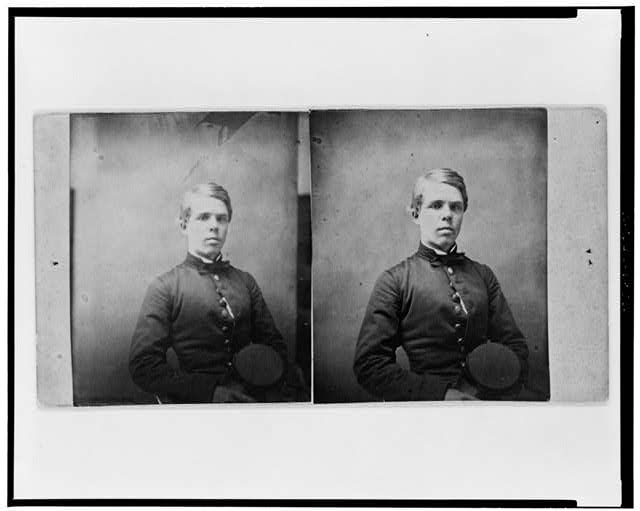

Born in Washington, D.C. on February 9, 1841, he is remembered for the controversy surrounding his death.

The bright elder son of Major General Montgomery Cunningham and Louisa Rodgers Meigs and grandson of United States Navy hero Commodore John Rodgers (see Rodgers family information), he received an appointment to West Point in 1859, took a leave of absence to serve as an aide during First Bull Run, then graduted first in his class of 1863, becoming a Second Lieutenant of Engineers.

After participating in the pursuit of the Confederate Army following the Battle of Gettysburg, he served on the staff of Brigadier General Benjamin Franklin Kelly (Section 1 of Arlington) in West Virginia, he fought at the battle of New Market, Virginia, and campaigned in Major Generals David F. Hunter’s and Philip H. Sheridan’s operations in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.

Sheridan appointed him his Chief Engineer in August 1864 and had him brevetted Captain and Major for gallantry at the battles of Winchester and Fisher’s Hill.

On October 3, 1864, while returning from a surveying assignment with two enlisted men, he overtook three Confederate calverymen on the Swift Run Gap in the Shenandoah and was shot and killed. One enlisted man was taken prisoner and the other escaped and told Sheridan that Meigs, without an opportunity to defend himself, had been killed in cold blood. Believing that Meigs had been murdered by Confederate partisans, Sheridan ordered the town of Dayton, Virginia, burned to the ground. The town was spared however.

Mongtomery Meigs, who remained unconvinced that his son was really a casualty of the war, placed a reward of $1,000 on the killer’s head. The three Confederates who had been involved in the affair gave a more balance version, claiming that the fight had been a fair one. Many such occurences had taken place during the war, but Meigs’ prominence made his case famous.

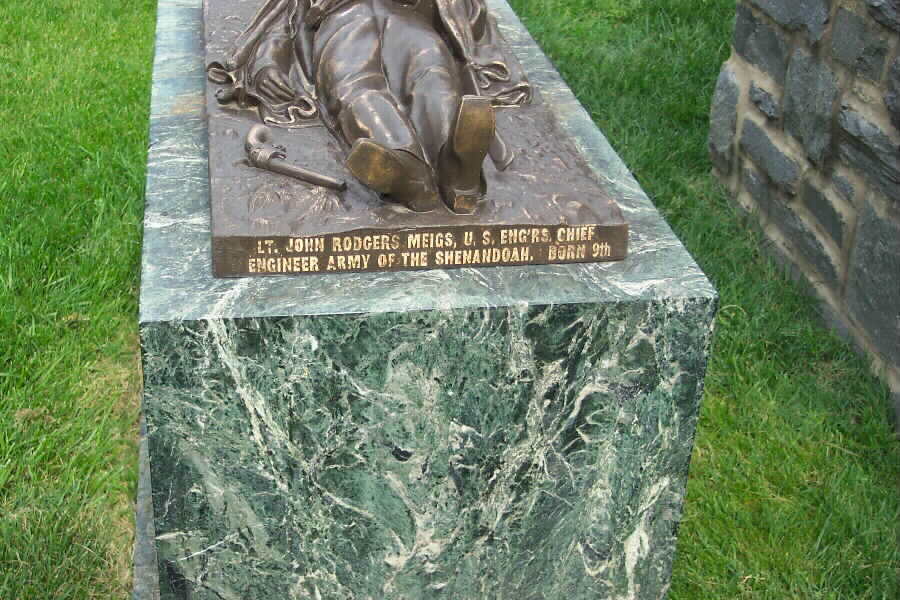

His gravesite in Section 1 of Arlington National Cemetery, is marked with a statue which vividly depicts his death.

MEIGS, JOHN RODGERS

BVT MAJOR US CORPS ENGRS

- VETERAN SERVICE DATES: Unknown

- DATE OF DEATH: 10/03/1864

- DATE OF INTERMENT: Unknown

- BURIED AT: SITE 1

ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

E-Mail: 5 October 2003:

I have just read your website material on Montgomery C. Meigs and his son John Rodgers Meigs. I really enjoyed your material. I imagine 12,000 lieutenants died in the civil war (if 2% of the 620,000 civil war deaths were lieutenants) and quite possibly the one most frequently written of is John Rodgers Meigs. I believe the reason is that the story is so fascinating: a southern family, a father who was quartermaster general of the army, the son’s service on Sheridan’s staff, the burning of a town that nearly resulted from his killing, and, of course, his relationship to the cemetery.

Unfortunately I have noticed in the web site the erroneous claim that the son was killed by guerillas: “In that same year, his son, First Lieutenant John Rodgers Meigs, also a West Point graduate, was killed by Confederate partisans in the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia.”

On the same web page, you actually have the correct information (although contradictory to the above, since it says):

“Stevens writes that Meigs looked on with “grim satisfaction” as they were buried on Lee’s land. Meigs himself would be interred there in a grave near that of his son, killed in action by Confederate soldiers.”

Thus at one point, you refer to “Confederate soldiers” and at another “Confederate partisans.”

On the other hand, the story is more accurately told on your web page devoted to John Rodgers Meigs himself:

“On October 3, 1864, while returning from a surveying assignment with two

enlisted men, he overtook three Confederate calverymen on the Swift Run Gap in the Shenandoah and was shot and killed. One enlisted man was taken prisoner and the other escaped and told Sheridan that Meigs, without an opportunity to defend himself, had been killed in cold blood. Believing that Meigs had been murdered by Confederate partisans, Sheridan ordered the town of Dayton, Virginia, burned to the ground. The town was spared however.”

There is a slight error there: although he was killed on the Swift Run Gap ROAD, the road is probably 50 miles long and the spot of the killing was 21 miles from Swift Run GAP even using straight line distance. The distance on the road is about 35 miles. The importance of this that the spot of the killing was very close to the town of Dayton and, for that reason, the burning of Dayton was ordered. (Had the killing been near the gap, the town of Elkton might have been threatened with burning since it is the closest town to the gap.)

Returning to the issue of partisan vs. soldiers. I invite you to read what I believe is the longest and perhaps most thorough report on the killing: “THE KILLING OF LIEUTENANT MEIGS, 1864” written by Peter Cline Kaylor — article reproduced below — (who happens to be my great-grandfather but I reference him not for that reason but because he was a local historian and was extremely conscious of getting his facts straight). I have attached his paper on the incident. The paper was reprinted in John W. Wayland Virginia Valley Records, Rockingham Supplement; Shenandoah Publishing House, Inc. 1930. , pp 187-96.

You will see in the paper that B. Frank Shaver was the fellow who killed Meigs and, far from being a guerilla or partisan, Shaver was serving with the 1st Virginia Cavalry almost from the beginning of the war. The three confederates possibly were wearing coats or capes over their uniforms at the time (or maybe they had even changed out of their uniforms since they were on a spying mission) but all three were regular confederate soldiers.

Were there confederate partisans operating in the area? Sure. The ones who killed Meigs were regular army, though.

THE KILLING OF LIEUTENANT MEIGS, 1864

Written about 1925 by Peter Cline Kaylor

In the fall of 1864 Sheridan’s army was encamped around – Harrisonburg and Dayton, having closely followed the retreat of Early’s Confederate forces from Fisher’s Hill. At Harrisonburg Early had left the Valley Pike, on the southeast side, thereby permitting Sheridan’s cavalry to go up the Valley as far as Staunton and Waynesboro unmolested.

Early passed Port Republic and went into camp near Weyer’s Cave and Grottoes, later going to Rockfish Gap near Waynesboro, where he awaited the arrival of the brigades of Kershaw and Rosser from east of the Blue Ridge.

Reinforced by Kershaw and Rosser, Early determined to attack Sheridan. He called a council of his lieutenants and it was decided to send two trusted scouts to Bridgewater to see if it was possible to obtain information of the expected move of Sheridan, and also to locate his position.

On the morning of October 3, 1864, a man from North Carolina named Campbell and one from East Virginia named Martin, members of Rosser’s brigade, were detailed to perform this duty. Inas-much as they were not familiar with the roads in that section, an officer in the 1st Va. said he would get a man that lived there and knew every pig trail to accompany them. Forthwith he sent for B. Frank Shaver, Co. I, 1st Va.

Shaver, born and reared on the farm now owned by Q. G. Kaylor, had little more than reached his majority when Virginia called for troops. He volunteered in the cavalry and developed at once into a fearless and adventurous soldier. He took to scout duty as naturally as a duck takes to water. He was a splendid type of physical manhood – more than six feet in height, of dark complexion, with black hair and beard.

Shaver had never met Martin and Campbell until this trip. When informed of his task he was pleased. He said, “I would like to go home and see the folks and get a good square meal.” He also remarked that he had received a letter from his sister Hannah stating that they had a Federal guard with them, and that he would probably have a Yankee brother-in-law when he returned home. Imagining that this guard had probably spoken to some of the family about the Federal movements and that this would be an ideal place to get information the trio started.

Arriving at Bridgewater and learning nothing of Sheridan’s movements, they decided to go through the picket posts to Shaver’s home, having learned where the several pickets were stationed.

From Bridgewater they came to the home of Squire John Herring, and there Mr. Herring confirmed the fact that there were three picket posts on the road that extends from Dayton to the Mennonite Church on the Valley Pike. One was where the road leaves Dayton; the second was on top of the high hill at the Leedy place; and the third was at the Mennonite Church.

The three scouts decided to go between the picket posts to Shaver’s home; so leaving Mr. Herring’s they went northeast by the Byrd farm (now owned by Sam Will) and by the Grove farm (now the home of Grove Heatwole). They crossed the road that leads from Dayton to the Mennonite Church near the home of Jacob Flory and soon entered a piece of timber which extended the entire distance from Flory’s to the old Swift Run Gap Road. From this wood they had full view of the Warm Springs Pike.

A halt was made at the far edge of the timber, and a close observation of the surrounding country was made. About half a mile to their left (northwest) they saw a picket, stationed where the Swift Run Gap Road leaves the Warm Springs Pike. Apparently no one was between them and this picket. They passed out of the timber through a gap in a new rail fence into the Swift Run Gap Road. Turn-ing to the right (eastward) they started up the hill along the new fence, which extended about a hun-dred yards to the Smith and Wenger corner, with the intention of following the road until it turned north. Here they would leave it and go due east through the timber to the top of the high hill west of the Shaver home.

A few moments after coming out into the road they were surprised by three Federals, who came up from under the hill at the point where the said road (old Swift Run Gap Road) is now crossed by the Chesapeake-Western Railroad. The three scouts would gladly have ridden on, but the Federals came up in a gallop calling on them to halt.

Shaver, Martin, and Campbell continued in a walk, and agreed to fight it out if the Federals rushed them before they came to the end of the new fence. Seeing that they would be overtaken before they could make a dash for the timber, they drew their pistols. The Federals were now upon them. The scouts wheeled their horses and commenced firing. The little battle was soon over, and a Federal officer, Lieut. John Rodgers Meigs, of Sheridan’s staff, lay dead in the road, about one-half mile from the Warm Springs Pike. One Federal soldier was captured. The other made his escape by jumping off his horse, climbing the fence, and running into the timber.

The only Confederate injured was Martin, who was shot through the groin. He was about to fall from his horse, but was caught by Campbell. He implored his comrades to take him out of the Fed-eral lines at once, fearing the consequences if caught there.

The Federal prisoner was soon relieved of his weapons, given Meig’s horse to lead, and ordered to keep his mouth shut. The little party galloped back down the Swift Run Gap Road (the same road that Meigs had come up) and crossed the Warm Springs Pike into the woods. The picket stationed there did not realize the situation until the little party was past and in the wood, going west as fast as their horses could take them. The picket then fired but without effect.

When the scouts were near the Abe Paul home (north of Dayton) Shaver and Campbell removed the pistol belt from around Martin and decided to leave him at the home of Robert Wright near Spring Creek. There Dr. T. H. B. Brown of Bridgewater rendered him medical attention. Shaver and Camp-bell returned with their prisoner to the camp of the 1st Va. near Milnesville (now Centerville); and Campbell, leaving Shaver and their prisoner, went on to Rosser’s camp, near Burketown.

The Federal soldier that made his escape, not knowing that his opponents in the fight were Confed-erate soldiers, because they were wearing raincoats or capes, reported to Sheridan’s headquarters that Lieut. Meigs had been shot by citizens.

To administer a gentle rebuke to the neighborhood, Sheridan ordered that the houses and barns that did not have a Federal guard and the town of Dayton should be burned. The torch was at once ap-plied to a number of houses, thereby creating what is known as the “Burnt District.” It is thus re-ferred to by Gov. O’Ferrall in his book, “Forty Years of Active Service,” page 128.

Among those who lost their homes in the “Burnt District” were Daniel Garber, Mrs. Catherine Miller, Jonas Blosser, William Shaver, George Hall, Selima Sunafrank, Benj. Wenger, Abraham Blosser, Reuben Swope, Mike Harshberger, Noah Wenger (barn only, the fire at the house having been put out), Joe Harshberger, Nevel Rogers (this was the Judge Smith place, a large brick house, with mahogany doors), Rev. John Flory, John Herring, Esq., Mrs. Sophia Groves (two dwelling houses, barn, and all outbuildings), Michael Shenk, William Byrd and son, Abe Garber, David A. Heatwole (barn), Abraham Paul (barn), and Joseph Coffman (barn).

The following day residents of Dayton were warned of the impending destruction and moved their property and families into the surrounding lots and fields, where they spent the night, waiting to see their homes go up in flames. In the meantime news of the burnings that took place the same evening that Meigs was killed and the information that Dayton was to be destroyed as soon as the women, children, and old men were moved out, had reached the Confederate forces.

The late T. H. Sandy, at that time a young man and a Confederate soldier, was at the home of his father, William Sandy near Friedens Church, badly wounded in both legs, but beginning to use crutches, when some Yankees came and took two horses from the field and threatened to take him prisoner, but he begged off. That night his father came home from up near Sangerville at about mid-night on his best horse.

T. R. told him that the Yankees would surely take the horse in the morning and would probably take him also, so the family agreed it would be best for T. R. to take the horse and leave that night, which he did. He took with him his brother George, a boy of about 12, to open fences and gates as far as Stemphleytown.

He had to go across country, through fields and woods, because every road had picket posts. These had to be dodged. His father had informed him where the pickets were. In order to reach a ford in Cook’s Creek just below Dayton, on the Joseph Coffman farm, he had to pass by the residence. Grazing around the yard were a number of Federal cavalry horses, loose, but saddled and bridled. The noise made by these horses enabled him to get by with his horse without being detected. He crossed the ford and reached Stemphleytown without being molested. There he left his brother George with his uncle, David Snell.

By this time it was three o’clock. The night was dark and drizzly. He went on from Stemphleytown to Dry River. There he ran into a picket post, with camp fire burning low, He walked his horse very slowly until just opposite. Then the picket discovered him and called “Halt!” He then put his horse into a run up the river and through the Shickel ford. He was now outside of Sheridan’s picket lines and had no more trouble.

Daylight found him near Ottobine, at the camp of the late Hiram Coffman, refugeeing with some of his livestock. He called Sandy, asked him where all the fires were towards Dayton (Coffman’s home) and Harrisonburg. On being told that his property was not burned he seemed much pleased. He feared from the blazes seen during the night that his home had been burned.

Leaving Coffman’s camp, Sandy went on to Sangerville, distant 15 or 18 miles from his home, by sunrise. There he met the late William T. Carpenter, who was also refugeeing stock, who wanted to know where the fires were and also where Sandy got the horse he was riding, saying, “Your father and I went down to Perry McCall’s last evening to get a little whiskey, and the old gentleman drank a little too much. He got a quart more and started down the road on that horse. He said he was going home. I thought maybe the Yankees got him. Was he drunk when he got home?”

Sandy said “No, he was hot; for father said the Yankee pickets drank all the whiskey he had with him.”

When Shaver had learned the fate of Dayton, he and some officer of the 1st Va. went to the guard house and asked for the Federal prisoner, who had not yet been sent to Staunton, the railroad point for Libby at Richmond, and asked him whether, if he were paroled, he would go to Sheridan’s head-quarters at Harrisonburg (the home of Abe Byrd) and tell him that Meigs was killed by Confederate soldiers, he answered in the affirmative; was paroled and escorted back towards Bridgewater and the Federal pickets. This man lived up to his word and Sheridan revoked the order to burn Dayton.

I hope these facts will clear up the mystery that so many accounts heretofore published contain as to why Dayton was not burned, and will show also that Lieut. Meigs was not killed by bushwhackers.

The man Martin referred to in the forepart of this account, under the skilful hands of Dr. Brown and his nurses, was soon able to return to his home, but he did not see service again as a soldier. He al-ways claimed that he had killed Meigs. About 1877 he learned that his pistol did not go off when it was aimed at Meigs’s heart. When his pistol and belt were taken off they were placed on Meigs’s white-faced horse and taken into Shaver’s camp. Upon examination, it was found that his pistol con-tained all the loads, but the caps were all burst. Both Martin and Shaver had aimed at Meigs. Camp-bell fired at the soldier that surrendered and at the one that climbed the fence and ran into the woods.

Shaver never saw Martin again after leaving him at Robert Wright’s, nor Campbell after they sepa-rated at Shaver’s camp, until about 1878. Then the three met in Richmond by appointment.

Shaver remained in the army until the surrender. He was paroled, came home, and resumed work on his father’s farm. The general amnesty granted to Confederate soldiers by the Federal government did not apply to him because he, Martin, and Campbell had gone inside the enemy’s lines at the time Lieut. Meigs was killed; so they were considered as spies.

Accordingly, between the time of Lee’s surrender at Appomattox and the reorganization of the state government of Virginia by Virginians, Shaver had several narrow escapes from the attempts made to capture him. One of the closest that I now recall occurred in this wise. One day a friend of his (I think it was Dr. J. N. Gordon) was in a barber shop in Harrisonburg, with one side of his face shaved, when in walked a Yankee soldier and inquired where Shaver lived. Mistrusting that the day was not healthy for Shaver, his friend asked the barber to excuse him for a moment. He stepped out the back door, hurried to a place where he had recently seen Mr. Levi Shaver, Frank’s father, and told him the situation. Mr. Shaver forthwith mounted his horse and hurried home. He found Frank plow-ing, and told him to get out of the way.

Frank unhitched his horses, went to the barn, clapped saddle on a horse, and rode off. As he was going over the hill near where Frank Miller now lives, the Yankees turned in at the lane towards the Shaver home. At that time the lane left the Pike almost opposite the site now occupied by the Kaylor Park Garage, and led by the barn to the residence.

When the troopers rode up Mr. Shaver went out; and, in answer to their inquiry, he replied, “Yes, Frank is around somewhere. Get down, gentlemen; he will be in in a few minutes.”

He then invited them into the house to have some cider and ginger cakes. They accepted the invita-tion and had a fair sample of “Virginia hospitality”; but all this time Frank was rapidly putting space between himself and the vainly waiting Blue-coats.

In March, 1875, my father, the late Louis W. Kaylor, bought the Levi Shaver borne, where Frank Shaver was born and reared. I was 18 years old at the time. Frank married a Miss Byerly, daughter of his nearest neighbor, who lived where Frank Miller now lives. He was married after the war, and then lived on the Byerly farm. He was our nearest neighbor for a number of years. We often exchanged work on the farm, and frequently talked of the Meigs affair, he personally showed me the spot where Meigs fell. An iron stake now marks the place.

Some time in 1876 or 1877 a cousin of mine, William Shumate, who lived in East Virginia, made us a visit. One night, during a conversation, Cousin William asked my father if a Yankee officer had not been killed in this neighborhood. Father answered “Yes, just over the hill, back of the old house.” Cousin said, “My nearest neighbor killed him.” Father said, “No, my nearest neighbor killed him – a man by the name of Frank Shaver, who was born and raised on this farm.”

Cousin remarked, “Shaver was in the party, but my neighbor, Martin, claims that when he wheeled his horse around it put him in position to put his pistol against Meigs’s breast, and when he fired Meigs fell from his horse.”

My father, turning to me, said “Pete, tomorrow morning after breakfast you go down and tell Mr. Shaver to come up.”

Well do I remember the errand and the ensuing conversation. Frank came up and father introduced him to Cousin William; and Frank described to him about examining Martin’s pistol and finding the caps burst, but the loads still in it. Cousin Shumate returned home and told Martin that he had run across Shaver and that he (Martin) was under the wrong impression as to the killing of Meigs.

By means of Shumate’s visit to my father Martin got into communication with Shaver; and the three men, Martin, Shaver, and Campbell, met at the state fair in Richmond that fall or the next.

I never saw or heard of any printed account of the killing of Meigs until about ten years ago (1914 or 1915), while I was in the state of Washington. I will make one exception. In 1895 the Harrisonburg paper, in publishing an account of Shaver’s death, made mention of the combat in which Meigs was killed and stated that Shaver was one of those engaged therein.

When I read the account in Dr. Wayland’s history of Rockingham County (see pages 148-150 and 434, 435) I was surprised that there was any question as to why Dayton was not burned. I thought that every one who had ever heard of this occurrence knew that it was not burned because the pa-roled prisoner (Federal) returned to Sheridan and told him that Rebel soldiers had done the killing, and that it was not done by citizens.

Dr. Wayland, on page 149 of his history of Rockingham, publishes a letter from Col. Tschappat of Ohio, who was ordered by Sheridan to burn Dayton. Col. Tschappat says that he had moved all the people out into the fields, when the order was revoked by Sheridan; and says that it was Gen. Thos. F. Wildes who prevailed on Sheridan to rescind the order because of its heart-rending effect upon the men in Col. Tschappat’s regiment, which had been commanded at one time by Gen. Wildes.

This is not a reasonable story, for Wildes was one of Sheridan’s staff and probably was present in consultation with Sheridan when the order was issued; and it is not likely that an officer would ques-tion the acts of a superior just because he did not want a regiment that he had once commanded to carry out a certain order.

Referring again to Dr. Wayland’s history, page 434, he says that Shaver and his companions were planning to get on the high hills between the Warm Springs Pike and the Valley Pike to locate the Federals by their campfires. Shaver could have located the campfires easily enough without going inside the Federal picket lines to do so, from any high point south of the Pike Church.

In Governor O’Ferrall’s “Forty Years of Active Service,” page 128, he says that one of Shaver’s men had fallen from his horse dead, and that Shaver and his remaining man had the two Federal cavalry-men prisoners. O‘Ferrall also states, page 129, that General Sheridan, without stopping to investigate, issued and had executed his unjustifiable and cruel order.

The Harrisonburg Daily News of December 12, 1911, contained an article written by Capt. Foxhall Daingerfield and his wife, of Kentucky. They at one time were residents of Harrisonburg. This was a two-column article in which the facts were glaringly misrepresented. The statements cannot he veri-fied, with two exceptions. These are that Lieut. Meigs was killed; and that the white-faced horse that was taken at the time of the killing was frequently seen after the war. Captain Daingerfield says: “Three young men went to the home of a Mr. Shaver and had their haversacks filled and were watch-ing their chance to cross the road and reach the ford by which they could return to camp, when they were charged by Meigs.” This is not a plausible story, for it is at least three miles to the river. He fur-ther states, in the same paragraph, that the house at which the young Confederates had obtained food was one of the first reduced to ashes. This house was not burned, and is now the residence of Q. G. Kaylor.

Again the captain says: “The beautiful and hospitable home of Mr. John Herring was destroyed, the infuriated executioners of a dastardly order throwing back into the flames the cradle of a tiny baby against the pleadings of the mother, and all because in a great war six gallant soldiers had met in a fair and equal combat, in which two were killed and one wounded.”

I am compelled to say that the great historian Joesphus was right when he wrote: “Some people write to show their skill in composition and that they therein acquire a reputation for speaking finely.”

Sheridan was aware of the fact that there was a very bitter feeling in this neighborhood between the Confederate sympathizers and those who were opposed to war, or were Union sympathizers. The lives of the latter in some cases were in danger, and they had been threatened. Rev. John Kline was bushwhacked near Broadway on account of this bitter feeling. Sheridan had agreed to furnish one team and wagon to each Union sympathizer to transport his belongings and family beyond the boundaries of the Confederacy. In fact, the very day that Meigs was killed a number of persons, whose property was burned, had already loaded what they could take on one wagon and had moved as far as Harrisonburg. Among those that I can now recall were Florys, Sunafranks, Thomases, Halls, Blossers, Hinegardners, and some of the Wengers.

Noah Wenger owned the farm where John Dan Wenger now lives. It is near where Meigs fell. His barn was burned the same evening the conflict occurred. Mrs. Wenger was baking and getting ready to leave her home for an unknown destination, and Federal soldiers were encamped all about the premises. Some of them were not as polite as dancing masters, for they would go in where the cakes and pies were and help themselves. She or Mr. Wenger made complaint to an officer, and a guard was immediately put at the house. That evening Mr. Wenger and his family took what they could carry on one wagon and moved out.

When the party that did the burning arrived at the Wenger place they found there Andrew Thomp-son, now a well known resident of Harrisonburg. In 1864 he was a boy of 13, and made his home with Mr. Wenger part of the time. His mother lived in Dayton, and Andy, as his friends called him, had not come home-he was still at Mr. Wenger’s. The Yankees went to the barn and took a portion of the hay that was therein. Then they tore off weather-boarding arid broke it into small pieces to kindle the fire that consumed the building. It was raining that afternoon. Then they mounted their horses arid rode away.

Another squad of Yankees came up to the house. They took the straw that had been emptied from the chaff ticks, piled it against a wooden partition and set fire to it. Andy Thompson then took a crock off of the paling fence (tile buckets had been moved with the wagon), carried water, and put the fire out. This house was standing when Mr. Wenger returned home after the war. Andy was not molested by the soldiers who were at hand when he put the fire out.

About a mile down Cook’s Creek from Dayton is the Squire Herring farm. Across the creek opposite the farm residence was a tenant house occupied by the late Valentine Bolton, who was then in the Confederate army. Mrs. Bolton was told to move out, that the house was to be burned. Some of the Federal soldiers were helping to remove the property when one of them picked up a Masonic man-ual. Turning to Mrs. Bolton he asked, “Is your husband a Mason?” She, feeling somewhat bitter at having the house burned, answered in no pleasant humor, “Yes, he is.” Forthwith the men were or-dered out of the house, and the property that had been removed was immediately replaced. A guard was left there. This house is standing today.

These same soldiers hurried the main residence across the creek at the Herring farm, and this is the house that Captain Daingerfield speaks of, telling of the baby’s cradle in connection. This story seems doubtful, in view of the conduct of the same men at the Bolton home.

At the borne of Joel Flory, father of Jacob Flory, east of Dayton, on the Pike Church Road, old Aunt Betsy Whitmore was lying bedfast at the time the Yankees came to burn the house. After learning the condition of Aunt Betsy they went off and did no burning. A similar situation was found at Abraham Paul’s, where the barn was burned, but not the residence, because in the latter was a sick woman (a Miss Paul).

The evening Dayton was to be burned (the day after Meigs’s death), the Federal soldiers helped move the household goods from the dwellings into the surrounding fields and lots where it would be out of danger of the fires. That evening, when the order to burn was revoked, it was too late to move back into the houses; so the Federal officer in charge placed guards with each family to protect them from that class of rough-necks that are in all armies.

During the evening a drunken Yankee set fire to old Mr. Burnshire’s straw rick. The soldiers of Col. Tschappat’s regiment, who were protecting the families in the fields, extinguished the flames and punished the incendiary by kicking, beating, and rolling him out into the road.

When Sheridan received orders to destroy the grain and other supplies that were stored in mills and barns, and was carrying out the order by applying the torch the burners came to the Burkholder farm, near Garber’s Church, to destroy the barn, which contained grain. The wind being strong, and blowing towards the residence, they went away and left it, for fear of destroying the house. This oc-curred a few days after the burnings around Dayton, on the death of Meigs. Sheridan began his re-treat and burning down the Valley about October 5.

Destruction of supplies was the object in the general burning, not the destruction of buildings. This was shown at the mill of Gen. Sam Lewis, at Lynnwood. This mill had a large quantity of wheat in it, but news was sent by “grape-vine telegraph” to General Lewis (who was a Union man) that if the grain were taken out before morning the mill would not be burned, He had his son, the late Sen. John F. Lewis, who was then superintendent of Mt. Vernon Iron Works, to send the furnace teams down and haul out the wheat during the night. This mill was not burned. Neither were some other mills and barns that were empty.

Tradition has it that the Yankees went to the Joseph Coffman place, just on the outskirts of Dayton, south, and set the barn on fire; then went to the residence to burn it. There they came across a Ma-sonic apron belonging to Mr. Coffman; and so they did not burn the house. The Coffman place was headquarters of Gen. G. A. Custer. Some think that was the reason why the residence there was not burned.

It is my opinion, however, that the David A. Heatwole barn and the barn on the Joseph Coffman place were burned several days after the killing of Meigs, when Sheridan began his retreat down the Valley. It was at the Joseph Coffman place that T. R. Sandy saw the cavalry horses grazing when he passed there late the night of the destruction in the “Burnt District”; and the barn was standing at two o’clock that night.

Published in John W. Wayland Virginia Valley Records, Rockingham Supplement; Shenandoah Pub-lishing House, Inc. 1930. , pp 187-96

Notes by John W. Wayland – At Arcanum, Ohio, August 19, 1928, a Mrs. Baker, daughter of Abram Koontz, told Mr. P. C. Kaylor that the house of her father, Abram Koontz, near Dayton, Rockingham County, Va., was burned along with the others mentioned on page 189.

Anent the burning around Dayton, and the sparing of certain houses, the following is of interest:

On July 14, 1928, Mrs. Thomas Kille of Harrisonburg, whose old home was at or near Dayton, told me that when the “Yankees” came to the Joseph Coffman place to burn (see above on this page; also Wayland’s history of Rocking-ham County, page 149) Mrs. Coffman met them and said, “I am a first cousin of Abraham Lincoln,” and that this was the reason the Coffman house was not burned.

Mrs. Coffman was Abigail Lincoln, daughter of Lt. Jacob Lincoln; the said Jacob being a brother to Abraham Lin-coln, the President’s grandfather.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard