Honor guard members lead the way as pallbearers from the Army’s 10th Mountain Division carry Shawn Mayerscik’s casket into St. Stephen Church on Thursday morning before funeral services. Mayerscik was among 11 soldiers killed when a Black Hawk helicopter crashed during a training exercise near Fort Drum, New York.

One day after coalition forces launched a war with Iraq, Oil City bid farewell to one of its own servicemen – a young man who was eager to see action in the Middle East.

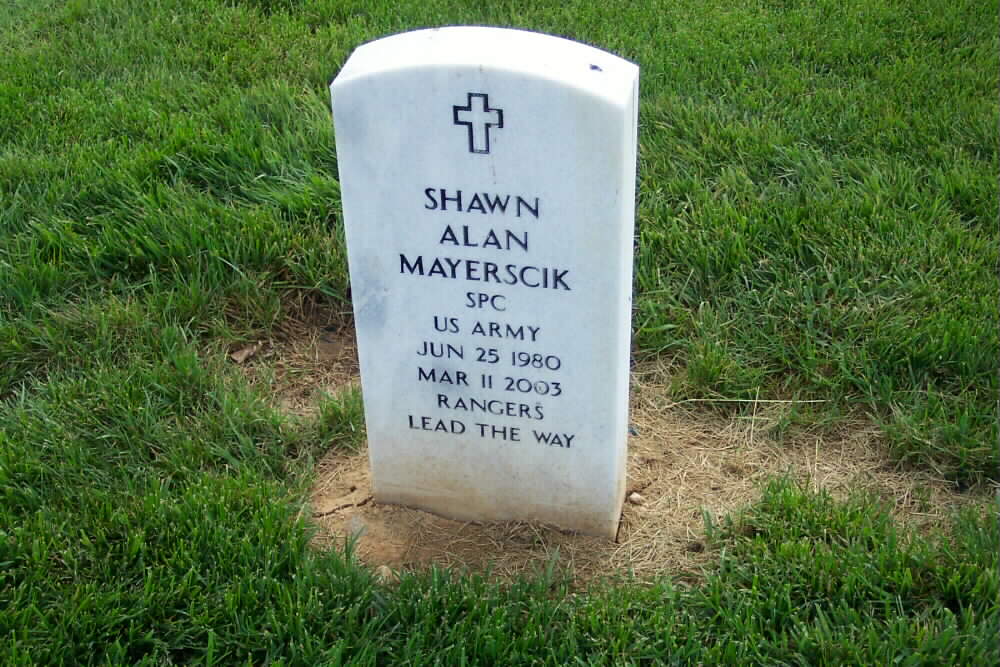

Shawn Alan Mayerscik, 22, of 17 Oakwood Drive and 10 others were killed in a Black Hawk helicopter crash March 11, 2003, in a wooded area outside Fort Drum, N.Y. The Army soldiers had completed an assault exercise and were returning to their airfield when the crash occurred.

“Shawn didn’t lose his life just training,” Army Captain Scott Austin told the congregation at a funeral mass Thursday. “He lost his life (training to defend our country).”

Austin was one of several enlisted Army men who paid tribute to their fallen comrade. The beret-wearing and green-suited men served as pallbearers and also fired a 21-gun salute from the front steps of St. Stephen Church at State and East First streets.

An emotional Austin, frequently stopping mid-sentence, spoke warmly of the humble friend he was proud to serve beside. He stood just feet from Mayerscik’s flag-draped, gray casket in the church, behind which was a shadow box display of the Oil City High School graduate’s military awards and service patches. The Army specialist had the awards mounted as a birthday gift for his mother, Kathy, in January.

Also on display was Mayerscik’s latest commendation, the Meritorious Service Award, which he posthumously received March 12.

The small medals and badges in the box flanked one large patch in the center of the display. It read “Operation Enduring Freedom.” Mayerscik served with U.S. forces in Afghanistan shortly after President Bush declared war on terrorism in September 2001.

“He fought for glory and honor,” Austin said.

“This young man was in Afghanistan saving the lost, picking them up and bringing them home,” said the Rev. Jeffrey Noble.

Austin said Mayerscik was psyched about moving onward to what he called the “big show” in Iraq. That goal was stopped short March 11.

“On March 11, 2003, a Black Hawk went down but rising from that accident was a nation freer and stronger. A Black Hawk went down, but rising from that accident was a family and community proud of one of its own. A Black Hawk went down, but rising from that accident was a man born to new life in Christ,” Noble said.

Kathy Mayerscik said last week her son was excited about the prospect of being deployed to Iraq, but that hadn’t yet happened because of Turkey’s wavering support of a U.S.-led coalition against Iraq.

Austin thanked the decorated Army Ranger for his service and prayed he would watch over fallen servicemen who went before him as well as those now fighting overseas.

“Take care of them. Lead them,” Austin said. “Thank you for supporting my soldiers and me. The honor was truly ours.”

Noble also wove together a tapestry of life events Thursday that fashioned the brave soldier, son and brother lost to the Mayerscik family earlier this month.

Kathy Mayerscik had said her son wanted to be a part of the military from the time he was 15. He joined the Army through the deferred enlistment program. And as a member of the 10th Mountain “Polar Bears,” Mayerscik was remembered Thursday as a youngster holding a rifle, seemingly knowing he was cut out for service in the U.S. armed forces.

“He would one day be the right man for the job,” Noble said, drawing a parallel between God’s call to Moses to free and save his enslaved people and Mayerscik’s call to serve the United States.

Noble said the Mayersciks moved from Johnstown to Oil City in the 1990s. Here, a teen-age Shawn Mayerscik – quiet at first – quickly became immersed in his new community, making a legion of friends.

“All the while he (knew) what he was and where he was heading,” Noble said of Mayerscik’s call to serve his country. “We come here to recognize his awesome deeds.”

“I want my brother to be remembered as a hero – not only with the Army, but in his everyday life. … The things he did in his 22 years, most people won’t do their whole lives,” said Mayerscik’s sister, Stacey.

Noble stirred a round of applause during Thursday’s service when calling to mind President Bush’s words late Wednesday to servicemen and women stationed in the Middle East: “Our trust in you is well placed.” He said the applause was to honor U.S. armed forces just one day into Operation Iraqi Freedom, as well as the fallen Mayerscik.

“While it’s out of the ordinary, I would like to begin by thanking you,” Noble said. “We come here to honor, to express our gratitude for someone who was the right man for the job.”

Mayerscik will be buried Thursday, April 3, 2003, in Arlington National Cemetery with full military honors.

Shawn Mayerscik, of Oil City, Pa., shown in this 1999 senior yearbook photo, was among the 11 soldiers who died when their Black Hawk helicopter went down Tuesday, March 11, 2003, in northern New York. (AP Photo/Yearbook photo via The Derrick)

Private First Class Shawn Mayerscik, an Army Ranger, decorated veteran of the conflict in Afghanistan and Oil City native, was killed Tuesday afternoon in a helicopter crash during a training mission in New York state.

Specialist Mayerscik, 22, was among 11 soldiers killed when a UH-60 “Black Hawk” helicopter crashed near Wheeler-Sack Airfield.

Another Pennsylvania soldier, Sergeant John L. Eichenlaub, 24, of South Williamsport, Lycoming County, also was killed.

The soldiers, active members of the 10th Mountain Division stationed at Fort Drum, had just completed a routine assault exercise and were on their way back when the helicopter crashed about three miles from the field.

The accident is being investigated by a team from the Army Safety Center at Fort Rucker, Alabama.

From a young age, Specialist Mayerscik gravitated not only to a career in the military, but with the elite combat forces.

“He always wanted to be a Ranger,” said his father, Stephen Mayerscik. “He admired that they were elite, and that they were the best, that Rangers led the way.”

After graduating from Oil City High School in June 1999, Mr. Mayerscik enlisted in the Army and did basic training at Fort Benning, Georgia. He earned jump wings in the United States, United Kingdom and Ecuador.

Specialist Mayerscik was described as a fanatic about physical fitness and his father said that he took easily to the regimented lifestyle of the military.

“He liked the strict atmosphere. He enjoyed that and he liked the way he was treated. He enjoyed the discipline and could accept it,” Stephen Mayerscik said.

Specialist Mayerscik served primarily in the 75th Ranger Regiment in Seattle and was with it when he was sent to Afghanistan briefly in the fall of 2001 as part of Operation Enduring Freedom. His father said that he didn’t elaborate much about what he’d seen in Afghanistan, except to say that he had participated in helicopter rescues and captures.

“He didn’t want to talk a lot about it,” Stephen Mayerscik said. “But my impression is that he saw a lot of fighting and a lot of action.”

Specialist Mayerscik received a special commendation medal for his service in Afghanistan, to go with the Good Conduct and Army Achievement medals he had already earned.

In November, Specialist Mayerscik was assigned to the 10th Mountain Division.

His parents most recently visited him over Presidents Day weekend before he was to head to South Africa, en route to Turkey. However, the mission was canceled after the Turkish government refused to allow U.S. troops to use their country as a staging area for a northern invasion of Iraq.

Specialist Mayerscik’s commitment to the Army was to expire in November, and he intended to make good on a promise to his father that he would go to college after the military.

He had been accepted to Penn State’s University Park campus for classes in the spring 2004 semester. He intended to study business management with hopes of someday working for the Secret Service.

Funeral arrangements have not been finalized, but Stephen Mayerscik said that a local viewing will be held at Morrison Funeral Home in Oil City, with interment at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia. Mr. Mayerscik is survived by his father, his mother, Kathy, and older sister, Stacey.

Nation Buries War Dead at Arlington

ARLINGTON, Va. – “Taps” is played here two dozen times a day, the notes as haunting and lonely as death, this hallowed ground’s abiding presence.

In Arlington National Cemetery, where the nation buries many of its war dead, horse-drawn caissons bear flag-draped coffins across a sea of white, military-issue tombstones. Buried here are those who served in Vietnam, Korea, the two World Wars, the Civil War, the American Revolution.

Young warriors barely past voting age and old retired vets lie next to each other, grave locations dictated more by logistics than military accomplishment.

“There is no rank structure in death,” says cemetery spokesman Tom Findtner, a line that sounds well-used.

More than 285,000 people are interred in the cemetery’s 624 acres, and 25 to 27 are added each day as the World War II veterans move through their 80s. Also buried here are former presidents, slaves, astronauts and members of Congress. During the height of the Vietnam War, as many as 40 funerals took place daily.

Funerals occur on weekdays, but after the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks they were conducted into the evening and on Saturdays to accommodate victims from the plane crash into the nearby Pentagon.

If U.S. casualties in Iraq — 105 as of Friday — produce a large number of dead, the cemetery would again expand hours, said spokeswoman Barbara Owens.

Burial space is tight, and the cemetery plans to add 43 acres from adjacent military property. Lack of space has brought restrictions on who is eligible for in-ground burials. Relatives are interred in the same plot as their military personnel, where possible, and the cemetery encourages use of the columbarium, a facility for cremated remains.

Some of the dead, like Captain Russell B. Rippetoe, 27, an Army Ranger killed last week when a car bomb exploded at an Iraqi checkpoint, died in military action and came home to the honors accorded a war hero. He was the first U.S. military casualty buried here from the Iraq war.

As befits a place that has been burying heroes since 1864 — pre-Civil War dead were moved here after 1900 — the rituals are many and precise. One, the changing of the guard at the Tomb of the Unknowns, is a major attraction for the 4.5 million tourists who stream through cemetery gates each year.

It was President Kennedy’s televised funeral that gave many Americans their first sight of the horse-drawn caisson, an open-air carriage that carried Kennedy’s coffin here from Washington, just across the Potomac River.

On Thursday, the caisson carrying Rippetoe’s casket was pulled by a team of six matched grays and escorted by a seventh ridden horse as a military band played “Battle Hymn of the Republic” and later, “America the Beautiful.”

Seven soldiers fired rifle volleys — the number of shots depends on the deceased’s rank. Then came “Taps” — played for all funerals — as a lone bugler stepped apart from the band and blew his solitary notes.

Rippetoe’s father, a retired Army officer disabled during Vietnam combat, sat in uniform with his wife Rita as the Army presented them with their son’s posthumous medals, among them the Bronze Star for valor.

The U.S. flag from their son’s casket was folded with military precision. A member of Rippetoe’s unit — 3rd Battalion, 75th Ranger Regiment — presented it to Rippetoe’s father and knelt to recite, in a choked voice, the traditional words intended as solace for those left behind:

“On behalf of the president of the United States and a grateful nation, I present you with this flag as a token of the honor and faithful service of your loved one.”

Joe Rippetoe returned the salutes of his son’s fellow Rangers.

The family received a formal condolence card from a member of the Arlington Ladies, a women’s group that sends someone to every funeral. That tradition began in 1972 after an Army General happened on a burial with no mourners.

Even as Rippetoe’s funeral was ending, another was beginning. On a road nearby was parked a yellow backhoe, its driver waiting for the mourners to leave so the more practical tasks of burying the dead could go forward.

Rippetoe’s grave — No. 7860, Section 60 — is in an area where reminders of war’s cost in young lives are inescapable. Behind his is a grave with the remains of two soldiers killed when their helicopter was downed in Southeast Asia in 1971.

Next to Rippetoe lie Sergeant Joshua M. Harapko, 23, and Private First Class Shawn A. Mayerscik, 22, killed in a March 11 helicopter crash at Ft. Drum, N.Y. Their graves, like his, are too new to have received the tab-shaped white marble markers that are standard issue here.

Funerals are scheduled next week for more Iraq casualties, among them Marine Second Lieutenant Frederick E. Pokorney Jr., 31, who died March 30 in an ambush near Nasiriyah. Like Rippetoe, who coordinated artillery from the ground, Pokorney had a dangerous field artillery job.

Pokorney’s uncle, Richard Schulgen, said in an interview his nephew had wanted the honor of being buried at Arlington, where a grandfather and great uncle are also laid to rest. An enlisted man, Pokorney had recently become a commissioned officer and was proud of his service to his country.

“He was proud of what he was doing and proud of his family, a hardworking guy — the best guy you can ever know,” said Schulgen. “I hope the American people don’t forget.”

Here, they don’t.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard

Shawn Mayerscik, of Oil City, Pa., shown in this 1999 senior yearbook photo, was among the 11 soldiers who died when their Black Hawk helicopter went down Tuesday, March 11, 2003, in northern New York. (AP Photo/Yearbook photo via The Derrick)

Shawn Mayerscik, of Oil City, Pa., shown in this 1999 senior yearbook photo, was among the 11 soldiers who died when their Black Hawk helicopter went down Tuesday, March 11, 2003, in northern New York. (AP Photo/Yearbook photo via The Derrick)