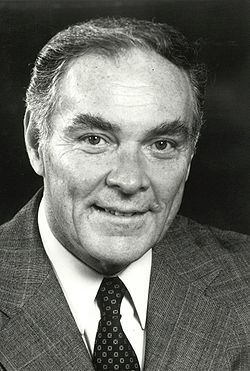

Alexander Haig, 85; soldier-statesman managed Nixon resignation

Retired Army General Alexander Haig, who held influential positions in the U.S. military and government and who as White House chief of staff shepherded Richard M. Nixon toward peacefully resigning the presidency, died Saturday at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore of complications from an infection. He was 85.

In a statement, President Obama said Gen. Haig “exemplified our finest warrior-diplomat tradition of those who dedicate their lives to public service.”

General Haig’s influence peaked in his late 40s, during Nixon’s last 16 months in office, when brewing developments in the Watergate scandal damaged and increasingly distracted the president. Secretary of State Henry Kissinger famously told General Haig to keep the country together while he held the world together during one of the greatest constitutional crises in the nation’s history. Special prosecutor Leon Jaworski, and many others, called General Haig the “37 1/2 president.”

General Haig, untainted by the botched break-in at the Democratic National Committee headquarters, took over as chief of staff in May 1973 from H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, who would spend 18 months in prison for his role in the Watergate scandal. When the public learned about the secret Oval Office taping system, which would eventually implicate Nixon in the coverup, General Haig, as he acknowledged later, urged the president to destroy the tapes.

When Watergate special prosecutor Archibald Cox, Jaworski’s predecessor, pursued his investigation too aggressively for Nixon’s comfort, the president dispatched General Haig in October 1973 to instruct the acting attorney general, William D. Ruckelshaus, to fire Cox. “Your commander in chief has given you an order,” General Haig told him.

Ruckelshaus refused, quitting instead in what became known as the Saturday Night Massacre.

Although General Haig vigorously defended the president, he realized the direness of the mounting evidence and arranged a series of meetings between Nixon, his attorneys and leading members of Congress to make Nixon understand that his position had become untenable in the summer of 1974.

General Haig said he thought Nixon needed to make the final decision, but he “smoothed the way” by presenting resignation as the only serious option, according to the account of this period in journalists Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s 1976 book “The Final Days.” After the president broached the possibility of suicide, the authors noted, General Haig ordered doctors to take away Nixon’s tranquilizers and deny his requests for pills.

Then, on August 1, 1974, General Haig told Vice President Ford that he should prepare to assume the presidency. lritics said later that he brokered a deal that got Nixon a pardon in exchange for stepping down. General Haig maintained that he never implicitly or explicitly made such an offer.

General Haig stood on the White House lawn eight days later, on August 9, when Nixon left town. The chief of staff had his arms folded, but he discreetly gave a thumbs-up to his disgraced boss.

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. was born on December 2, 1924, in the Philadelphia suburb of Bala Cynwyd, Pennsylvania. He was 10 when his father, a lawyer, died of cancer and left the family $5,000 in life insurance money. General Haig was the second of three children, but he assumed an important role in family matters as the oldest male.

From a young age, he aspired to a career in the military. He graduated in 1947 from the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, New York, and graduated 214th in a class of 310. Nevertheless, he advanced far more rapidly than his academic record might have suggested.

After college, he went to Japan to help with the post-World War II occupation. While playing football, he caught the eye of Patricia Fox, the attractive daughter of a general on General Douglas MacArthur’s staff. He married Fox and earned a spot on MacArthur’s staff, though not working directly for his father-in-law.

General Haig is survived by his wife and three children, Alexander, Brian and Barbara; and eight grandchildren.

General Haig was working as MacArthur’s staff duty officer on June 25, 1950, when the North Koreans surged across the 38th parallel. He later claimed that during the Korean War, he carried MacArthur’s sleeping bag ashore during the landing at Inchon. The young officer was in Korea for both the advance to the Yalu River and the withdrawal that followed when the Chinese crossed it.

As his military career progressed, Gen. Haig picked up a master’s degree in international relations from Georgetown University in 1962, and he continued to attract a powerful series of mentors. Then-Army Secretary Cyrus Vance chose General Haig as his military assistant. Joseph Califano, a special assistant to Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara, then tapped General Haig as his deputy.

Staying on the fast track, General Haig took over a brigade in Vietnam as tensions escalated from 1966 to 1967. Shrapnel from an exploding grenade left a scar on his eyebrow, and he received the Purple Heart. Enemy fire downed his helicopter during the battle of Ap Gu, and he survived a successful crash landing. He returned to West Point from 1967 to 1969, where he was a regimental commander before becoming deputy commandant.

Califano was among those who recommended then-Colonel Haig to Kissinger, the incoming national security adviser after Nixon won the presidency in 1968. As military assistant, General Haig prepared daily reports for the new president and acted as a liaison between the Defense and State departments. Long hours and his finely honed skill at bureaucratic infighting helped him make influential friends. In October 1969, after only nine months at the White House, he won a promotion to brigadier general.

From 1969 to 1971, General Haig transmitted 17 requests from the White House to the FBI for wiretaps of reporters and government officials. Among those whose phones he had bugged were the military assistant to the defense secretary and a close personal adviser to the secretary of state.

In January 1972, General Haig led the advance team to China for a top-secret four-day trip that laid the groundwork for Nixon’s historic visit to the communist country the next month. General Haig’s star kept rising in Nixon’s eyes, and his relationship with Kissinger became increasingly fraught with tension. Later that year, General Haig went with Kissinger as the president’s personal emissary to Paris for peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. General Haig persuaded South Vietnam President Nguyen Van Thieu to agree to the January 1973 cease-fire.

General Haig discreetly told the president and Haldeman about Kissinger’s designs for peace when he thought military options hadn’t been exhausted, even showing the pair transcripts of Kissinger’s private telephone conversations, according to historian Robert Dallek.

“Kissinger’s distrust of Haig was well deserved,” Dallek wrote in “Nixon and Kissinger,” his 2007 book. “As ambitious as anyone in the administration, Haig’s hard work and effective manipulation of Nixon, Haldeman, and Kissinger himself had brought him rapid advancement.”

Months later, Nixon promoted General Haig to four-star general and made him the Army’s vice chief of staff. Doing that required the president to bypass 240 generals with more seniority. The promotion sent General Haig back to the Pentagon, but Haldeman’s resignation meant the assignment wouldn’t last long. To take the chief of staff job, General Haig reluctantly retired from the military.

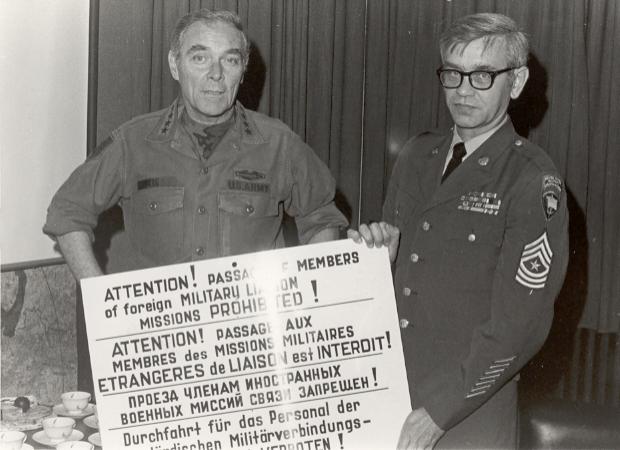

General Haig stayed on as White House chief of staff for the first six weeks of Ford’s presidency. At his request, the new president recalled him to active duty as commander in chief of U.S. forces in Europe. He became supreme allied commander in Europe in December 1974 and worked to strengthen the Atlantic alliance. After Jimmy Carter won the presidency in 1976, he retained General Haig.

In 1979, General Haig retired from the Army and left NATO. The week before he hung up his uniform, a remote-controlled bomb detonated under a bridge in Belgium as his car drove over it. The blast threw General Haig’s Mercedes 600 sedan into the air, but he escaped the assassination attempt without injury. Members of the Red Army Faction, a radical leftist group, were convicted in connection with the attack.

General Haig was president of United Technologies, one of the county’s biggest companies, before being named Ronald Reagan’s secretary of state in 1981. He became the most prominent official from the Nixon administration to return to government, partly as a result of aggressive lobbying by Nixon. Polls showed that important blocs of voters remained nervous that the new president would be a saber-rattling militarist, and General Haig supported seeking a stable balance of power through detente with the Soviet Union.

The ties to Nixon dogged General Haig. Democratic critics forced him to answer tough questions during five strenuous days of confirmation hearings, and liberal columnists opined against his selection.

General Haig got into a testy exchange with then-Senator Paul S. Sarbanes (D-Md.), who pressed him for a “value judgment” about Nixon.

“Nobody has a monopoly on virtue, not even you, Senator,” General Haig retorted.

He acknowledged to the senators that “improper, illegal and immoral” actions had been taken during the Watergate coverup, but he refused to criticize Nixon.

“I cannot bring myself to render judgment on Richard Nixon or, for that matter, Henry Kissinger,” he said. “It is not for me, it is not in me, to render moral judgment on them. I leave that to history, to others and to God.”

The full Senate voted 93 to 6 to confirm him as the 59th secretary of state on the day after Reagan’s inauguration.

General Haig’s 18-month tenure as secretary proved tumultuous, marked by continuing efforts to claim power over foreign policymaking that Reagan and his aides didn’t want to give him. A characteristic first news conference created a maelstrom of bad publicity. General Haig declared himself the “vicar” of foreign policy.

“With the dazzling speed that only words possess, it entered the vocabulary of the press and played its part in creating first the impression, and finally the uncomfortable reality, of a struggle for primacy between the president’s close aides and myself,” General Haig said later.

That narrative frustrated General Haig, but everything he did seemed to strengthen it. He tangled with Vice President George H.W. Bush over which of them should lead a committee on crisis management. Then, on March 30, 1981, John Hinckley Jr. nearly assassinated Reagan. General Haig quickly arrived in the White House Situation Room. Bush was flying back from Texas when Haig went to address reporters in the briefing room.

“As of now, I am in control here in the White House,” General Haig told the nervous country watching on television, “pending return of the vice president and in close touch with him.”

The sound bite symbolized to many a disconcerting hunger for power.

General Haig was the ultimate Cold Warrior, seeing virtually every regional conflict as enmeshed with the larger struggle against the Soviet Union. At the State Department, he elevated the importance of Central America — pushing to support anti-communists in El Salvador to send a message that the Soviets shouldn’t think about interfering in the Western Hemisphere.

Reagan himself grew tired of General Haig, who objected to sending a letter the president personally wrote for Soviet leader Leonid Brezhnev on the grounds that the State Department staff should draft it.

On June 24, 1982, General Haig visited Reagan in the Oval Office and handed the president a list of complaints about the “cacophony of voices” speaking about the administration’s foreign policy. Reagan called him back in the next day and astonished him with a note accepting his resignation.

“The president was accepting a letter of resignation that I had not submitted,” General Haig wrote in his 1984 book “Caveat: Realism, Reagan, and Foreign Policy.”

“Caveat” was a score-settling account aimed at his critics in the White House, which made headlines during Reagan’s 1984 campaign for reelection. General Haig, who had been so loyal to Nixon, decried the Reagan foreign policy apparatus as “a ghost ship.”

“You heard the creak of the rigging and the groan of the timbers and sometimes even glimpsed the crew on deck,” he wrote. “But which of the crew had the helm?”

In 1988, as Reagan’s second term came to an end, General Haig decided to run for president. He struggled to raise money and build support, deciding to pull out of the Iowa caucuses so he could focus his efforts on the New Hampshire primary. Never having won elected office, observers quickly realized he wasn’t cut out for retail campaigning. He scoffed when people didn’t seem to know who he was. Those who did questioned his ties to Nixon.

With polls warning of impending humiliation in New Hampshire, General Haig dropped out of the race on the Friday before the critical first primary. He spent much of his campaign attacking Bush, and he quit the race with a final flash of what some viewed as vindictiveness toward the vice president by endorsing Sen. Robert J. Dole (R-Kan.).

In interviews, General Haig brushed off all those who criticized his manner and at times his methods.

“If you’re a guy who just comes in and occupies a position and keeps his head down, of course, life can be rather pleasant,” he once told The Washington Post in an interview. “They come and go in all their adulations. But if you have a firm set of ideas, and you want to make a difference, you’ve got to be controversial.”

Alexander M. Haig Jr. Dies at 85; Was Forceful Aide to 2 Presidents

Alexander M. Haig Jr., the four-star general who served as a confrontational secretary of state under President Ronald Reagan and a commanding White House chief of staff as the Nixon administration crumbled, died Saturday at the Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, according to a hospital spokesman. He was 85.

Mr. Haig was a rare American breed: a political general. His bids for the presidency quickly came undone. But his ambition to be president was thinly veiled, and that was his undoing. He knew, Reagan’s aide Lyn Nofziger once said, that “the third paragraph of his obit” would detail his conduct in the hours after President Reagan was shot, on March 30, 1981.

That day, Secretary of State Haig wrongly declared himself the acting president. “The helm is right here,” he told members of the Reagan cabinet in the White House Situation Room, “and that means right in this chair for now, constitutionally, until the vice president gets here.” His words were taped by Richard V. Allen, then the national security adviser.

His colleagues knew better. “There were three others ahead of Mr. Haig in the constitutional succession,” Mr. Allen wrote in 2001. “But Mr. Haig’s demeanor signaled that he might be ready for a quarrel, and there was no point in provoking one.”

Mr. Haig then asked, “How do you get to the press room?” He raced upstairs and went directly to the lectern before a television audience of millions. His knuckles whitening, his arms shaking, Mr. Haig declared to the world, “I am in control here, in the White House.” He did not give that appearance.

Seven years before, Mr. Haig really had been in control. He was widely perceived as the acting president during the final months of the Nixon administration.

He kept the White House running as the distraught and despondent commander in chief was driven from power by the threat of impeachment in 1974. “He was the president toward the end,” William B. Saxbe, the United States attorney general in 1974, was quoted as saying in “Nixon: An Oral History of His Presidency” (HarperCollins, 1994). “He held that office together.”

Henry A. Kissinger, his mentor and master in the Nixon White House, also said the nation owed Mr. Haig its gratitude for steering the ship of state through dangerous waters in the final days of the Nixon era. “By sheer willpower, dedication and self-discipline, he held the government together,” Mr. Kissinger wrote in the memoir “Years of Upheaval.”

Mr. Haig took pride in his cool handling of a constitutional crisis without precedent.

“There were no tanks,” he said during a hearing on his nomination as secretary of state in 1981. “There were not any sandbags outside the White House.”

Serving the Nixon White House from 1969 to 1974, Mr. Haig went from colonel to four-star general without holding a major battlefield command, an extraordinary rise with few if any precedents in American military history.

But the White House was its own battlefield in those years. He won his stars through his tireless service to President Richard M. Nixon and Mr. Nixon’s national security adviser, Mr. Kissinger.

Mr. Haig never lost his will. But he frequently lost his composure as Mr. Reagan’s secretary of state. As a consequence, he lost both his job and his standing in the American government.

Mr. Nixon had privately suggested to the Reagan transition team that Mr. Haig would make a great secretary of state. Upon his appointment, Mr. Haig declared himself “the vicar of foreign policy” — in the Roman Catholic Church, to which he belonged, the pope is the “vicar of Christ” — but he soon became an apostate in the new administration.

He alienated his affable commander in chief and the vice president, George H. W. Bush, whose national security aide, Donald P. Gregg, described Mr. Haig as “a cobra among garter snakes.”

Mr. Haig served for 17 months before Mr. Reagan dismissed him with a one-page letter on June 24, 1982.

Those months were marked by a largely covert paramilitary campaign against Central American leftists, a heightening of nuclear tensions with the Soviet Union, and dismay among American allies about the lurching course of American foreign policy.

In the immediate aftermath of his departure came the deaths of 241 American Marines in a terrorist bombing in Beirut and, two days later, the American invasion of the Caribbean nation of Grenada.

“His tenure as secretary of state was very traumatic,” John M. Poindexter, later Mr. Reagan’s national security adviser, recalled in the oral history “Reagan: The Man and His Presidency” (Houghton Mifflin, 1998). “As a result of this constant tension that existed between the White House and the State Department about who was going to be responsible for national security and foreign policy, we got very little done.”

Mr. Haig said the president had assured him that he “would be the spokesman for the U.S. government.” But he came to believe — with reason — that the White House staff had banded together against him.

He blamed in particular the so-called troika of James A. Baker III, Edwin Meese III and Michael K. Deaver.

“Reagan was a cipher,” Mr. Haig said with evident bitterness. “These men were running the government.”

He reflected: “Having been a White House chief of staff, and having lived in the White House under great tension, you know that the White House attracts extremely ambitious people. Those who get to the top are usually prepared to go to extraordinary lengths to get there.”

Mr. Haig briefly considered running for president in 1980 and became a candidate in 1988, but his campaign attracted virtually no popular support.

A spokesman for Johns Hopkins, Gary Stephenson, said Mr. Haig’s death was caused by staphylococcal infection that he had before his admission to the hospital. Mr. Haig is survived by his wife, the former Patricia Fox, 81; their three children, Alexander Patrick Haig Sr. and Barbara Haig, both of Washington, and Brian Haig of Hopewell, N.J.; and eight grandchildren, according to the Rev. Frank Haig, 81, his brother and a professor emeritus of physics at Loyola University Maryland in Baltimore.

Father Haig said the Army was coordinating a Mass at Fort Myers in Washington and an interment at Arlington National Cemetery, but both would be delayed by about two weeks due to the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq.

In a statement issued Saturday, President Obama said: “Today we mourn the loss of Alexander Haig, a great American who served our country with distinction. General Haig exemplified our finest warrior-diplomat tradition of those who dedicate their lives to public service.”

Alexander Meigs Haig Jr. was born in Philadelphia on December 2, 1924, the son of a lawyer and a homemaker. At 22, he graduated from West Point, ranking 214th of 310 members of the class of 1947.

As a young lieutenant, he went to Japan to serve as an aide to Gen. Alonzo P. Fox, deputy chief of staff to Gen. Douglas MacArthur, the supreme allied commander and American viceroy of the Far East.

In 1950, Mr. Haig married the general’s daughter.

Mr. Haig’s first taste of war was brutal. In the first months of the Korean War, he served on the staff of Major General Edward M. Almond, chief of staff of the Far Eastern Command. Official Army histories depict General Almond as a terror to his underlings and as one of General MacArthur’s most uncompromising disciples.

Following orders, General Almond sent thousands of American soldiers north toward the Chinese border in November 1950. They met a ferocious surprise counterattack from a far larger Chinese force.

General Almond and Lieutenant Haig flew to the forward outpost of an American task force on November 28, where the general pinned a medal on a lieutenant colonel’s parka, told him the Chinese were only stragglers, and then flew off. Of that task force, once 2,500 strong, some 1,000 were killed, wounded, captured or left to die. In all, within two weeks, American forces in Korea took 12,975 casualties, in one of the worst routs in American military history.

After the Korean War, the young officer served at the Pentagon and eventually become a deputy special assistant to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. He served in Vietnam in 1966 and 1967 as a battalion and brigade commander of the First Infantry Division, and received the Distinguished Service Cross.

In 1969, Colonel Haig became a military assistant on the staff of Mr. Kissinger’s National Security Council. He distinguished himself as the hardest worker in an ambitious and talented cohort. Soon he was a brigadier general and Mr. Kissinger’s deputy.

Vietnam consumed General Haig. He made 14 trips to Southeast Asia from 1970 to 1973. He later said that Mr. Kissinger “got snookered” in negotiations with the enemy, and that he would have chosen to be more forceful. “That is how Eisenhower settled Korea,” Mr. Haig said. “He told them he was going to nuke them. In Vietnam, we didn’t have to use nuclear weapons; all we had to do was to act like a nation.”

Then Watergate consumed the White House. In 1973, after a brief stint as the Army’s vice chief of staff, General Haig was summoned back as chief of staff, replacing H. R. Haldeman, who later went to prison.

All this, in the course of a few weeks in the fall of 1973, fell on Mr. Haig’s head:

Vice President Spiro T. Agnew pleaded no contest to taking bribes. The next man in line under the Constitution, House Speaker Carl Albert, was being treated for alcoholism. The president himself, by some accounts, was drinking heavily. War broke out in the Middle East. When the president tried to fire the Watergate special prosecutor, Archibald Cox, rather than surrender his secret White House tapes, the attorney general, Elliot L. Richardson, and his deputy, William D. Ruckelshaus, resigned. Impeachment loomed.

What began with the arrest of several men breaking into Democratic headquarters at the Watergate complex in Washington in June 1972 had poisoned the presidency. Days after the break-in, the president and his closest aides had discussed how to cover up their role and how to obtain hush money for the burglars. The discussions, secretly taped by the president, were evidence of obstruction of justice.

General Haig was one of the first people, if not the very first person, to read transcripts of the tapes the president had withheld from the special prosecutor. “When I finished reading it,” he says in “Nixon: An Oral History,” “I knew that Nixon would never survive — no way.”

On Aug. 1, 1974, the general went to Vice President Gerald R. Ford and discussed the possibility of a pardon for the president. Mr. Nixon left office a week later; the pardon came the next month. Public outrage was deep. Mr. Haig soon departed.

After leaving the White House in October 1974, he became supreme allied commander in Europe, the overseer of NATO. In 1979, he resigned and retired from the Army. He served for a year as president of United Technologies.

A “Haig for President” committee was formed but dissolved in 1980. Mr. Haig made a full-fledged run for the Republican nomination in 1988. But he placed last among the six Republican candidates in Iowa, where he barely campaigned, and he withdrew before the New Hampshire primary. He had been, he said, “the darkest of the dark horses.”

In his 80s, Mr. Haig ran Worldwide Associates, a firm offering “strategic advice” on global commerce. He also appeared on Fox News as a military and political analyst.

He had a unique way with words. In a 1981 “On Language” column, William Safire of The New York Times, a veteran of the Nixon White House, called it “haigravation.”

Nouns became verbs or adverbs: “I’ll have to caveat my response, Senator.” (Caveat is Latin for “let him beware.” In English, it means “warning.” In Mr. Haig’s lexicon, it meant to say something with a warning that it might or might not be so.)

Haigspeak could be subtle: “There are nuance-al differences between Henry Kissinger and me on that.” It could be dramatic: “Some sinister force” had erased one of Mr. Nixon’s subpoenaed Watergate tapes, creating an 18 1/2- minute gap. Sometimes it was an emblem of the never-ending battle between politics and the English language: “careful caution,” “epistemologically-wise,” “saddle myself with a statistical fence.”

But he could also speak with clarity and conviction about the presidents he served, and about his own role in government. Mr. Nixon would always be remembered for Watergate, he said, “because the event had such major historic consequences for the country: a fundamental discrediting of respect for the office; a new skepticism about politics in general, which every American feels.”

Mr. Reagan, he said, would be remembered for having had “the good fortune of having been president when the Evil Empire began to unravel.” But, he went on, “to consider that standing tall in Grenada, or building Star Wars, brought the Russians to their knees is a distortion of historic reality. The internal contradictions of Marxism brought it to its knees.”

He was brutally candid about his own run for office and his subsequent distaste for political life. “Not being a politician, I think I can say this: The life of a politician in America is sleaze,” he told the authors of “Nixon: An Oral History.”

“I didn’t realize it until I started to run for office,” he said. “But there is hardly a straight guy in the business. As Nixon always said to me — and he took great pride in it — ‘Al, I never took a dollar. I had somebody else do it.’ ”

A funeral for General Alexander M. Haig’s will be held Tuesday, 2 March 2010, in Washington, D.C., his brother, Rev. Frank Haig, said.

Services will be at 10 a.m. at the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, 400 Michigan Ave. NE, Washington, D.C. Burial will follow at Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

A public viewing will be held from 2-9 p.m. Monday at Joseph Gawler’s Sons funeral home at 5131 Wisconsin Ave. NW in Washington.

No services are currently planned in Palm Beach, the Rev. Haig said.

General Haig, 85, died Saturday. He had been at Johns Hopkins Hospital for about three weeks before his death.

In addition to his brother, General Haig is survived by his wife, Patricia; a daughter, Barbara; two sons, Brian and Alexander; and eight grandchildren.

A military honor guard marches ahead of the Caisson team carrying the casket of former Secretary of

State, General Alexander Haig, during his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery Tuesday, March 2, 2010

A horse-drawn caisson carries the casket of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of

State Alexander M. Haig Jr to his burial site at his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

A horse-drawn caisson carries retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of State

Alexander M. Haig Jr to his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Patricia Haig (C), widow of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of State

Alexander Haig Jr., leads the the funeral procession of her husband at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010.

Patricia Haig, (2nd L) widow of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of State

Alexander M. Haig Jr, is escorted by Director of the Army Staff, Lieutenant General David Huntoon during Alexander Haig’s

funeral at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010.

A military honor guard carries a casket of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of

State Alexander M. Haig Jr during his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

A military honor guard carries the casket of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of

State Alexander M. Haig Jr during his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

A military honor guard places the casket of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of State

Alexander M. Haig Jr at his burial place during his funeral in Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Rev. Frank Haig (C) gives the benediction at the funeral of his brother, retired U.S. Army General

and former Secretary of State Alexander M. Haig Jr, at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Patricia Haig (seated 4th R), widow of retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary of State

Alexander M. Haig Jr, sits with family members at Haig’s funeral in Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Director of the Army Staff, Lieutenant General David Huntoon (L) presents the flag that draped the casket of retired U.S.

Army General and former Secretary of State Alexander Haig to his widow, Patricia Haig,

during his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Patricia Haig lays a rose on the casket of her husband, retired U.S. Army General and former Secretary

of State Alexander M. Haig Jr, during his funeral at Arlington National Cemetery March 2, 2010

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard