner take reached astronomical figures-as of VE-Day 3 1/4 million.”

Such gross miscalculation resulted in a sorely taxed supply system by war’s end. Littlejohn’s efforts to employ POW labor worked to some extent, but had little effect on the problem overall.

It is perhaps useful at this time to say a few words about Littlejohn’s method or approach to the position of Chief Quartermaster in the ETO. His first, most pressing task was to gather the personnel needed to accomplish the mission. He estimated he spent at least 50 percent of his time that first year in the United Kingdom making or defending tables of organization.

From the few who initially took up residence in the ramshackle London office in June 1942, Littlejohn’s staff gradually increased to 30 or more, then jumped to around 400 or 500, and ultimately ran to more than 1,800 at its peak in February 1945. By then Office of Chief Quartermaster Headquarters had moved to France, and the general himself had become rather comfortably ensconced in a commodious chateau opposite the historic palace at Versailles.

His division chiefs were men of the highest caliber, with wide military background and civilian expertise. He employed, for example, a number of marketing and department store executives, the president of a nationally known shoe company, the manager of a distillery, a college president, and the circulation manager for a major metropolitan newspaper. He also had a habit of rotating his staff fairly frequently so they gained even wider experience.

Great Thrill

Those who failed to measure up were relieved or reassigned, while the successful ones got promoted. Littlejohn had his critics, to be sure, but those who stuck with it to the end remained intensely loyal to “the Old Man.” Many would later look back on these as the most exciting and rewarding days of their lives and had nothing but good things to say about their former boss. A letter from Brigadier General Al Browning, dated 5 Nov 45, is typical in this regard:

“Before I leave the Army, which I expect to do in about two weeks.” he wrote, “I want to tell you how much my association with you has meant to me. It has been a great thrill to watch your operations from the time when I first met you five years ago until now. I don’t know of any man who could have handled the job of Chief Quartermaster for the European Theater of Operations in a manner even approaching the way you did this very vital job.”

“Although you probably will not get proper recognition for what you did,” he continued, “nevertheless several million men were better clothed, housed, and fed because of you.”

But as noted earlier, Littlejohn most definitely had his critics. A rancorous rift developed early on between the Chief Quartermaster and certain elements within the Office of the Quartermaster General (OQMG) back in Washington. They pegged him as a hectoring know-it-all, who constantly hit them up for more of everything, yet pointedly refused to heed their advice. Littlejohn, for his part, did little to disguise his contempt for rear area “academicians” whom he thought knew nothing of soldiering or actual conditions at the front. So a running battle ensued.

When supplies failed to materialize on time or in the amount promised and OQMG’s response was that the check, so to speak, was in the mail and for him to remain patient, Littlejohn was anything but patient. Often as not, he would try an end run by pitching his case through technical channels, hoping to find a more sympathetic ear; or he called the Quartermaster General direct. Transcribed phone conversations have Littlejohn saying over and over, “General, this will not do, it simply will not do!” When this failed he appealed to higher authority, which had the effect of endearing him even less to OQMG. If he persisted in getting the “run-around,” to use his term, he was not above leaking to the press that American GIs were paying needlessly for bureaucratic red tape.

All this would appear more than a little damning unless we realize what truly motivated Littlejohn: the care and well-being of the individual soldier in the field. All else was secondary. Indeed, he was a “muddy boots logistician” who never forgot his World War I experience with shabby clothes and lousy food and vowed it would never happen again, at least not on his watch.

To serve effectively he had to know what was going on. He adopted the practice of routinely sending staff members to the field to gather firsthand evidence, or he went himself to “get a looksee” at how the troops were faring: how their tents were holding up, for instance, or what they thought of the latest rations. Where shortages existed, and whether or not a new item of equipment was being accepted.

It is very tempting to view Littlejohn’s manner and temperament as essentially “Pattonesque.” He told his uniformed personnel in no uncertain terms they were expected to be dedicated, physically fit and ready to sacrifice at all times. He held himself to the same tough standards. Above all, he hoped they would exhibit drive and determination and adopt the can-do attitude needed to overcome the many hurdles that Quartermasters inevitably face in war. Here he harkened to his early West Point days and the words of his old wrestling coach, Tom Jenkins, whose favorite expression was “there ain’t no holt that can’t be broke.” Littlejohn made this the motto of the Quartermaster Service in the ETO, translated into his own language: “It Will Be Done.”

After it was all over, Littlejohn felt tremendous pride at what his team had accomplished. Many thought, and indeed hoped, he would be rewarded for his great service by being picked as the new Quartermaster General. In fact, that honor was bestowed upon another superb logistician, Major General Thomas B. Larkin. Larkin, incidentally, came out of an Engineer instead of the usual Quartermaster background. As a measure of his disappointment, and no doubt reflective of his loyal Confederate roots, Littlejohn once scoffingly referred to the new Quartermaster General as a “Carpetbagger!”

If Littlejohn felt a bit let down and under-appreciated by his beloved Quartermaster Corps in the days immediately after the war, it no ways matched the outright anger and resentment expressed with some of the early histories being written about the war. He completely dismissed a series of monographs on Quartermaster support in the ETO written by historians at Fort Lee, VA. He attacked rather mercilessly Roland Ruppenthal’s second volume on logistics in the “Green Book” series-calling it in effect slanderous, a waste of taxpayer money, and part and parcel of a long-standing conspiracy to, as he put it, “cut my throat.” He even went so far as to call for an inspector general investigation into the matter and asked for a personal audience to discuss it with the Army Chief of Staff. Praise and criticism notwithstanding, Littlejohn got the judgment he valued most from the leaders he most admired: Generals Eisenhower and Patton.

Ike called him “one of the topflight Quartermasters of the world,” and described Quartermaster support in the ETO as “the greatest supply job in history.” Ike thanked him for his invaluable service in an autographed copy of Crusade For Europe.

As for Patton, his and Littlejohn’s respect for each other was complete. Old friends from way back, Littlejohn served as a pallbearer at Patton’s funeral and was later instrumental in having the statue of him erected at West Point. Despite the turmoil of combat, the two managed to stay somewhat in touch throughout the European campaign and apparently enjoyed sharing insights. A few weeks before his fatal crash, Patton wrote in a letter to Littlejohn: “I only wish that we could see more of each other as you and I are among those who look at war from a realistic standpoint.”

Overall, it would seem that Littlejohn’s strong personality aided him in doing the stupendous lob he set out to accomplish. However, his personality probably worked against him in the eyes of posterity, made him appear more Caustic and self-centered than he really was and thus rendered a fair assessment all the more difficult. Indeed it is hard to remain dispassionate toward such a passionate fellow as he.

From my own distant perspective, I tend to side with the wartime appraisal of Colonel Charles Garside, an investigator sent by the Pentagon to check up on some allegations leveled against Littlejohn. In a close-hold report carried back to the states, Colonel Garside came away a fan of the Chief Quartermaster. “I would not want to work for General Littlejohn,” he said, “or serve under him as an officer. I doubt if I would want to go on a camping trip with him. But if I were invading a continent and attempting to destroy a vast military machine I would select Littlejohn as my Quartermaster.”

That’s a judgment I think the general himself would heartily approve.

MAJOR GENERAL R. M. LITTLEJOHN DIES

WASHINGTON, May 8, 1982 – Major General Robert McGowan Littlejohn, retired, who served as General Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Chief Quartermaster in preparing the 1944 invasion of France, died here Thursday of a heart attack. He was 91 years old.

General Eisenhower, who had known his Quartermaster at West Point, gave him the task of seeing that American soldiers went into battle with adequate clothing, footwear and food supplies. Ultimately, his task grew to encompass the needs of two million fighting men.

He received the Distinguished Service Medal and an Oak Leaf Cluster, the Legion of Merit and the Bronze Star.

He was both in Jonesville, South Caroline and graduated from the United States Military Academy in 1912. Before World War I he served in the Philippines, on the Mexican Border and as an instructor at West Point. He commanded a machinegun battalion in France and Germany in 1918-1919.

He retired from the Army in 1956, after which President Truman appointed him War Assets Administrator, a post he held for two years. Among his decorations from Allied Governments were Britain’s Order of the Bath; France’s Croix de Guerre and the Netherlands’ Grand Officer of Orange Nassau.

Among his nearest surviving relatives is a nephew, Colonel James T. Littlejohn of La Grange, Illinois, and two nieces, Mary K. Littlejohn of Clemson, South Carolina, and Mrs., John T. Metcalf of Chevy Chase, Maryland.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard