Jon Edward Swanson was born on May 1, 1942 and joined the Armed Forces while in Denver, Colorado.

He served as an aviator in the United States Army, B Troop, 1ST Battalion, 9th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division, and attained the rank of Captain.

John Edward Swanson was listed as Missing in Action.

The remains of former Boulder resident Captain Jon Swanson were laid to rest Friday morning at Arlington National Cemetery along with his flying partner, Staff Sergeant Larry Harrison, in a ceremony 31 years in the making.

About 75 people, including Army Chief of Staff General Eric Shinseki, attended the funeral at Fort Myer Chapel near the grounds of the cemetery.

Swanson and Harrison’s helicopter was shot down over Cambodia in early 1971 during the Vietnam War, and their remains were only recently recovered. Swanson’s daughter, Brigid Swanson-Jones, was the only person other than the chaplains to speak at short service. She thanked the Army for taking care of its own and never forgetting them, even after three decades.

Swanson-Jones, 33, looked at the flag draped casket holding the remains of both men and said, “Welcome home, Larry. Welcome home, Dad.” Swanson’s widow, Sandee Swanson, said she thought this day would never come. “You go through a year at a time, and after a while you figure that everything that could be done (in finding his body) has been done,” she said. “I never knew people cared so much.”

The procession took a mile-and-a-half trip from the chapel to the gravesite on foot following the caisson drawn by white horses.

Once at the gravesite, the two fallen scout pilots were treated to military honors including a seven-man rifle company firing three volleys, a playing of “Taps” and flag presentations to the families.

Sandee Swanson said the family was told in February the remains had been recovered; however, due to the commingled condition of the bodies, separate burials would not be possible. The Swanson family had no problems with the joint burial, though this is the first time a Medal of Honor winner — which Jon Swanson was posthumously awarded Wednesday by President Bush — has been jointly buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

After 31 years without her husband, Sandee Swanson said the ceremony was tougher than she thought it would be. “It was very hard to make it through the ceremony. I was over come with a lot of different feelings and emotions,” she said.

The entire week, including a trip to the Oval Office, has been an incredible experience for her, she said.

“This was a wonder tribute for a wonderful man,” she said.

Sandee Swanson, joined by her daughters Swanson-Jones and Holly Walker, who now lives in the Washington area, knelt beside the coffin after service had ended to say their final good-byes to a person they had not been able to even say “hello” to in 31 years.

From a press report: 1 May 2002

Thirty-one years late, life is about to come full circle for a Colorado soldier.

Just before he shipped out for his second tour of duty in the Vietnam War, Army Captain Jon E. Swanson, 28, took his wife, Sandee, and their two baby daughters on a trip to Washington, D.C.

At Arlington National Cemetery, they paused at the Tomb of the Unknowns and he explained the significance of thousands of simple, white markers for soldiers who died serving their country.

Within a few months, he met their fate.

His helicopter was shot down on February 26, 1971, in Cambodia. But only now, after an agonizing wait for his family, his remains were finally recovered and are about to come “home” to the nation’s most hallowed ground.

In a White House ceremony today, President Bush will award Captain Swanson with the nation’s highest military honor, the Medal of Honor.

On Friday, his remains and those of his flying partner, Staff Sergeant Larry Harrison of North Carolina, will be buried with honors at Arlington National Cemetery.

To Swanson’s family, it does not mean “closure,” but represents an acknowledgment of the quiet sacrifice so many soldiers made fighting one of the country’s most difficult wars.

“It’s really a part of a healing process for all of us,” said his widow, Sandee Swanson of Boulder. “It’s not only for our family in what we’ve all lost, but it’s for the Vietnam veterans, those souls who served with him, and what they sacrificed.”

Captain Swanson, born in San Antonio, was raised in Denver and settled with his wife and their two young daughters in Boulder before he died.

His love for nature was great. He could name every tree and flower in the mountains west of Denver where his family had a cabin.

If someone told him to go pick up weeds, “He’d say,’There are no weeds — only flowers. They just have different names.’ “

After graduating from Mullen High School in Denver, he went on to study at Colorado State University. There, he enrolled in an ROTC program and during the height of the Vietnam War he followed in the footsteps of his father, a World War II veteran, and joined the Army.

During his first tour of duty in Vietnam, he was shot and wounded on a helicopter mission in May 1967. Later that year, he married Sandee, his teen-age sweetheart, while on leave in Hawaii.

He was eventually transferred to helicopter training duty back in the United States. But by 1970, when the United States was conducting covert operations with the South Vietnamese army in neighboring Cambodia, he volunteered for a second combat tour.

He had only been there a few months when, according to a Department of Defense synopsis, he launched a mission that likely saved many others’ lives — even as he lost his own.

He piloted a small, scout helicopter to fly low and locate targets for better-armed Cobra gunships.

That day, he evaded ground-to-air fire and destroyed five bunkers. But then he spotted a .51-caliber machine gun position and attempted to mark it with a smoke grenade for a Cobra attack.

He circled around to assess the damage and saw the weapon was still intact, with an enemy soldier crawling to man it. He shot and killed the soldier, but soon his helicopter was hit by fire from another machine gun.

Although he was low on ammunition and the helicopter was already “crippled,” he continued the mission to attack the other anti-aircraft position. But soon, the helicopter was hit by more gunfire, exploded in midair and crashed to the ground.

The Department of Defense determined his actions likely prevented “the destruction of many more helicopters and crews.”

For three decades, his remains were never found and returned, even after tense negotiations with Cambodian and painstaking archaeological searches in the 1990s.

It was only this February, after Congress cleared the way for his posthumous Medal of Honor award, that the family learned that a small amount of the Swanson and Harrison remains were finally coming “home” to Arlington.

The family credits Rep. Mark Udall, D-Boulder, Sen. John Warner, R-Va., Sen. Charles Grassley, R-Ia., and the late Rep. Floyd Spence, R-S.C., for helping them win the overdue honors and coordinate them this week.

They’re still amazed at how the posthumous award and discovery of the remains coincided after all these years.

“Believe me, it has been a long 31 years,” said Sandee Swanson, who married Capt. Swanson’s younger brother, Tom. “Why now? Why is all this coming together?”

“I’ve been asking him to tell me why — why is it happening now? What kind of message is he trying to send us?”

His younger daughter, 32-year-old Holly Walker of Fairfax, Va., said it is strange that the father she barely remembers is finally being honored in the middle of the country’s new war.

“This has additional significance because of the war on terrorism,” she said. “Before we commit troops to war, a lot of people say, ‘Is this worth losing a son for?’ I say, ‘Is it worth losing a father for?’ Every time we send our troops in, that’s what I ask.”

Her sister, Brigid Swanson-Jones, 33, of Westminster, said even though she has few memories of her father, he has inspired her to be a quiet leader.

“It’s not really closure because he will always be with us,” Swanson-Jones said. “Instead . . . this means we’re able to bring him home.”

Washington (Army News Service, May 2, 2002) — President George W. Bush honored two soldiers with posthumous Medals of Honor May 1 during a ceremony in the Rose Garden of the White House.

Captain Ben L. Salomon, a dentist, was recognized for his efforts in defending his regimental aid station from a Japanese attack in the Marianas Islands during World War II, and Captain Jon E. Swanson was recognized for his work in marking enemy troop and anti-aircraft positions from a damaged aircraft in Cambodia during the Vietnam War.

Army Secretary Thomas E. White, Army Chief of Staff Eric K. Shinseki and Sergeant Major of the Army Jack L. Tilley inducted both men into the Pentagon Hall of Heroes during a ceremony May 2.

“We gather in tribute to two young men who died long ago in service to America,” Bush said. “In awarding the Medal of Honor to Captain Ben Salomon and Captain Jon Swanson, the United States acknowledges a debt that time has not diminished.”

A dentist by training, Salomon replaced a wounded surgeon in a battalion aid station near the frontlines of the 27th Infantry Division in early July 1944. On July 7, those frontlines were overrun by Japanese troops. After killing several Japanese who entered the aid station, Salomon told everyone in the area to evacuate to the regimental aid station while he held off the attacking troops alone.

Salomon was found dead the next morning holding a machine gun. There were 98 dead Japanese soldiers piled in front of him. He had been hit by enemy fire more than 70 times — 24 of those wounds were inflicted while he was alive, according to an examining doctor.

The doctor’s initial Medal of Honor recommendation was returned without action due to a mistaken opinion that the Geneva Convention forbade the award of valor medals to medical personnel. A much later legal opinion determined that medical personnel may be awarded valor awards for defending their patients, aid station or hospital.

On his second tour in Vietnam, Swanson flew his last mission February 26, 1971, in support of allied ground troops in contact with the enemy in Cambodia. When his CH-6A helicopter ran out of heavy ordnance, was low on fuel and heavily damaged by enemy fire, he continued to mark targets for other attack aircraft using smoke grenades. Swanson’s actions helped destroy five enemy bunkers and three anti-aircraft weapons before his helicopter exploded and crashed into the ground.

Despite recommendations of approval from the chain of command all the way up to the then-serving chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Executive Office declined to award Swanson the Medal of Honor in 1971. Instead, he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. A recent review of the case made it clear that the Medal of Honor was warranted, Bush said.

Swanson’s remains, and that of his gunner, Staff Sgt. Larry Harrison, were only recently returned to the United States, said Chief Warrant Officer 4 Andrew Swanson, who attended both the White House and Pentagon ceremonies in honor of his brother.

“The recovery team visited the crash site five times to bring back all of the remains,” Andrew said. “We knew in 1999 that he had been found because dental records identified some of recovered teeth as his gunner’s.”

Despite many DNA tests, most of the recovered bones could not be positively identified as they were severely burned, Andrew said. Due to the lack of identification, the remains of Swanson and Harrison will be interned together in a group grave May 3 in Arlington National Cemetery.

“It is appropriate that we honor Ben Salomon and Jon Swanson in Washington (D.C.) because it is here in our nation’s capitol — in granite, marble and stone — we remember our nation’s heroes,” White said during the Pentagon ceremony. “(The Hall of Heroes) has no associate members, no honorary members. Rank or political clout cannot get you in. Membership is only for certified heroes.”

President Presents Congressional Medals of Honor

Remarks by the President at Presentation of Medal of Honor

The Rose Garden

1 May 2002- 2:11 P.M. EDT

THE PRESIDENT: Good afternoon, and welcome to the White House, and welcome to our beautiful Rose Garden. We gather in tribute to two young men who died long ago in the service to America. In awarding the Medal of Honor to Captain Ben Salomon and Captain Jon Swanson, the United States acknowledges a debt that time has not diminished.

It’s my honor to welcome to the Rose Garden the Secretary of Veterans Affairs Tony Principi, Secretary Tom White of the Army, General Eric Shinseki, General John Jumper, Brigadier General David Hicks, the Chaplain — thank you General Hicks for your prayer — Congressman Brad Sherman, Congressman Charlie Norwood, Congressman Mark Udall, World War II veterans, Vietnam veterans, fellow Americans.

Joining us in this ceremony are four men who themselves earned the Medal of Honor: Barney Barnum, Al Rascon, Ryan Thacker, and Nicky Bacon. Thank you all for coming.

President Harry S. Truman said he would rather have earned the Medal of Honor than be the Commander-in-Chief. When you meet a veteran who wears that medal, remember the moment, because you are looking at one of the bravest ever to wear our country’s uniform. We’re honored to welcome these gentlemen.

I’m also pleased to welcome the family of Captain Swanson — Sandee Swanson and their daughters, Holly and Brigid. We’re so glad you all are here. I know how proud you must be of the man you have loved and missed for so many years. And seeing you here today, I know that Jon would be extremely proud.

For Captain Ben Salomon, no living relatives remain to witness this moment. And even though they never met, Captain Salomon is represented today by a true friend, Dr. Robert West. Welcome, sir.

Five years ago, Dr. West was reading about his fellow alumni of the University of Southern California’s Dental School. He came upon the story of Ben Salomon of the class of 1937, who was a surgeon in World War II, and was posthumously nominated for the Medal of Honor. The medal was denied on a technicality. Looking into the matter, Dr. West found that an honest error had occurred, and that Captain Salomon was indeed eligible to receive the Medal of Honor.

He earned it on the day he died, July the 7th, 1944. Captain Salomon was serving in the Marianas Islands as a surgeon, in the 27th infantry division, when his battalion came under ferocious attack by thousands of Japanese soldiers. The American units sustained massive casualties, and the advancing enemy soon descended on Captain Salomon’s aid station. To defend the wounded men in his care, Captain Salomon killed several enemy soldiers who had entered the aid station.

As the advance continued, he ordered comrades to evacuate the tent and carry away the wounded. He went out to face the enemy alone, and was last heard shouting, “I’ll hold them off, until you get them to safety. See you later.”

In the moments that followed, Captain Salomon single-handedly killed 98 enemy soldiers, saving many American lives, but sacrificing his own. As best the Army could tell, he was shot 24 times before he fell, more than 50 times after that. And when they found his body, he was still at his gun.

No one who knew him is with us this afternoon. Yet America will always know Benjamin Lewis Salomon by the citation to be read shortly. It tells of one young man who was the match for 100, a person of true valor who now receives the honor due him from a grateful country.

The Medal of Honor recognizes acts of bravery that no superior could rightly order a soldier to perform. The courage it signifies — gallant, intrepid service at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty — is written forever in the service record of Army Captain Jon Swanson.

A helicopter pilot in the Vietnam War, Captain Swanson flew his last mission on his second tour of duty, on February 26th, 1971, over Cambodia. As Allied forces on the ground came under heavy enemy fire, Captain Swanson was called in to provide close air support. Flying at tree-top level, he found and engaged the enemy, exposing himself to intense fire from the ground. He ran out of heavy ordinance, yet continued to drop smoke grenades to mark other targets for nearby gunships.

Captain Swanson made it back to safety, his ammunition nearly gone, and his Scout helicopter heavily damaged. Had he stayed on the ground, no one would have faulted him. But he had seen more — he had seen that more targets needed marking, to eliminate the danger to the troops on the ground. He volunteered to do the job himself, flying directly into enemy fire, until his helicopter exploded in flight.

Captain Swanson’s actions, said one fellow officer, “were the highest degree of personal bravery and self-sacrifice I have ever witnessed”. Others agreed, and the Medal of Honor was recommended by the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, and by the late Admiral John McCain. However, only the Distinguished Service Cross was awarded, until a recent review of the case made clear that the nation’s highest military honor was in order.

And so today, on what would have been his 60th birthday, the Medal of Honor is presented to the family of Jon Edward Swanson.

The two events we recognize today took place a generation apart, but they represent the same tradition. That tradition of military valor and sacrifice has preserved our country, and continues to this day. Captain Salomon and Captain Swanson never lived to wear this medal, but they will be honored forever in the memory of our country.

And now Commander Reynolds, will you please read the citations.

The President of the United States of America, authorized by Act of Congress, March 3, 1863,

has awarded in the name of The Congress the Medal of Honor to

CAPTAIN JON E. SWANSON

UNITED STATES ARMY

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty:

Captain Jon E. Swanson distinguished himself by acts of bravery on February 26, 1971, while flying an OH-6A aircraft in support of ARVN Task Force 333 in the Kingdom of Cambodia.

With two well-equipped enemy regiments known to be in the area, Captain Swanson was tasked with pinpointing the enemy’s precise positions. Captain Swanson flew at treetop level at a slow airspeed, making his aircraft a vulnerable target. The advancing ARVN unit came under heavy automatic weapons fire from enemy bunkers 100 meters to their front. Exposing his aircraft to enemy anti-aircraft fire, Captain Swanson immediately engaged the enemy bunkers with concussion grenades and machine gun fire. After destroying five bunkers and evading intense ground-to-air fire, he observed a .51 caliber machine gun position. With all his heavy ordnance expended on the bunkers, he did not have sufficient explosives to destroy the position. Consequently, he marked the position with a smoke grenade and directed a Cobra gun ship attack.

After completion of the attack, Captain Swanson found the weapon still intact and an enemy soldier crawling over to man it. He immediately engaged the individual and killed him. During this time, his aircraft sustained several hits from another .51 caliber machine gun. Captain Swanson engaged the position with his aircraft’s weapons, marked the target, and directed a second Cobra gun ship attack.

He volunteered to continue the mission, despite the fact that he was now critically low on ammunition and his aircraft was crippled by enemy fire. As Captain Swanson attempted to fly toward another .51 caliber machine gun position, his aircraft exploded in the air and crashed to the ground, causing his death. Captain Swanson’s courageous actions resulted in at least eight enemy killed and the destruction of three enemy anti-aircraft weapons. Captain Swanson’s extraordinary heroism and devotion to duty are in keeping with the highest traditions of military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

Jon E. Swanson, Captain, Infantry United States Army Troop B, 1st Squadron (Airmobile) 9th Cavalry is awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross for heroism while participating in aerial flight evidenced by voluntary actions above and beyond the call of duty in the Republic of Vietnam.

Captain Swanson distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous action on 4 December 1970 in the Republic of Vietnam. While in a visual reconnaissance mission, Captain Swanson’s aircraft came under intense damaging hostile fire forcing the aircraft to ground.

Having evacuated the crew on another aircraft, Captain Swanson stayed behind and with complete disregard for his own safety, flew the damaged helicopter out of the area. Throughout the flight there was imminent danger of an explosion due to unknown damage. Captain Swanson’s outstanding flying ability and devotion to duty were in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflect great credit upon himself, his unit, and the United States Army.

37 years later, Medal of Honor war hero ‘in our hearts all the time’

Posthumous award was link to past for widow, daughters of Jon Swanson

By Ashleigh Oldland,

Courtesy of The Rocky Mountain News

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

Sandee Swanson is reflected in the case containing her husband’s Medal of Honor. Army Captain Jon Swanson was killed in 1971

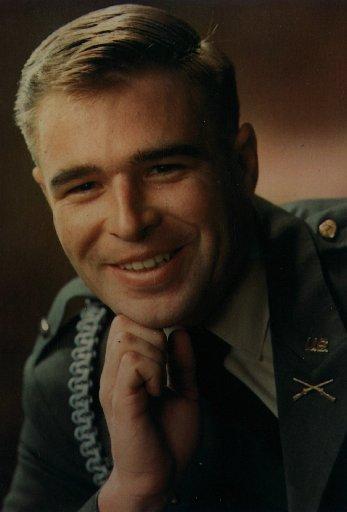

A Vietnam era-photo of Medal of Honor recipient Jon E. Swanson, a helicopter pilot who was killed in battle 37 years ago.

Jon E. Swanson received the Medal of Honor decades after he became a casualty of the Vietnam War.

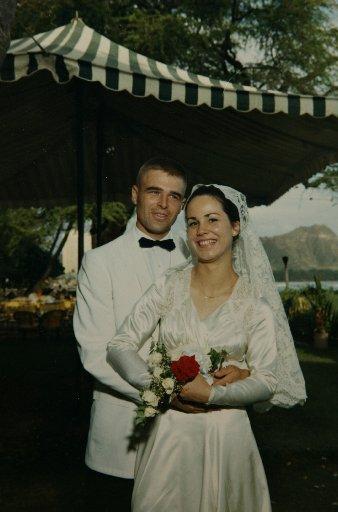

The wedding photo of Jon and Sandee Swanson. The couple married while he was in between military tours.

The Medal of Honor was presented to the Swanson family during a White House ceremony in 2002.

(Swanson Family Photos)

Sandee Swanson’s ache is as fresh as her pride.

Her husband, Capt. Jon E. Swanson, died a war hero in a far-off jungle 37 years ago – a helicopter pilot whose bravery would earn him the nation’s highest military honor.

But for Sandee Swanson, the passage of time hasn’t stopped the churn of her emotions.

“I have a sense of peace, but it’s still raw,” she said. “We carry him in our hearts all the time.”

The Congressional Medal of Honor Society’s annual convention is in Denver this week, and Sandee Swanson has played a role in helping organize the gathering of the nation’s war heroes.

It also has brought back memories – not that they’ve ever gone away – of the high school sweetheart and father of two girls who died far too young as he flew his chopper in Cambodia.

She met Jon Swanson when they were teenagers in Denver. The two occasionally dated but were mostly good friends. Sandee remembers the summers they spent together at the Swansons’ family cabin in Buffalo Creek.

They kept in touch over the next few years. Jon discovered his passion for flying while he studied at Colorado State University and joined the Army ROTC; Sandee joined the Peace Corps and lived in the Philippines.

“We wrote to each other, and he sent me a miniature Christmas tree,” Sandee said. “He used to write things like, ‘I’ll tunnel my way down to the Philippines.’ ”

The couple married in 1967 while Jon took a break during his first tour in Vietnam. She wore her mother’s dress for the ceremony in Honolulu. He wore a rented white tux with a black bow tie because his Army dress uniform was missing an insignia.

Soon, they began a family, settling in Boulder with daughters Brigid and Holly.

But Jon volunteered for a second combat tour in Southeast Asia. On February 26, 1971, he was piloting his OH-6A helicopter just above the treetops during a classified reconnaissance mission over Cambodia. His job: find the locations of enemy positions to support a Vietnamese task force.

Swanson, 28, took out several enemy anti-aircraft positions, then voluntarily returned to target another – even after his lightly armed helicopter was damaged and he ran low on ammunition.

At first, he was reported missing in action, although the Army later determined he and his gunner, Staff Sergeant Larry Harrison, had been killed. Their bodies weren’t found until a recovery mission decades later found their remains. The men were buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

“There is always that doubt – maybe he could have gotten away,” Sandee, 64, said of the long years of not knowing. “When a body is never recovered your mind plays havoc on you.

“The kids were so little they didn’t really know their dad.”

Sandee swung into action from the home front. She raised their two daughters while pursuing a college education at the University of Colorado, majoring in Asian studies. She later went into teaching and now works in real estate.

But the memory of Jon Swanson remained strong for the family. In 1998, spurred by an old card indicating Jon Swanson had been recommended for the Medal of Honor, daughters Brigid Swanson-Jones and Holly Walker began working to get the recommendation reviewed again.

“In 1971, we never knew he had been recommended for the award,” Sandee said. Her daughters’ work netted results: Three decades after his death, in May 2002, Jon Swanson was awarded the Medal of Honor.

Sandee Swanson said she was able to meet men from Jon’s unit for the first time at the White House Medal of Honor ceremony and many have since become as close as family.

“For the guys that served with him, too, that was devastating to them that they couldn’t recover his body,” she said.

This week, Swanson will be a host for the Medal of Honor convention. She said she wants to be there to support others whose spouses didn’t come home.

She says she gained strength from the advice of another widow in her family who told her, “You can’t ever go back. You just have to move forward.”

It took time, but she was able to do that. She married Tom Swanson, Jon’s younger brother, in November 1977.

“We met up at CU in the ’70s and never really dated but were good friends that hit it off,” said Tom Swanson, who formally adopted the two girls.

The couple bought the cabin in Buffalo Creek built by Tom Swanson’s father and grandfather. It’s the place where Sandee spent her high school summers with the Swanson family.

Tom is modest when he talks about his role in helping take care of the family after his brother’s death and about keeping up the cabin in Buffalo Creek.

“He would have done the same or a better job,” he said.

President George W. Bush kisses Sandra Swanson (2nd L), widow of U.S.

Army Captain Jon E. Swanson, after awarding a Medal of Honor posthumously to

him during a ceremony in the Rose Garden of the White House, May 1, 2002.

Swanson’s daughter Brigid Swanson Jones watches.

Sandra Swanson shakes hands with President Bush after she received the Medal of

Honor, which was presented posthumously to her husband Army Capt. Jon E.

Swanson, a Vietnam soldier, in the Rose Garden of the White House, Wednesday,

May, 1, 2002. Swanson’s daughters Brigid Swanson Jones, left, and Holly Walker,

right, also attened the ceremony

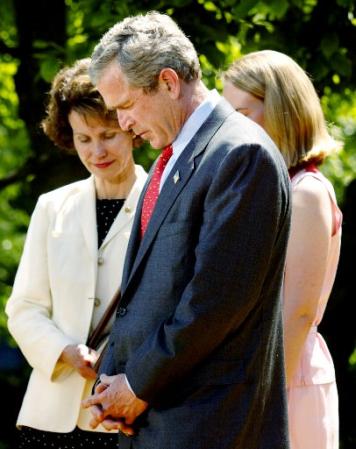

President Bush bows his head in prayer with Sandra Swanson,

who received the Medal of Honor which was presented

posthumously to her late husband Army Captain Jon E. Swanson, a

Vietnam soldier, in the Rose Garden of the White House, Wednesday,

May, 1, 2002. Swanson was flying a CH-6A plane low among the treetops over

Cambodia on Feb. 26, 1971, pinpointing enemy positions, when his plane came under

heavy enemy fire. He responded with machine gun fire and concussion grenades,

destroying five bunkers in a fierce ground-to-air battle. Ultimately his plane exploded

and crashed, killing him. Holly Walker, Swanson’s daughter is at right.

President George W. Bush pauses after awarding a Medal of Honor

posthumously to Sandra Swanson (2nd L), widow of U.S. Army Captain Jon E.

Swanson, during a ceremony in the Rose Garden of the White House, May 1, 2002.

The president also awarded the medal to Dr. Robert West (R), posthumously for

U.S. Army Captain Ben L. Salomon, for his bravery in WWII. Swanson’s daughters,

Brigid Swanson Jones and Holly Walker (C), also attended the ceremony.

Daughter Brigid Swanson Jones, left, has a personal moment with President Bush

after she and her mother, Sandra Swanson, received the Medal of Honor which was

presented posthumously to Army Capt. Jon E. Swanson, a Vietnam soldier, in the

Rose Garden of the White House, Wednesday, May, 1, 2002. Swanson was flying a

CH-6A plane low among the treetops over Cambodia on Feb. 26, 1971, pinpointing

enemy positions, when his plane came under heavy enemy fire. He responded with

machine gun fire and concussiongrenades, destroying five bunkers in a fierce

ground-to-air battle. Ultimately his plane exploded and crashed, killing him.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard