Born on February 15, 1935, Roger B., Chaffee graduated from Purdue University and served as a Naval test pilot before being selected for the Astronaut Program.

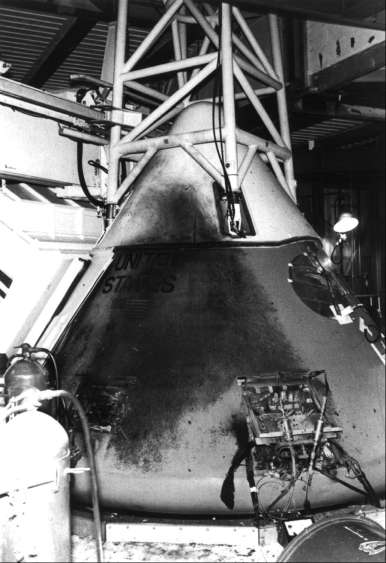

He was killed on January 27, 1967, along with Lieutenant Colonel Virgil I. Grissom, USAF, and Edward White, Lieutenant Colonel, USAF, when fire swept through the cockpit of Apollo 1 while they were completing tests prior to their scheduled flight on February 21, 1967. The flight was to have been the beginning of U.S. efforts to put a man on the moon.

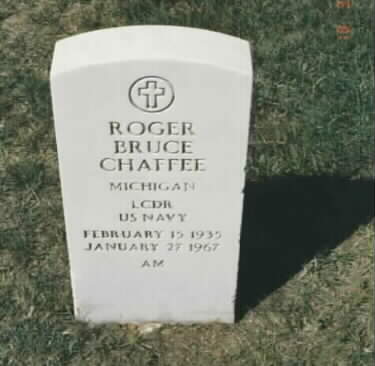

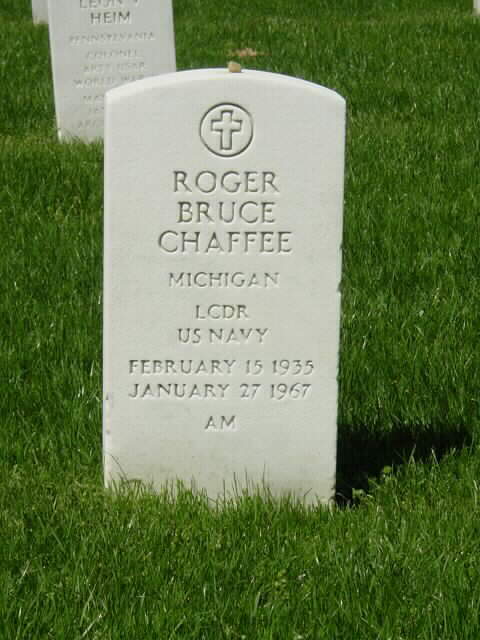

He is buried in Section 3 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the grave of Grissom and other Astronauts.

For Complete Information On The Accident, Click Here

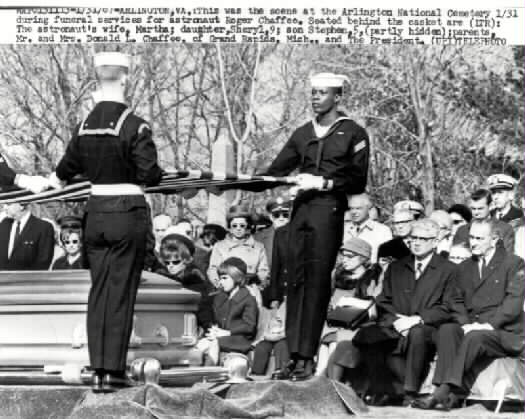

Funeral procession for Roger Bruce Chaffee

Commander Chaffee’s Son At The Funeral Service

President Lyndon B. Johnson With Commander Chaffee’s Father At The Funeral Service

Detailed Biography: Courtesy of NASA:

“You’ll be flying along some nights with a full moon. You’re up at 45,000 feet. Up there you can see it like you can’t see it down here. It’s just the big, bright, clear moon. You look up there and just say to yourself: I’ve got to get up there. I’ve just got to get one of those flights.”

-Roger Chaffee (The New York Times, January 29, 1967

“On my honor, I will do my best…” are the first eight words of the Scout Oath for the Boy Scouts of America. Individually, the words are short and simple. Collectively, however, they speak volumes and serve to inspire millions of boys to strive for excellence. Lieutenant Commander Roger Bruce Chaffee was a Scout for whom the Oath was more than just mere words. He took the pledge to heart and accepted the challenge to fully live the words of the Oath. Whether he was meticulously hand crafting items from wood or training to be the youngest man ever to fly in space, Chaffee always did his best by putting one hundred percent of himself into the effort.

In the early part of this century, various illnesses claimed many lives. One of the most dreaded of these diseases was scarlet fever. In January 1935, Don Chaffee came down with a case of scarlet fever and immediately was placed under quarantine. Because the disease was considered to be highly contagious and very serious, his wife, Blanche was told that she would not be allowed to deliver her baby at the local hospital; officials simply could not risk exposing other patients to the illness. Additionally, she could not give birth in their own home because of the risk of infection to both mother and newborn. Therefore, Blanche, nicknamed “Mike” and her two year old daughter, Donna moved in with her parents at their home in nearby Grand Rapids, Michigan. Roger Bruce Chaffee was born two weeks later on February 15, 1935. Toward the end of the month, Don Chaffee was removed from quarantine and brought his family back home to Greenville, Michigan, where they lived for the next seven years.

Earlier in his career, Don Chaffee had been a barnstorming pilot who flew a Waco 10 biplane. He was a regular site at fairgrounds and made a bit of extra money on the side by transporting passengers. He also piloted planes for parachute jumpers. Later, Don worked for Army Ordnance in Greenville and in 1942, he was transferred to the Doehler-Jarvis plant in Grand Rapids, Michigan where he served as Chief Inspector of Army Ordnance.

Don shared his love of flying with his son and at the age of seven, Roger enjoyed his first ride in an airplane when the family went on a short excursion over Lake Michigan. Although it was a relatively brief flight, Roger was absolutely thrilled. To satisfy his continued interested in planes, Don set up a card table in the living room where he and Roger would create model airplanes piece by piece. By the time he was nine, Roger would point to a plane flying overhead and predict, “I’ll be up there flying in one of those someday”.

Roger’s youth was characterized by strong family ties reinforced by activities involving his mother, father and sister. Trips to the Holland Tulip Festival delighted the entire family. The Ramona Amusement Park was a wonderful summertime attraction to which the family went on a weekly basis. The Chaffees also kept in close contact with grandparents and tried to make an annual trip to Canada to visit with extended family members. Ice skating, fishing, swimming, badminton and croquet were enjoyed as a family.

Chaffee established himself as a well-rounded individual at an early age. He loved making and flying model airplanes, but he also enjoyed his electric train set which snaked throughout the living room. He inherited a love and appreciation for guns from his grandfather, with whom he would spend hours target shooting at a nearby gravel pit or cleaning and polishing their firearms. Roger became interested in music in the fifth grade, participating in the city-wide chorus and playing the French horn in the school band. He later switched to the cornet and eventually progressed to the trumpet. Once he reached high school, he put his musical talent to work by forming a band with several other boys which hired itself out to play at post-game dances.

Although his parents provided him with a small allowance as compensation for chores done around the house, Roger always had a flair for finding ways to make a little extra money. He was on the road every morning by five o’clock delivering newspapers. Some of his elderly customers greatly valued his dependability and hired him to do odd jobs and run errands. Many homeowners in the area accepted the enterprising young lad’s offer to stencil their house numbers on the front step risers for the grand sum of one dollar per job.

At the age of thirteen, Chaffee branched out his interests once again by becoming a member of a local Boy Scout troop. He soon began earning merit badges. After the first year, he had acquired a total of ten badges and was awarded the Order of the Arrow. Numerous other merit badges followed and by the time Chaffee was a high school junior, he had earned most every possible badge. Roger achieved the rank of Eagle Scout and later was presented with the Bronze and Gold Palms which signified that he had earned additional badges after becoming an Eagle Scout. Throughout his years in scouting, Roger was an enthusiastic participant at summer camp, gaining many practical skills in camping, cooking and outdoor living. He served one year as Assistant Water-Front Director teaching inexperienced scouts how to swim. His scouting experience and business sense also proved useful in his after school job at the Boy Scout section of a local department store.

By the time Roger was fourteen, he had developed an interest in electronics engineering and tinkered with various radio projects in his spare time. In high school, he received excellent grades and maintained a 92 average. Vocational tests showed that Roger’s strongest abilities were in the area of science. He also scored high mechanically and artistically. Mathematics and science were his favorite subjects, with chemistry being particularly appealing. Once the family switched to a gas heating system, Roger transformed the outdated coal bin area into his own private workshop where he spent countless hours experimenting with his chemistry set. By the time he was a junior in high school, he was leaning toward a career as a nuclear physicist. As a senior, he established a lofty goal for himself: he wanted to someday have his name written in history books. Before the world’s super powers took their first halting steps into space, Roger Chaffee had shared his dream of being the first man on the moon with his closest friends.

On June 11, 1953, Roger Chaffee graduated in the top fifth of his class from Central High School in Grand Rapids, Michigan. He applied for scholarships from Annapolis, Rhodes and the Naval Reserve Officers Training Corps (NROTC). Because he was not yet ready to make the required permanent commitment to the U.S. Navy, he felt obliged to turn down his appointment to Annapolis. The Rhodes scholarship was not available to candidates who desired to major in engineering. NROTC offered Chaffee a Naval scholarship and in September 1953, he began the fall semester at the Illinois Institute of Technology in Chicago. After living in the campus men’s hall for three weeks, he moved into the Phi Kappa Sigma fraternity house. He made the Dean’s List and completed his freshman year with a B+ average. By the end of his first year at the Institute, Chaffee had decided to combine his love of flying with his aptitude in science and mathematics in order to pursue a degree in aeronautical engineering. Having made this decision, Roger applied to Purdue University in Lafayette, Indiana which was well-known for its quality aeronautical engineering program. His request to transfer from the Illinois Institute of Technology was approved by a review board in Washington, D.C. and Purdue accepted Chaffee as a transfer student for the 1954 fall semester.

In the summer of 1954, Chaffee was scheduled to report for duty onboard the battleship Wisconsin for an eight week voyage as part of the NROTC program. In order to qualify for the duty, he was required to take extra training and complete a variety of physical tests. He performed poorly during the eye examination. One eye was so weak that he nearly was failed on the spot. However, the attending physician gave him a break and told him that he would be allowed to retake the test the next morning. Passing the eye test was critical; if Chaffee did not pass the examination, he never would fly professionally. Roger spent part of the long night walking along the shores of Lake Michigan. Before dropping off to sleep, he offered numerous prayers for successful test results. The exam was repeated the next morning. Chaffee passed with flying colors and the attending physician certified him to participate in the NROTC program aboard the Wisconsin. During the two month cruise, Chaffee docked in far-off ports in England, Scotland, France and the island of Cuba.

Chaffee found himself with some extra time on his hands between the end of his eight week naval duty and the start of the new semester at Purdue. To fill the gap, his father found him a job operating a gear cutter. The gears were molded from soft black iron and “each day he came out at the end of his shift looking like a coal miner”. Although he appreciated earning the extra money, Roger, who liked things neat and clean, stated, “I learned one thing on this job. I’m not going to make my living this way for the rest of my life!”

In the fall of 1954, Chaffee arrived in Lafayette, Indiana and immediately sought out the Purdue chapter of his old fraternity. He lived at the frat house for the duration of his studies at the University. A job waiting on tables in one of the women’s residences provided him with an income, but Roger disliked working in such a prissy environment, where the character and decor definitely catered to more feminine tastes. He quickly found a different job by putting his mechanical and artistic skills to use as a draftsman for a small business near the campus. He remained with this position throughout his sophomore year. As a junior engineering student, Chaffee applied for a position in the Mathematics Department at Purdue and was hired to teach freshman math classes.

In September 1955, at the beginning of his junior year, Chaffee went on a blind date with a young woman from Oklahoma City named Martha Horn. His first impression of his date was that “she was a naive Southern girl”. Martha, a college freshman, considered Roger to be “a handsome but smart-alec upperclassman”. In spite of their first impressions of one another, they continued to date throughout the rest of the semester and by the end of the Christmas vacation, Martha had agreed to wear Roger’s fraternity pin. Chaffee introduced Martha to his parents in the fall of 1956 and confided to his father, “Dad, I’ve gone out with a lot of girls, but this is it. Someday I’ll marry Martha.” He followed through on his prediction and proposed to Martha Horn on October 12, 1956. The couple set a wedding date for the summer of 1957.

Chaffee’s second naval tour took place at the end of his junior year onboard the destroyer USS Perry. The points of destination for this cruise were the Scandinavian countries of Denmark and Sweden. He was unable to find temporary employment to finish out the summer break, so he began crafting a large model of a ship named The Cutty Sark to pass the time. He completed the project during spring break of his senior year. Recalling the many hours of work he had devoted to building the ship, Roger thought it was “too bad to have it sit around and gather dust”. He knew of a perfect spot for the ship back at Purdue. Having been elected as president of his fraternity, he had use of an office which was furnished with a large bookcase that seemed to be tailor made for housing The Cutty Sark. Therefore, he built a glass display case for his prized possession and brought it back

with him to Purdue.

During his final semester at the university, Chaffee began flight training as a NROTC air cadet flying a Cessna 172. He was judged to be ready to fly solo on March 29, 1957, only twenty four days after making his first flight out of the Purdue University Airport. After receiving additional dual and solo flight time, he took his private flight test on May 24, 1957 and passed with an above average grade of eighty six percent. David Kress, who administered the test, recommended Chaffee for further military flight training.

On June 2, 1957, Chaffee was awarded a BS in aeronautical engineering from Purdue University. He graduated with distinction and received a key to the National Society of Engineers as a result of his solid academic performance. Although his undergraduate days were over, Roger had every intention of continuing his education. “It took me four years to learn how little I knew. Knowledge is vast. There is so much more to learn, and I am going to take advantage of every opportunity that comes along.”

Chaffee completed his Naval training on August 22, 1957 and was commissioned as an Ensign in the U.S. Navy. Two days later, he traveled to Oklahoma City for his wedding to Martha Horn. After a fourteen day honeymoon trip to Colorado, Chaffee was assigned to temporary duties in Norfolk, Virginia. In November 1957, he reported for military flight training in Pensacola, Florida where he learned to fly the T-34 and T-28. He later was transferred to Kingsville, Texas to train on the F9F Cougar jet. He advanced quickly and was scheduled to begin advanced flight instruction in November 1958. One day before he left for his aircraft carrier training, he became the proud father of a healthy baby girl, Sheryl Lyn.

Although Roger did not like the thought of leaving his wife and newborn daughter, he realized that this particular training was critical to his career advancement. Accordingly, he reported for aircraft carrier training duty on November 18, 1958. Chaffee found landing an aircraft on a carrier to be a challenge, stating that “setting that big bird down on the flight deck was like landing on a postage stamp”. He compared night flight to “getting shot into a bottle of ink”. Chaffee completed his flight training and won his wings in early 1959.

Roger was given a variety of assignments and participated in numerous training duties over the next few years. He worked extensively on the A3D photo reconnaissance plane. Because of his complete understanding of the plane, he was granted permission to fly it, thus becoming one of the youngest pilots allowed to fly an A3D. While all of the additional experience and training proved to be very good for Chaffee’s naval career, it did require him to make sacrifices at home. Although he had managed to be present for the birth of his daughter, Chaffee was in Africa on a training mission when his son Stephen was born on July 3, 1961. He was able to spend a brief period of time with his family upon his return, but was soon shipped out to California to attend Safety and Reliability School. This particular training helped him in his duties as a safety and quality control officer at the Heavy Photographic Squadron 62 at the Jacksonville, Florida Naval Air Station. One of his primary duties was to create a quality control manual geared for maintaining flight squadron operations. His guidebook was extremely precise and some considered it to be overly exacting. However, others “respected his judgment… and knew that he had their welfare at heart”. They were right. Chaffee already had lost more than one of his Navy buddies in flying accidents and, as a result, he became very aware that “there’s only room for one mistake. You can buy the farm only once.” For Roger, “there was only one way… the perfect way; nothing less would do”. In spite of his drive for perfection, Squadron 62 overwhelmingly supported Chaffee, in part because he never asked the men to do anything that he wasn’t willing to do himself.

Another of Chaffee’s duties while serving with the V.A.P. 62 Squadron was to photograph Cape Canaveral, which was gearing up to become the launch area for the newly created manned space program. He also flew numerous flights to Cuba, often as many as three a day. During one such mission, he took important aerial photographs which gave crucial documentation of the Cuban missile buildup. When he was not flying for the Navy, he gave private flying instructions to civilians in exchange for his personal use of their plane. Additionally, he began taking graduate level courses in engineering. Chaffee ultimately knew the direction in which he wanted to head and he knew how to get there. “Ever since the first seven Mercury astronauts were named, I’ve been keeping my studies up… At the end of each year, the Navy asks its officers what type of duty they would aspire to. Each year, I indicated I wanted to train as a test pilot for astronaut status.” When NASA began recruiting for its third group of astronauts in mid 1962, Roger Chaffee became part of an initial pool of 1,800 applicants who sought one of the coveted positions opening up in the astronaut corps.

In late 1962, Roger was given the opportunity to pursue a Master’s degree in reliability engineering in earnest. He gladly accepted the invitation and moved his family to Dayton, Ohio in order to study at the Air Force Institute of Technology at Wright-Patterson AFB. While keeping up with his studies, Chaffee continued to participate in astronaut candidate testing. By mid June of 1963, the number of pilots competing for the spots had dropped to 271. Various physical and psychological tests were administered repeatedly. This time, Chaffee experienced no difficulties with the eye examinations. However, one of the physical tests did show that he had a very small lung capacity. As the weeks dragged by, psychologists continued to probe their minds by administering Rorschach ink blot tests and personality inventories. They rated their intellectual capacity with standard Intelligence Quotient tests. Physicians poked, prodded, x-rayed and tested each man and managed to violate virtually every part of their bodies from head to toe in the process. No anatomical part or function was left unchecked. Chaffee stated that “They managed to thoroughly humiliate us at least three times a day!” After what seemed to be an eternity, the candidates completed the grueling series of qualifying exams and returned home to wait anxiously for NASA to complete its selection process.

To ease the tension of waiting for a telephone call that might never come, Roger went on a brief hunting trip to Michigan. When he returned home on October 14, Chaffee learned that NASA had called while he had been away hunting. Upon contacting the headquarters in Houston, he was told that he had been selected as one of America’s newest astronauts. On October 18, 1963, Roger Chaffee flew to Houston and was officially named to the astronaut corps. He was joined by thirteen other pilots:

- Major Edwin E. Aldrin, Jr., U.S. Air Force

- Captain William A. Anders, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Charles A. Bassett II, U.S. Air Force

- Lieutenant Alan L. Bean, U.S. Navy

- Lieutenant Eugene A. Cernan, U.S. Navy

- Captain Michael Collins, U.S. Air Force

- Mr. R. Walter Cunningham

- Captain Donn F. Eisele, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Theodore C. Freeman, U.S. Air Force

- Lieutenant Commander Richard F. Gordon, U.S. Navy

- Mr. Russell L. Schweickart

- Captain David R. Scott, U.S. Air Force

- Captain Clifton C. Williams, U.S. Marine Corps

After spending the Christmas holidays with family in Michigan and Oklahoma, the Chaffees went about the business of moving to Houston, Texas, home of the new Manned Space Center. Having been transferred so many times before, moving was second nature to them by now. They found temporary living quarters in a duplex apartment in Clear Lake City. The family remained in the apartment for several months while Roger drafted plans for their new house and finalized arrangements on a building lot in Nassau Bay. Construction of their yellow brick home began in March and was completed shortly after. The house “seemed to signal his personality – well-planned, modern, independent – white rugs and a Grecian bathtub – a lush but spick-and-span formality”.

Although Chaffee always “wanted to fly and perform adventurous flying tasks”, he was realistic about his new role as an astronaut. “It won’t be just a throttle-jockey job; anyone can fly a plane, you know. It will be an engineering job, a tremendous scientific challenge.” (18) However, Chaffee and the other thirteen rookies soon discovered what sixteen other men had learned already: there was much more to being an astronaut than simply knowing how to fly and work a slide rule.

Training for the third crop of astronauts began in earnest in 1964. It was estimated that each astronaut would “spend fifty hours a week for two to five years training for a single flight”. The initial phase focused on academics. The instruction was intense, with various concepts and procedures from assorted professional fields crammed into countless hours of college-level lectures. Field trips supplemented the typical class work in order to gain hands-on experience. The Grand Canyon yielded information about earth’s geography. Kitt Peak National Observatory in Arizona offered opportunities to study lunar craters. New Mexico’s Slate Hill allowed the men to become familiar with the various surveying instruments and techniques which would be used to map and measure the moon. Rock formations and lava flows were studied in Alaska, Iceland and Hawaii.

Having stretched their intellects, the astronauts moved into the second phase of instruction, or contingency training. The purpose of the survival exercises was to prepare crews to handle unexpected emergencies, such as a land landing in remote areas or a crisis after splashdown. Chaffee’s introduction to the second phase of training took place in Panama where he and his colleagues were dropped into the middle of the jungle by helicopter and paired off to fend for themselves.

Thanks to his Boy Scout training, Roger had more outdoor living experience than some of the other men. Still, jungle survival was a challenge. Because the men carried only their parachutes and survival kits, they needed to make do with whatever indigenous food items they could scrounge up. Roger managed to find a variety of edibles during his three day trek. “He described the hearts of palm trees as delicious, snakes and iguana lizards as not so delicious and crabs and land snails as just plain terrible.”

Having managed to survive for three days in a jungle environment, Chaffee and his peers moved on to dealing with a different type of contingency plan: survival in desert terrain. To achieve the maximum effect, the training took place in the desert near Reno, Nevada during the month of August when ground temperatures soared to 160 degrees. Wearing only long underwear, shoes and loose-fitting robes which they had fashioned from parachutes, the astronauts paired off for two days in the scorching desert. Lizards and snakes provided most of their meals. Inflated life rafts served as mattresses and parachutes were rigged up as tents. Once Chaffee had settled into his new “home”, he commented, “We’re real cozy… Of course, it could use some wallpaper!”

The final phase of instruction was classified as operational training and focused on exposing astronauts to the various equipment and systems associated with the spacecraft and boosters as well as the physical sensations and experiences related to space flight. Accordingly, Chaffee and his colleagues spent hours perfecting their skills in spacecraft simulators and learning how to handle problems that might occur during an actual flight. They rehearsed water egress procedures and rescue techniques. Their bodies were prepared to withstand the high G forces they would encounter during launch and reentry. Flights on board Air Force cargo planes allowed them to experience brief periods of weightlessness. Techniques and movements used in Extravehicular Activity (EVA) were refined during underwater training. They visited manufacturing plants to keep an eye on spacecraft production.

One of Chaffee’s most valuable training experiences came in the form of serving as one of the capsule communicators (capcom) for the Gemini 4 mission in June 1965. He relayed information back and forth between crew members Jim McDivitt and Ed White and the Director of Flight Crew Operations, Christopher Kraft. Chaffee served in this capacity along with Eugene Cernan and chief capcom, Gus Grissom at the recently completed Manned Space Center in Houston. He also was paired up with Grissom to fly chase planes up to a level of fifty thousand feet in order to take pictures of the launch of an unmanned Saturn 1B rocket.

On October 31, 1964, the law of averages had reared its ugly head and the astronaut corps lost its first member when Ted Freeman died in a jet crash during a routine training mission. Fate was kind for nearly two more years. Then, Charlie Bassett and Elliott See were lost when they clipped off part of the McDonnell plant building during an attempted landing in St. Louis. Although the overall death toll stood at three, no lives had been lost in accidents directly related to space flight. Chaffee served as pallbearer for Elliott See, accompanying his body as it was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. Once the proper condolences had been paid, however, it was back to business as usual and the men resumed their training.

Over the years, Chaffee had developed a variety of ways to deal with all of the stress produced by the intensity and serious nature of his work. Hunting, his gun collection and home improvement projects filled his need for relaxation. He tackled each of these pastimes with the same passion he brought to his job. Roger used his woodworking skills to build a magnificent gun cabinet to house his growing collection of firearms. His first 22 rifle, which had been a gift from his parents on his twelfth birthday, a 300 Weatherby, and two old guns which Chaffee had rebuilt, reconditioned and refinished graced the cabinet. “He took great pride in making his own rifles, ordering some of the barrels and lock works from Belgium and carving the stocks from wood which he had brought back from his trip to Hawaii.” In addition, Chaffee never wasted his spent ammo shells. He owned all of the supplies and equipment, including scales, scoops, crimping machine, powder and ball necessary to reload his used casings.

Chaffee’s artistic streak was evident in the way he maintained his lawn and arranged the various trees, shrubs and flowers which dotted their property with the skill and eye of a professional landscaper. When Martha asked her husband to build a tiny water fountain in the backyard, she wound up with a carefully engineered waterfall crafted from tons of gravel and hours of backbreaking work. The cascading waterfall was complimented by the lighting Roger had installed around their pool. Additionally, he wired their stereo system so that music could be heard in any room of the house.

Less than one week after Neil Armstrong and David Scott completed their Gemini VIII flight, NASA named the astronauts who would fly the first Apollo Earth-orbit mission. Competition for the three positions had been intense with each man wanting a spot so badly he could taste it. Chaffee was no exception. He had been training specifically for space flight for nearly two and one half years and had yet to be named to a mission. He wanted his first flight to coincide with the first flight of the Apollo-Saturn spacecraft. When the preliminary announcement came on March 21, 1966, Chaffee discovered that he would be getting that for which he had been hoping. NASA had named Gus Grissom as Commander and Ed White as Senior Pilot. Chaffee would complete the crew as Pilot. James McDivitt, David Scott and Russell Schweickart were assigned as members of the back-up crew. Roger enthusiastically summed up his feelings about his role as Apollo I Pilot: “I’m extremely pleased to be named. I think it will be a lot of fun.” Chaffee beamed with pride when Grissom made his first public statement as Apollo I Commander: “I think we have a good crew and I think it will be a good flight.” When “asked if there was anything scary about a first space flight, [Chaffee] replied that there were a lot of unknowns and problems. This is our business… to find out if this thing will work for us. I don’t see how you could help but be a little bit excited. I don’t like to use the word scary.”

The primary purpose of the open-ended flight, which could last up to two weeks, was to test and evaluate all major spacecraft systems as well as the ground tracking and control facilities. The prime and back-up crews threw themselves into the intensive training schedule. Three days after the crew was first announced, Chaffee flew out to the North American Aviation Plant in Downey, California to check out production of the Apollo spacecraft. Chaffee had witnessed the manufacture and assembly of Gemini spacecraft. However, this was an entirely different situation. “We’re not talking generalities any more… That’s my spacecraft.” Over the next several months, Chaffee and the crew would come to know every square inch of AS 012. “We know it. We know that spacecraft as well as we know our own homes, you might say. Boy, we know every little rivet and wire and electrical terminal in it practically and all its idiosyncrasies.”

During the months of training, the crew members worked closely together, gaining insight into individual strengths, habits and personalities in the process. Chaffee established himself as “a tireless and meticulous workhorse, the self-appointed secretary for the trip who answered the endless questions when Gus and Ed got fed up, a constant tease to them – quick with the barb, with the quiet, off-hand comeback”. In addition, Roger proved himself to be extremely capable and knowledgeable in his field. Gus Grissom soon recognized and came to admire his Pilot’s engineering skills: “Roger is one of the smartest boys I’ve ever run into. He’s just a damn good engineer. There’s no other way to explain it. When he starts talking to engineers about their systems, he can just tear those damn guys apart. I’ve never seen one like him. He’s really a great boy.” In turn, Chaffee greatly admired both Grissom and White for their own accomplishments and abilities. However, he developed a special closeness with Gus. Chaffee soon adopted a variety of mannerisms and body language that were uniquely Grissom’s. He began to pepper his speech with several of the colorful words and phrases that Gus often used. Other Astronauts noticed Chaffee’s mimicry and teased him relentlessly about it. Yet, although he admired the veteran members of the crew, Chaffee never doubted his own abilities. When “asked if he felt secure under the wings of two experienced spacemen, he declared frankly: Oh, yes! But I don’t think it’s because they’ve flown and I haven’t. Hell, I’d feel secure taking it up all by myself because we’ve trained enough for every job. You feel secure because you know what you’re doing.”

As 1966 came to a close, the crew took some time to enjoy their families during the Christmas holiday. Each year, the Nassau Bay Garden Club sponsored a Christmas contest and awarded first place to the most beautifully decorated home. Roger enthusiastically entered the contest and devoted many hours to hanging strings of colorful lights in just the right place. The piece de resistance was the roof display which featured Santa and his reindeer. To enhance the effect, Roger used a series of carefully timed flashing lights which gave the illusion of the sleigh being pulled by the reindeer. He won first place.

Christmas 1966 also gave Roger the opportunity to present his wife with a very special gift. The crew members had designed a pin for each of their wives which they had planned to take with them during the flight of Apollo I. In their excitement over the upcoming mission, they caved in and gave the pins as Christmas gifts instead. “Since they had spoiled their own surprise, immediately after Christmas they had gold charms designed that they secretly planned to take with them into space and then present to their wives. Each unique little charm was an exact duplicate of the Apollo I Command and Service Modules with a little diamond representing the astronaut’s position in the craft.”

January 1967 found the crew involved nearly full time with the final round of pre-flight testing. In spite of his past technical and flying experience, Roger still was tagged as the rookie because he had no space flights to his credit. His solid accomplishments seemed to pale when placed next to Grissom’s and White’s. His boyish looks and young age were also obstacles. When asked to assess Chaffee as a future spaceman, Gus Grissom, who greatly valued Roger’s expertise, could only offer an educated guess regarding Chaffee’s upcoming performance: “Of course, Roger hasn’t had any experience [space] flying and we don’t know what he’ll be like. I’m sure he’ll be okay.” Apollo I would not be merely Chaffee’s ticket to getting his name in the history books. Apollo I would allow him, for the first time, to prove himself worthy of the title of “Astronaut” that had been bestowed upon him.

As the crew entered the Command Module for the plugs-out test on January 27, 1967, Chaffee took the Pilot’s couch on the right side of the spacecraft. His primary duty was to maintain communications with the Blockhouse as the test proceeded. The test was an extensive one that would drag on for hours so that the spacecraft could be evaluated, system by system and procedure by procedure. The job was a tough one that included numerous tedious, exacting, and frustrating tasks. Yet Chaffee’s personal philosophy and professional training had prepared him for exactly this sort of job.

“Probably the greatest thing a man can say to himself, or have as his philosophy when he has to tackle a tough job, or make a big decision, is the first eight words of the Scout Oath: On my honor, I will do my best…”

As the count continued and the test proceeded, Chaffee paid close attention to the spacecraft’s performance and maintained communications with those following the test from outside the Command Module. He saw nothing on his monitors to warn him that the plugs out test soon would become a harrowing nightmare during which his own philosophy would be put to the ultimate test. Before the evening came to a close, Roger Chaffee would prove himself most worthy of the title of “Astronaut”, not by flying in space, but by choosing to remain strapped into his couch, attempting to transmit emergency messages to the Blockhouse while fire raged mercilessly throughout the Apollo I spacecraft.

CHAFFEE, ROGER BRUCE

LT CMDR USN

- DATE OF BIRTH: 02/15/1935

- DATE OF DEATH: 01/27/1967

- BURIED AT: SECTION 3 SITE 2502-F

- ARLINGTON NATIONAL CEMETERY

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard