EWS RELEASES from the United States Department of Defense

No. 660-06 IMMEDIATE RELEASE

DoD Identifies Army Casualty

The Department of Defense announced today the death of a soldier who was supporting Operation Iraqi Freedom.

Sergeant Duane J. Dreasky, 31, of Novi, Michigan, died on July 10, 2006, in the Brooke Army Medical Center, San Antonio, Texas, of injuries sustained when an improvised explosive device detonated near his HMMWV in Habbaniyah, Iraq, on November 21, 2005. Dreasky was assigned to the Army National Guard’s 1st Battalion, 119th Field Artillery, Lansing, Mich.

NOVI, MICHIGAN — A public memorial service will be held Saturday at Walled Lake Western High School’s football field for a Michigan National Guard soldier who died from injuries suffered in Iraq.

Sergeant Duane Dreasky of Novi, who suffered burns over 75 percent of his body during an attack in Iraq, died July 10 in Texas.

“He played on that (Walled Lake football) field, he loved that school and loved the Warriors,” said Mandeline Dreasky, his wife.

Sergeant Dreasky was riding in a Humvee near al-Habbaniyah when it was hit by an improvised explosive device on Nov. 21, 2005.

Dreasky was airlifted out of Iraq and ended up at an Army burn center in San Antonio, where President Bush toured on January 1, 2006. Dreasky tried to salute when Bush entered. His story was featured in The Detroit News on June 30, 2006.

“Duane served honorably and embodied the Army values, especially selfless service and personal courage,” said Major General Thomas G. Cutler, the Adjutant General, Michigan National Guard.

Survivors include his wife, Mandeline; parents, Cheryl and Rodger Dreasky; and sister, Dawn Harvey.

Visitation will be from 3 to 9 p.m. today in the O’Brien/Sullivan Funeral Home, 41555 Grand River, Novi.

A funeral service will be at 11 a.m. Saturday at Walled Lake Western High School Football Stadium, 600 Beck Road, Commerce Township.

Burial will be Tuesday in Arlington National Cemetery.

Memorials can be sent to Duane J. Dreasky Scholarship Fund, P.O. Box 23116, Lansing, MI 48909-3116.

Novi GI succumbs to war injuries

While recovering from severe burns suffered in insurgent attack, Guardsman defied condition to salute visiting Bush.

Michigan Army National Guard Sergeant Duane Dreasky, who suffered burns over 75 percent of his body during an attack in Iraq, died in a Texas military hospital after an eight-month fight for his life.

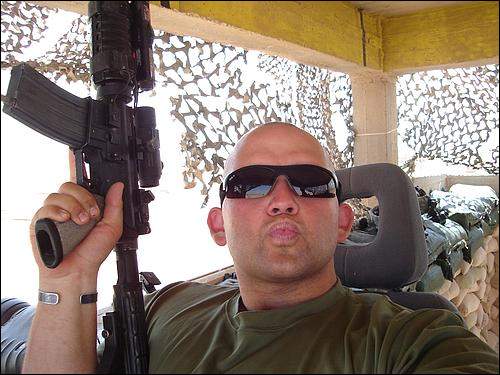

Sgt. Duane Dreasky is shown in Iraq. He was the last survivor of the five-man Humvee unit that was hit by an improvised explosive device Nov. 21.

“He went out with so much dignity,” his wife, Mandeline Dreasky, said Tuesday.

“He fought and defied death four times. We had hoped that he would make it.”

Dreasky, 31, of Novi died Monday at the Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio.

He had been living a life-long dream of serving his country when the Humvee in which he was riding near al-Habbaniyah, Iraq, was hit by an improvised explosive device on November 21, 2005.

He was airlifted out of Iraq and ended up at the San Antonio burn center, where President George W. Bush toured on January 1, 2006, and met with soldiers. Sergeant Dreasky, in bandages, tried to salute when Bush entered the room. The Detroit News featured a photo of Bush and Dreasky along with an article on the front page on June 30.

Dreasky had been recovering at a military hospital in Texas. When President Bush

visited January 1, 2006, he tried to lift a bandaged hand in salute

His death is the 88th from Michigan in the Iraq war, and he is the seventh soldier to die from Michigan Army National Guard Company B, 125th Infantry, based in Saginaw. The unit has suffered the highest number of casualties of any unit from Michigan that has served in Iraq.

He was also the last survivor of the five-man Humvee unit that was attacked on November 20, 2005.

The shock of his death resonated beyond his family.

“He was a big imposing, somewhat intimidating person who loved kids and they loved him,” said Kim Anderson, whose son took martial arts classes from Dreasky.

“He just tried to make his family proud, and he definitely did that.”

In addition to his wife, survivors include his parents, Cheryl and Roger; sister Dawn Marie Harvey; grandmother Virginia Lach; grandparents, Duane and Dorothy Peterson.

Funeral arrangements are pending.

Memorial contributions can be sent to the Duane J. Dreasky Scholarship Foundation, P.O. Box 23116 Lansing, MI 48909-3116.

Debbie Schlussel: Go to This American Hero’s Funeral Saturday (in Detroit Area)

By Debbie Schlussel

Two weeks ago, American hero, Sergeant Duane Dreasky, a brave U.S. soldier and Army National Guardsman, passed away–after 8 valiant months fighting to live.

The Michigan-based man was the last of several U.S. military victims of a terrorist IED targeted at the HumVee in which they were riding. Despite horrible burns over 75% of his body, he tried to salute President Bush when he visited his hospital room and established a scholarship to help others–even though he was in dire straits himself.

Tomorrow (Saturday) Morning is his funeral. Many readers in the Detroit area have asked me if it is a public service, and, indeed, it is. In fact, unfortunately, protesters are reported planning to demonstrate outside. If you live in the Detroit area, I recommend that you attend. The information, from Detroit News reporter Edward Cardenas, is:

Sergeant Duane Dreasky, American Hero, RIP

A public memorial service will be held Saturday at Walled Lake Western High School’s football field for [Duane Dreasky,] a Michigan National Guard soldier who died from injuries suffered in Iraq. Visitation will be from 3 to 9 p.m. today in the O’Brien/Sullivan Funeral Home, 41555 Grand River, Novi.

A funeral service will be at 11 a.m. Saturday at Walled Lake Western High School Football Stadium, 600 Beck Road, Commerce Township.

Burial will be Tuesday in Arlington National Cemetery.

Memorials can be sent to Duane J. Dreasky Scholarship Fund, P.O. Box 23116, Lansing, MI 48909-3116.

Mich. soldiers arrive for comrade’s Arlington burial

Edward L. Cardenas

Courtesy of The Detroit News

ANDREWS AIR FORCE BASE — Dozens of soldiers from Michigan National Guard’s Company B, 125th Infantry touched down this morning in the nation’s capital to honor a fallen comrade from Novi who died July 10, 2006, from injuries suffered in Iraq.

The journey for the burial of Sergeant Duane Dreasky at Arlington National Cemetery was an emotional one for the soldiers.

During their one-year deployment in Iraq, six soldiers from the unit lost their lives, the most of any Michigan National Guard unit. Dreasky became the seventh member to die when he succumbed to injuries he suffered when his Humvee was hit with an improvised explosive device in al-Habbaniyah, Iraq, on November 21, 2005.

The Novi native, who dreamed of becoming a soldier since he was 9 years old, suffered third-degree burns over 75 percent of his body. He clung to life at a Texas military hospital, even managing a handshake when President George W. Bush visited his room in January, but ultimately died of complications from his injury.

Family and friends gathered for his funeral Saturday at Walled Lake Western High School. On Tuesday, his comrades came from across the state to fly in a Michigan Air National Guard C-130 airplane to be with their “brother” and his family one last time. The soldiers landed shortly after 10 a.m. and were headed to a 1 p.m. burial service.

Dreasky is to be buried on the same day Governor Jennifer M. Granholm ordered that United States flags throughout the state of Michigan and on Michigan waters be lowered for one day to honor him.

Soldier Fought for His Life for 8 Months

By Arianne Aryanpur

Courtesy of the Washington Post

For nearly a year after the explosion, Sergeant Duane Dreasky fought for his life and stayed alive — despite the third-degree burns that covered three-quarters of his body.

Every morning, nurses at Brooke Army Medical Center’s burn unit in San Antonio dressed his wounds. In the afternoon, he welcomed visitors: his wife, his family and President Bush, who once toured the facility.

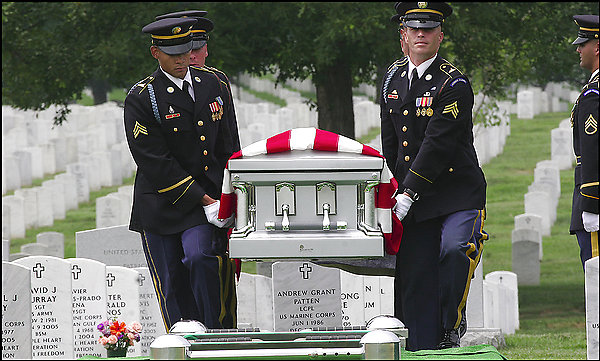

An Army honor guard carries the coffin of Staff Sgt. Duane J. Dreasky, of Novi, Mich., at Arlington National Cemetery

But on July 10, 2006, nearly eight months after he was admitted to the burn center, Dreasky, of Novi, Mich., died of his wounds. He was 31.

Yesterday, mourners gathered at Arlington National Cemetery to honor Dreasky, the 251st person killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried there. A motorcade followed the silver hearse carrying his coffin to Section 60. More than 100 people got out of cars and a chartered bus into the stifling heat. Dreasky’s parents, Cheryl and Roger, and wife Mandeline led the procession to grave site 8407.

A spokeswoman for the medical center said Dreasky was the last surviving soldier of a roadside bomb that exploded near his Humvee in Habbaniyah, Iraq, on November 21, 2006. Four other soldiers in the Humvee died of complications from wounds sustained in the explosion.

Dreasky was assigned to the Army National Guard’s 1st Battalion, 119th Field Artillery, based in Lansing, Michigan. But joining the military wasn’t simple. Because of knee problems, Dreasky had to petition several state officials before he was accepted, the Detroit News reported.

“He definitely was a true patriot,” said Master Sergeant Denice Rankin, a spokeswoman for the Michigan National Guard. “He tried so hard to get into the military to serve his country.”

Shortly after enlisting in 2003, he volunteered to serve in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. He had been back home from that assignment for only four months when he volunteered for Iraq in 2005. Dreasky was deployed with Company B, 1st Battalion, 125th Infantry Regiment.

Over the sound of airplanes and chirping insects yesterday, Army Chaplain Lane Creamer delivered a Protestant service. “Almighty God, we commend Duane into thy loving hands,” Creamer said. Later, a soldier presented an American flag to Dreasky’s wife and another to his parents.

As mourners walked to their cars and Dreasky’s family remained at the grave, the faint sound of a bugler playing taps at another funeral was heard in the distance.

Dreasky was posthumously promoted to Staff Sergeant and received a Bronze Star Medal and Purple Heart. His other awards included an Army Commendation Medal, Army Good Conduct Medal, Iraq Campaign Medal and a Combat Action Badge.

Mandeline Dreasky also served in the Michigan National Guard but was working as a paralegal when her husband was wounded, according to news reports. When Dreasky was admitted to Brooke Army Medical Center, she became a volunteer there and lived on the grounds to be closer to him.

“He went out with so much dignity,” she told the Detroit News this month. “He fought and defied death four times. We had hoped he would make it.”

In hallowed ground: Michigan soldier is laid to rest

Five Michigan Army National Guard soldiers were injured November 21, 2005, in Habbaniyah, Iraq, when an improvised explosive device exploded under the Humvee they were riding in. Specialist John Wilson Dearing died in the explosion. Sergeant Duane Dreasky was the last of the five to die. They were assigned to the 1st Battalion, 125th Infantry Regiment from Saginaw.

Under a gray, cloudy sky on Tuesday, six soldiers carried a silver casket from the hearse to Section 60, Grave 8407, in Arlington National Cemetery — the final resting place of Sergeant Duane Dreasky, who died July 10 from injuries suffered in Iraq.

Mandy Dreasky, his widow, walked slowly behind the casket, followed by more than 100 friends, family and fellow soldiers, including 43 who flew from Lansing on Tuesday morning in a cargo plane.

Dreasky, 31, of Novi, Michigan, was the 10th member of the Michigan Army National Guard to die serving in Iraq. He was the first of them to be buried in Arlington.

Dreasky’s 1st Battalion, Company B, 125th Infantry out of Saginaw was especially hard hit in Iraq, with one of the highest casualty numbers for any Michigan unit in the 3-year-old war. Of the 94 soldiers with Michigan ties who have died, seven were from the 1st Battalion, and five of those were from a single explosion.

“It was overcast and gray at the start, and that’s how I felt,” said Lieutenant Obie Yordy, 35, of Marshall, who served with Dreasky. “But at the end, it kind of lit up and the sun came out. This was an honor. Duane would have cried. I felt guilty that I’m here and he’s not.”

Dreasky was injured Nov. 21, 2005, in Iraq while riding in a Humvee with four other Michigan soldiers. Specialist John Wilson Dearing, 21, was killed instantly.

The other four soldiers were rushed to Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio. They had suffered severe burns and fought valiantly, battling intense pain and countless surgeries — some for weeks, others for months — but none survived.

Sergeant Spencer Akers, 35, of Traverse City died December 8, 2005.

Sergeant Joshua Youmans, 26, of Flushing Township died March 1,2006.

Sergeant Matthew Webber, 23, of Stanwood died April 27, 2006.

Dreasky, who was never told the others had died, was the last one.

“It’s sad,” said Captain Anthony Dennis, who served with Dreasky. “This guy was an American hero.”

Dreasky, who played football at Walled Lake Western High School, joined the Michigan Army National Guard in 2003. He was deployed to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, before he volunteered for duty in Iraq.

Before he left, Dreasky told his mother, Cheryl Dreasky of Novi, that he wanted to be buried at Arlington.

He was buried with honors in an area of the cemetery devoted to soldiers who have died in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Dreasky was the 251st person killed in Operation Iraqi Freedom to be buried at Arlington.

A firing party fired three volleys.

“This is what Duane wanted,” said Major General Tom Cutler of the Michigan Army National Guard. “America just lost an outstanding young person.”

For the soldiers who served with Dreasky and returned home just last month, it was an emotional experience, going to a place several called “hallowed ground.” They spent a few minutes walking the area, snapping pictures and visiting the Tomb of the Unknowns, watching the changing of the guard.

“This is overwhelming,” said Staff Sergant Scott Cortese, 36, of Harrison Township.

Staff Sergeant Rob Witgen, 39, of Williamston served with Dreasky in Cuba and Iraq. Witgen was not surprised when Dreasky fought to live, for so many months, enduring so much pain while showing so much dignity and class. He added that Duane’s wife and parents, Roger and Cheryl, went through hell, trying to nurse him back to health.

“He was the epitome of a soldier,” Witgen said. “He was a fighter. His body gave out before his will.”

As a bugler played taps, the family gathered at the grave site and a helicopter buzzed in the distance. The media was kept in the distance, forbidden to talk to the family.

At the end of the 30-minute ceremony, Mandy Dreasky touched the casket tenderly, while gripping a freshly folded American flag.

Before the family left, four workers lowered the casket into the ground. They rolled up the ceremonial carpet and picked up the chairs on which the family members sat.

The Michigan soldiers filed onto a bus. They were covered with sweat and drying tears. The bus pulled onto a roadway, which led out of the cemetery, where more than 300,000 are buried. The soldiers looked out the windows at thousands of white tombstones, lined in perfect rows. The bus passed another hearse at the side of the road, another grieving family sitting on chairs in front of a casket.

‘He was my brother’

Michigan Guardsmen bury Novi soldier in Arlington

Edward L. Cardenas and Gordon Trowbridge

Courtesy of The Detroit News

Michigan National Guard Brig. Gen. Robert Taylor presents the American flag to Mandeline Dreasky, Staff Sgt. Duane Dreasky’s widow, at the soldier’s funeral. See full image

A bugler plays “Taps” during Dreasky’s funeral, against the backdrop of scores of other fallen soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery. Dreasky received a posthumous promotion to staff sergeant. See full image

Staff Sgt. Scott Cortese ponders the day ahead on the C-130 flight to Dreasky’s funeral. “I’ve never been to Arlington (National Cemetery) before so I know it’s going to be a pretty moving experience,” he said. See full image

On their way to say goodbye to a fallen comrade, aboard a noisy transport plane and later a bus headed to Arlington National Cemetery, they traded stories — not as much about how their friend died, but how he lived.

They remembered Staff Sergeant Duane J. Dreasky’s gung-ho attitude, how he was proud of the sharp, starched lines of his uniform and his spit-shined boots. They chuckled over how he once turned off the hot water to a friend’s shower as a practical joke. How he made a cake out of Twinkies and Ho Hos for a birthday celebration.

Most of all, members of Michigan National Guard Company B, 125th Infantry remembered Dreasky as a fighter — a soldier who battled for eight months before dying July 10, 2006, from burns suffered when a roadside bomb struck his Humvee in Iraq. He was 31.

“Even though I was his leader, he had qualities I wanted to have,” said Staff Sergeant Keenon Wallace, who supervised Dreasky during an earlier deployment to Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. “He wasn’t ‘like’ my brother. He WAS my brother.”

Dreasky, whose National Guard unit has suffered more casualties than any other Michigan Guard unit so far, became a symbol of hope as he struggled to recover, even attempting to salute President George W. Bush during the president’s visit to his room in January.

His story was profiled in The Detroit News on June 30.

Dreasky’s final journey marched past street markers carrying the names of historic giants — Eisenhower, Bradley, Marshall — and stopped, appropriately, on York Drive, named for a simple sergeant who became a hero on a battlefield far from home.

Then, the short walk from a hearse to Section 60, Grave 8407 of Arlington, where Dreasky, who had dreamed from his youth of serving as a soldier, received a soldier’s burial, with rifle volleys fired in salute and the mournful call of “Taps” sounding across neat rows of white headstones.

Dreasky is among 90 Michiganians to die in Iraq, and is the first Michigan National Guard member to be buried at Arlington. There are 251 other U.S. soldiers killed in Iraq who have been buried at Arlington.

He was posthumously promoted to the rank of staff sergeant, and honored Saturday with a memorial service on the football field at his alma mater, Walled Lake Western High School.

His friends and fellow soldiers — about 50 of whom flew to Arlington early Tuesday from Michigan for the funeral — could think of no better place to rest for a man who glowed with pride at being a soldier.

“If I had an army (of soldiers) like him, I wouldn’t have a job to do,” said Sergeant Major Dan Lincoln, whom Dreasky begged for a spot on deployments to Cuba and then to Iraq.

The Michigan soldiers gathered before dawn Tuesday, first at Selfridge Air Force Base in Macomb County to board a C-130 transport plan for a short flight to Lansing, where more boarded, and then for a two-hour flight to Andrews Air Force Base outside Washington, D.C.

Staff Sergeant Tom Barrett, 25, of Kalamazoo became close friends with Dreasky while they roomed together in Cuba.

They knew each other well enough that Dreasky once played a practical joke on Barrett, shutting off the hot water to his shower. And Dreasky made Barrett a Twinkie-and-Ho Ho birthday cake when Barrett turned 23.

“There wasn’t one thing he did poorly as a soldier,” said Barrett. “Here he is, a National Guard soldier who’s supposed to work one weekend a month and two weeks a year, and he would constantly volunteer to serve.”

Others remembered Dreasky’s pride at being a soldier, and the uniform he wore.

“To see his knowledge of the military, you would think he had been a soldier for 15 years, not three,” said Capt. Anthony Dennis, Dreasky’s company commander.

Volunteering had gotten Dreasky into the military in 2003, and to Iraq with Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 125th Infantry Regiment. And it put him on a Humvee near Habbaniyah, Iraq, on November 21, 2005.

Dreasky wasn’t scheduled for the mission, said Sergeant First Class Kevin Nemetz, but he was eager to go. “His enthusiasm and work ethic were unrivaled,” he said.

The soldiers were hoping to set up an ambush for insurgent bomb-makers, but instead, a roadside bomb ripped through a Humvee in their convoy.

Private First Class John Dearing, 21, of Hazel Park died instantly. Three others died in the following months from injuries in the blast – Sergeant Spencer C. Akers, 35, of Traverse City; Sergeant Joshua V. Youmans, 26, of Flushing Township; and Sergeant Matthew A. Webber, 23, of Starwood.

Dreasky fought on despite burns over three-quarters of his body, receiving treatment at Brooke Army Medical Center in San Antonio, Texas, the Army’s top burn center. Nemetz said the company drew encouragement from his battle, even as other soldiers injured in the blast died.

“It was constantly reopening wounds,” Nemetz said. “Then we hung our hats on Dreasky.”

Which brought the soldiers Tuesday to Arlington, on a hill overlooking the Potomac River and Washington in one direction, the Pentagon in another.

They arrived early for the 1 p.m. ceremony, took the short walk to the Tomb of the Unknowns, where they watched the solemn changing of the guard.

Then they walked back to the spot just off York Drive — named for another sergeant, Alvin York, who won a Medal of Honor during World War I.

The men in sharp green uniforms lined up behind Dreasky’s family, listened to the words of an Arlington chaplain drift over the grass: “The Lord is my shepherd, I shall not want.”

Then came the crack of the rifle salute, the playing of “Taps.”

“It puts some closure on that day,” said Dennis, the Bravo Company commander.

“I wish it had a better ending.”

As they walked back to their waiting bus, Dreasky’s widow, Mandeline Dreasky, approached the group, which gathered close to listen. According to Barrett, Mandeline Dreasky told the soldiers she was proud they came and that her husband would have been proud of them. When she had finished speaking, they broke into applause.

Sergeant Duane Dreasky of Novi, Michigan, is buried Tuesday at Arlington National Cemetery. He was injured

with four others in November. 2005. One was killed. The others fought for life, but succumbed

after weeks or months in the hospital. Dreasky, the last of the five, died July 10

Members of the U.S. Army’s Old Guard render honors Tuesday at the burial of Michigan National Guard

Staff Sergeant Duane Dreasky, who died July 10 of complications from wounds sustained while on duty in Iraq.

Dreasky was laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery

The U.S. flag is presented to Dreasky’s widow, Mandy. Seated next to her are his parents, Cheryl and Roger Dreasky.

“This guy was an American hero,” said a soldier who served with Dreasky

Arlington: repository for U.S. war dead

About 300 killed in Iraq alone are now buried there

Perhaps no place illustrates the toll of the Iraq war more vividly than Section 60 of Arlington National Cemetery. In this “garden of stone,” in ruler-straight rows, rest one-tenth of the Iraq war’s American dead, whose number now approaches 3,000.

Privates lie beside officers. Soldiers beside Marines. Muslim troops beside Christians and those of other faiths.

Many were seasoned veterans, but most — 60 per

cent — never reached age 25.

Some died in fierce battles, trading bullets and rockets with a flesh-and-blood foe. But as the insurgency gained momentum in the past year, almost half of the servicemen and women fell to a faceless enemy, victims of remote-detonated IEDs, improvised explosive devices.

Like Army National Guard Sergeant Duane Dreasky of Novi, Michigan.

Each branch of service is represented here, though the Army has taken two-thirds of the Iraq war losses.

There are other grim statistics: More than two dozen fell at age 18; 62 were women; nearly one-quarter of those who died came from just three states, California, Texas and New York, according to casualty figures, which also show recent monthly death totals climbing to levels not seen since the war’s early days.

Each of the fallen resting here on a grassy slope facing the Washington Monument could stand for many others — traditional heroes decorated for acts “above and beyond the call of duty,” and those whose families say their heroism consisted of putting on their country’s uniform during a time of war.

Arlington honors each with a glistening 232-pound Vermont marble headstone marked with the most basic of information — and a number.

Dreasky lies down the row in space No. 8407.

Here is the story behind that number.

Years of football and jiujitsu had taken a toll on Duane Dreasky’s knees. But when the recruiters told him he was ineligible to serve, he bombarded local officials with letters until they finally let him enlist in the Michigan Army National Guard.

Twenty-one percent of those lost in Iraq were in the Guard or Reserve, none more determined than the man known as “Big D.”

When the beefy martial-arts instructor was told that his weight didn’t present “a good image for an NCO,” he went on a crash diet, ran with a 40-pound rucksack and lost about 50 pounds.

Dreasky’s wife, Mandeline, was also in the Guard and was severely injured during a 2003 deployment to Kuwait. But her husband had waited more than 10 years for his chance to serve, and she didn’t stand in his way.

Dreasky begged his way into a 13-month tour at Guantanamo Bay, then almost immediately badgered his superiors into letting him join Bravo Company, 1st Battalion, 125th Infantry Regiment, on its deployment to Iraq. Once there, the 31-year-old sergeant acted more like a new recruit, constantly asking his superiors, “Anything else need to be done, boss?”

And so it was on the morning of November 21, 2005.

A group of eight Humvees was heading out into al-Habbaniyah. Dreasky was supposed to be off duty to give a younger forward observer a chance to learn the ropes, but he managed to pester his weightlifting buddy, Sergeant Matthew Webber, into giving another guy the day off.

As they prepared the vehicles, Dreasky, Webber and Staff Sergeant Michael Haney made plans to meet at the gym after chow for a workout. Before they parted, Dreasky flashed his trademark smile and uttered a favorite line from the movie “Gladiator”: “Strength and honor.”

The day’s mission was to take “atmospherics” in town and to bait insurgents — who’d been sowing the streets with improvised explosive devices — into making a move. They already had.

The Humvees were returning to base after about an hour’s work when two bombs, buried about a foot beneath the road’s surface, exploded. With a muffled WHUMP-WHUMP, Dreasky’s vehicle burst into flames.

Specialist John Dearing died instantly. The remaining four were burned almost beyond recognition. Despite excruciating pain, Dreasky did not cry out. Instead, he was obsessed with finding his rifle, so it wouldn’t be left behind for the enemy.

Dreasky was evacuated with the other wounded. That night, Staff Sergeant Mark “Doc” Russak, the unit’s chief medic, prayed in the camp’s makeshift chapel, then returned to his bunk, where he captured the torment of the moment in his journal.

“I don’t think the men of Bravo could take another death right now,” he wrote, “and I know it would crush me.”

But the deaths would keep coming: Sergeant Spencer Akers in December; Sergeant Joshua Youmans, who never got to hold the daughter born during his deployment, in March; Webber in April.

Dreasky, who was not told of the others’ deaths, battled to recover at San Antonio’s Brooke Army Medical Center.

When President Bush visited there in January, Dreasky moved to salute. Bush lightly touched Dreasky’s bandaged right arm and said: “You don’t need to salute. I need to salute you.”

Finally, on July 10, 2006, the IED of months before claimed its final victim.

The day before he deployed, Easter Sunday, the boy who once got in trouble for wearing camouflage to elementary school, asked his mother to promise him something.

“Mom, this is war. Anything can happen,” Cheryl Dreasky recalls him saying. “If something happens to me, you don’t rest until I’m buried in Arlington.”

After the funeral, when the bugle’s echo had faded and the brass shell casings from the rifle salute were collected, Mandy Dreasky gathered her husband’s comrades around her.

“You all need to continue to be soldiers,” she said. “Because that’s what Duane would have wanted. And that’s what he would have done.”

But some of Dreasky’s comrades wonder if Iraqis truly appreciate the sacrifices being made on their behalf.

“These people, you just see the apathy in them and you’re like, ‘Why am I here?’ You know?” says Staff Sergeant Jeremy Plaxton, who served with Dreasky. “If they don’t want it, I can’t make them accept freedom and fight for it.

“Personally,” he says, “I wouldn’t give up one Dreasky for the entire country of Iraq.”

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard