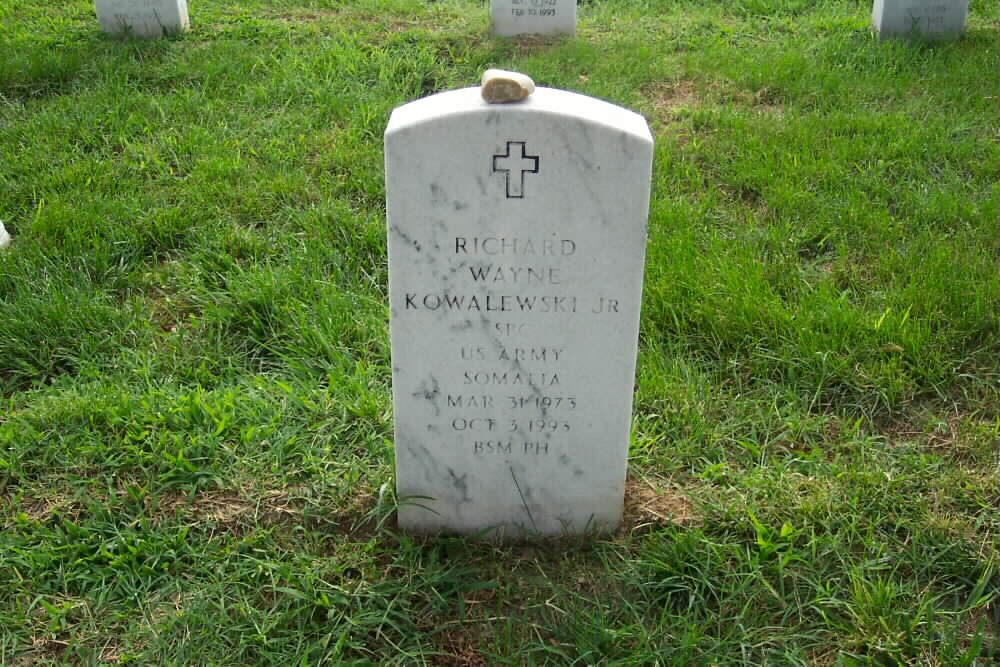

Richard W. Kowalewski, Jr.

Company B, 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment

Hello, I have noticed that Richard’s name was not listed under the Army Personnel Buried in Arlington.

He was killed on Oct 3, 1993, one of the Rangers killed in Somalia. He was laid to rest October 15, 1993 in section 60, grave 5789.

I was his fiancee. If you would like any information, please feel free to e-mail me.

Thank you,

Donna Yarish-Calvert

AN AMERICAN HERO

BY JON STEVENS

THE OBSERVER-REPORTER

Richard Kowalewski was not the typical “gung-ho” recruit when he joined the U.S. Army June 1, 1992, two days after graduating from Carmichaels Area High School.

He played chess, spoke German and loved the arts. He also loved Donna Yarish.

The two became high school sweethearts when Kowalewski returned to Greene County for his junior year. He was born in Waynesburg and lived in Crucible until he was 4 or 5 years old, when he moved with his family to Ohio. He then moved to Texas to live with his mother before returning to Crucible to live with his grandparents.

He was voted “most mannerly” of his senior class. He read literature, especially Shakespeare, and loved acting in school plays. But perhaps most of all, Kowalewski loved his country.

Kowalewski was 20 when he was killed October 3, 1993, during a search-and-rescue mission that went terribly wrong in Mogadishu, Somalia. He was a member of Weapons Platoon, Bravo Company, 3rd Ranger Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment, and was one of the 18 Ranger and Delta Force members who were killed in what has been described as the U.S. military’s single most costly firefight since Vietnam.

This story of a group of elite troops sent to Mogadishu as part of a United Nations peacekeeping mission – an attempt to abduct two top lieutenants of the Somali warlord Mohamed Farrah Aidid – and the subsequent tragic events of October 3 and 4 in which 18 soldiers died and 73 were wounded, became a best-selling book by Philadelphia Inquirer reporter Mark Bowden.

The story has now been transformed into a movie, “Black Hawk Down,” scheduled for national release Friday. Actor Brendan Sexton III plays the role of Kowalewski, who was called “Alphabet” by his buddies because his last name was hard to pronounce.

Yarish, now Donna Calvert, lives in Virginia with her husband. “I still have such fond memories of him,” Calvert said. “He wanted to attend the University of Pittsburgh and obtain a degree in architectural engineering,” she said.

Calvert said Kowalewski died doing something he believed in, “doing something great for all Americans.”

“While the movie will give a glimpse of the heroics of the Rangers, nothing will ever show how special these heroes truly were, or what they went through those terrible two days. We owe them all our heartfelt thanks and utmost respect,” she said.

The last time she saw him was July 4, 1993, at Fort Bliss, Texas. But on August 11, she received this letter:

“I love my country and everything it stands for. I am in a position that I may have to give my life for my country. That position is no different than every other American that has been called upon to put his or her life on the line for what they believe in. This country is the greatest nation on Earth, and I love it.

“I must also say a few words for the 3rd Ranger Battalion. As you know I love this, too. Despite how we fight and mess with each other, there is a bond here that you have to be a part of to understand. I am very confident in the leadership of the 3rd Batt. We are the best. From the RCO down, we are the best-trained officers and NCOs in the Army, hell the whole damn world for that fact. I will follow them anywhere and do anything they ask of me.”

Calvert receive a phone call from him August 24. “I knew he was leaving for somewhere, but I didn’t know where and he wouldn’t tell. The only clue I got was when he said, ‘Watch CNN very close.'”

Calvert continued to receive letters from him every day.

August 20:

“I kept waking up all night long. I sleep in the corner of our tent. I must have rolled over and stared at the stars for hours. There are a few times in a person’s life that really makes them think. One of those being when you think it may be your time to go.”

The on September 26, seven days before he would be killed, he wrote:

“Yesterday was probably the coldest, darkest, saddest day of my life. I stood at attention, rendering a salute as three American soldiers were rolled by in humvees, in caskets draped with American flags. These three men being the ones killed in action on Friday night. I stood by and watched as tears began to form in my eyes and the eyes of my fellow Rangers. We all felt a warm spot in our hearts for those brave men who gave their lives for God, country and his fellow American brothers and sisters, believing what they were doing was right. Not only does my heart go to these men, who made the greatest sacrifice of all, but their wives, children and loved ones. I feel for them the most. War is very sad and kills everyone in some way. I can’t help to think if it had been me in one of these caskets.”

The mission began at 2:49 p.m. Oct. 3 when the two principal targets were spotted at a building in Mogadishu. At 3:32 p.m., the force launched 19 aircraft, 12 vehicles and 150 men. At 3:42 p.m. a Ranger, Pvt. Todd Blackburn, fell from a helicopter 60 feet to the ground. Somali militia converged and there was chaos.

At 4:20 p.m. a Blackhawk helicopter was hit by a rocket-propelled grenade and crashed five blocks northeast of the target building. Twenty minutes later a second Blackhawk was hit and crashed. Kowalewski was part of a convoy sent to rescue downed pilots. But they became the “Lost Convoy,” wandering into one ambush after another, the men fighting to stay alive and find their way back to base.

Within minutes, Kowalewski would be killed.

In his last letter to Calvert, he perhaps sensed the final outcome. On the morning of October 3, he wrote:

“Somalia has forced me to wake up and take a hard look at my life. It has made me change a lot of my views. Most of all I’ve learned that there is no better time to say what you are thinking than right now. Because you may never get a chance to say it.”

Calvert said she is glad there is a movie “to remember great guys who were very courageous to do what they did.”

Calvert said she is not sure if she will see the movie because she said Kowalewski’s death was horrible.

According to the Bowden book, Kowalewski was driving a Humvee when he was shot in the shoulder. He absorbed the blow and kept on steering.

“Alphabet, want me to drive?” asked Pfc. Clay Othic, who was seated in the front seat.

“No, I’m OK.”

Bowden writes, “Othic was struggling in the confined space to apply pressure dressing to Alphabet’s bleeding shoulder when a grenade launcher rocketed in from the left. It severed Alphabet’s left arm and ripped into his torso. It didn’t explode. Instead, the two-foot-long missile was embedded in Alphabet’s chest, the fins protruding from his left side under his missing arm, the point sticking out the right side. He was killed instantly.”

“I don’t know if I can watch that,” Calvert said. “I want to remember him the way he was, but I would really like to see what he saw. I can’t even imagine.”

Footnote: On November 2, 2001, the United States froze the assets of 62 organizations and individuals suspected of raising money and providing other critical support for Osama bin Laden’s al-Qaida. One of them is al-Barakaat,

a conglomerate operating cell phone companies and postal services that has a significant presence in the United States and 40 other nations accused of funneling millions to bin Laden and his organization.

The base of operations for al-Barakaat is Mogadishu.

Private First Class Richard Kowaleski, Ranger, killed in the ground convoy

Photo Courtesy of the United States Army

PFC Richard Kowalewski, a 20-year-old Ranger who grew up in Texas, Alabama and Pennsylvania. His buddies called him Alphabet because his last name was hard to pronounce. He was driver of a five-ton truck in the main ground convoy.

Courtesy of the Philadelphia Inquirer:

SOME OF THE VEHICLES were almost out of ammunition. They had expended thousands of rounds. One of the 24 Somalian prisoners had been shot dead and another was wounded. The back ends of the remaining trucks and humvees in the lost convoy were slick with blood. Chunks of viscera clung to floors and inner walls.

The second humvee in line was dragging an axle and was being pushed by the five-ton truck behind it. Another humvee had three flat tires and two dozen bullet holes. SEAL Sgt. Howard Wasdin, who had been shot in both legs, had them draped up over the dash and stretched out on the hood. Yet another humvee had a grenade hole in the side and four flat tires.

They were shooting at everything now. They had abandoned their new mission – to rescue downed pilot Cliff Wolcott and then try to reach pilot Mike Durant’s crash site. Now they were fighting just to stay alive as the convoy wandered into one ambush after another, trying to find its way back to base.

Up in a humvee turret and behind a Mark 19, a machine gun grenade launcher, Spec. James Cavaco was pumping one big round after another into the windows of a building from which they were taking fire. It was hard to shoot the Mark 19 accurately, but Cavaco was dropping grenades neatly into the second-story windows one after another. Bang! Bang! Bang! Bang!

From his seat in the second five-ton, Spec. Eric Spalding shouted out to his friend: “Yeah! Get ’em, ‘Vaco!”

It was just after that when Cavaco, firing to his left down an alleyway, slumped forward. He had taken a round to the back of his head and was dead. Spalding helped load him on the back of the truck. They tossed his body up and it landed on the legs of an injured Ranger in back, who let out a shriek.

Sgt. Paul Leonard, one of the Delta soldiers, stepped up behind Cavaco’s Mark 19. He was even more of an expert shot. The big 40mm rounds were designed to penetrate two inches of steel before exploding. As Leonard fired, the rounds screamed right through the bodies of Somalian gunmen and exploded farther down the street.

But not long after he took over the gun, a bullet came through the side window of the humvee and took off the back of Leonard’s left leg just below the knee. He was standing in the turret, so all the men in the humvee were splattered with tissue and blood. The muscles of his leg hung open in oozing flaps. But Leonard was still standing, and still shooting. A Ranger tied a tourniquet around his leg.

The convoy was taking a beating, but it was also leaving a terrible swath of dead and wounded Somalis in its wake.

In another humvee, PFC Tory Carlson was shooting out the back, his .50-cal machine gun rocking the vehicle, when he saw three Somalian men cross the big gun’s range. Their bodies went flying, and as the rounds kept coming the bodies skipped and bounced along the ground until they were thrown against a wall. Then the men came apart.

Carlson was watching with horror and satisfaction when he felt a sudden blow and sharp pain in his right knee. It felt as if someone had taken a knife and held it to his knee and then driven it in with a sledgehammer. Carlson glanced down and saw blood rapidly staining his pants. He said a prayer and kept shooting. He had been wildly scared for longer now than he had ever been in his life, and now it was somehow worse. His heart banged in his chest and he found it hard to breathe and he thought he might die right then of fright.

His head was filled with the sounds of shooting and explosions and the visions of his friends going down, one by one. Blood splashed everywhere, oily and sticky with its dank, coppery smell. He figured, This is it for me. And then, in that moment of maximum terror, he felt it all abruptly, inexplicably fall away. He had stopped caring about himself. He would think about this a lot later, and his best explanation was that he no longer mattered, even to himself. He had passed through some sort of barrier. He had to keep fighting, because the other guys, his buddies, were all that mattered.

Spalding was sitting next to the passenger door in his truck with his rifle out the window, turned in the seat so he could line up his shots, when he was startled by a sudden flash of light down by his legs. It looked as if a laser beam had shot through the door and up into his right leg. Actually, a bullet had pierced the steel of the door and the window, which was rolled down, and had poked itself and fragments of glass and steel straight up his leg from just above his knee to his hip. He let out a squeal.

“What’s wrong, you hit?” shouted the truck’s driver, PVT John Maddox.

“Yes!”

And then another laser poked through, this one into Spalding’s left leg. He felt a jolt this time but no pain. He reached down to grab his right thigh, and blood spurted out between his fingers. Still Spalding felt no pain. He didn’t want to look at it.

Then Maddox began shouting, “I can’t see! I can’t see!”

Spalding turned to see Maddox’s helmet askew and his glasses knocked sideways on his head.

“Put your glasses on, you dumb ass.”

But Maddox had been hit in the back of the head. The round must have hit his helmet, which saved his life, but hit with such force that it had rendered him temporarily blind. The truck was rolling out of control, and Spalding, with both legs shot, couldn’t move over to grab the wheel.

They couldn’t stop right in the field of fire, so there was nothing to do but shout directions to Maddox, who still had his hands on the wheel.

“Turn left! Turn left! Now! Now!”

“Speed up”

“Slow down!”

The truck was weaving and banging into the sides of buildings. It ran over a Somalian man on crutches.

“What was that?” asked Maddox.

“Don’t worry about it. We just ran over somebody.”

And they laughed. They felt no pity and were beyond fear. They were both laughing as Maddox stopped the truck.

One of the Delta men, Sgt. Mike Foreman, ran up and opened the driver’s side door to find the cab splattered with Spalding’s blood.

“Holy s-!” he said.

Maddox slid over next to Spalding, who was examining his wounds. There was a perfectly round hole in his left knee, but no exit wound. The bullet had fragmented on impact with the door and glass, and only the metal jacket had penetrated his knee. It had flattened on impact with his kneecap and just slid around under the skin to the side of the joint. The rest of the bullet had peppered his lower leg, which was bleeding. Spalding propped both legs up on the dash and pressed a field dressing on one. He lay his rifle on the rim of the side window and changed the magazine. As Foreman got the truck moving again, Spalding resumed firing. He was shooting at anything that moved.

Spalding’s buddy, PFC Clay Othic, was wedged between driver and passenger in the truck behind them when PFC Richard Kowalewski, who was driving, was hit in the shoulder. He absorbed the blow and kept on steering.

“Alphabet, want me to drive?” asked Othic. Kowalewski was nicknamed “Alphabet,” for his long surname.

“No, I’m OK.”

Othic was struggling in the confined space to apply a pressure dressing to Alphabet’s bleeding shoulder when a grenade rocketed in from the left. It severed Alphabet’s left arm and ripped into his torso. It didn’t explode. Instead the two-foot-long missile was embedded in Alphabet’s chest, the fins protruding from his left side under his missing arm, the point sticking out the right side. He was killed instantly.

The driverless truck crashed into the rear of the truck ahead, the one with the prisoners in back and with Foreman, Maddox and Spalding in the cab. The impact threw Spalding against the side door, and his truck rolled off and veered into a wall.

Othic, who had been sitting between Alphabet and Spec. Aaron Hand when the grenade hit, was knocked unconscious. He snapped back awake when Hand shook him, yelling that he had to get out.

“It’s on fire!” Hand shouted.

The cab was black with smoke, and Othic could see a fuse glowing from what looked like the inside of Alphabet’s body. The grenade lodged in his chest was unexploded, but something had caused a blast. It might have been a flash bang grenade – a harmless grenade that gives off smoke and makes noise – mounted on Alphabet’s armor. Hand got his side door open and swung himself out. Othic reached over to grab Alphabet and pull him out, but the driver’s bloody clothes just lifted off his pierced torso.

Othic stumbled out to the street and realized that his and Hand’s helmets had been blown off. Hand’s rifle had been shattered. They moved numbly and even a little giddily. Alphabet was dead and their helmets had been knocked off, yet they were virtually unscathed by the grenade. Hand couldn’t hear out of his left ear, but that was it.

Hand found the lower portion of Alphabet’s arm on the street. All that remained intact was the hand. He picked it up and put it in his side pants pocket. He didn’t know what else to do, and it didn’t feel right leaving it behind. Dale Sizemore had to identify Richard Kowalewski’s body.

OTHIC CLIMBED INTO another humvee. As they set off again, he began groping on the floor with his good left hand, collecting rounds that guys had ejected from their weapons when they’d jammed. Then he passed them back to those still shooting.

They found a four-lane road with a median up the center that would lead them back down to the K-4 traffic circle, a major traffic roundabout in southern Mogadishu, and then home. In the truck, Spalding began to lose feeling in his fingertips. For the first ime in the ordeal he began to panic. He felt himself going into shock. He saw a little

Somalian boy cradling an AK-47, shooting it wildly from the hip. He saw flashes from the muzzle of the gun. Somebody shot the boy. Spalding felt as if everything around him had slowed down to half speed. He saw the boy’s legs fly up, as if he had slipped on marbles, and then he was flat on his back.

Foreman, the Delta sergeant, was a hell of a shot. He had his weapon in one hand and the steering wheel in the other. Spalding saw him gun down three Somalian men without even slowing down.

Spalding felt his fingers curling and his hands stiffening. His forearm had been shattered by a bullet earlier.

“Hey, man, let’s get the hell back,” Spalding said. “I’m not doing too good.”

“You’re doing cool,” Foreman said. “You’ll be all right. Hang in there.”

A humvee driven by SEAL Homer Nearpass was now in the lead. It was shot up and smoking, running on three rims. One dead and eight wounded Rangers were in the back. Wasdin, the wounded SEAL sergeant, had his bloody legs splayed out on the hood (he’d been shot once more, in the left foot).

They came upon a big roadblock. The Somalis had stretched two huge underground gasoline tanks across the roadway along with other debris, and had set it all on fire. Afraid to stop the humvee for fear it would not start up again, Nearpass shouted to the driver to just ram through it.

They crashed over and through the flaming debris, nearly landing on their side, but the sturdy humvee righted itself and kept on going. The rest of the column followed.

Staff Sgt. Matt Eversmann, the leader of a Ranger unit that had been rescued by the convoy, was curled up on one of the back passenger seats of his humvee, training his weapon out the window. At every intersection he saw Somalis who would open fire on any vehicle that came across. Because they had men on both sides of the street, any rounds that missed the vehicles as they flashed past would certainly have hit the Somalis on the other side of the road. What tactics, Eversmann thought. He felt these people must have no regard for even their own lives. They just did not care.

In his vehicle, Othic was on all fours now, groping around on the floor of the humvee with his good hand, looking for unspent shells. They were just about out of ammo.

As they approached K-4 circle, they all braced themselves for another vicious ambush.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard