Quentin C. Aanenson (April 21, 1921–December 28, 2008) was a World War II veteran fighter pilot and former Captain of the 391st Fighter Squadron, 366th Fighter Group, 9th Air Force, U.S. Army Air Corps. He flew the P-47 Thunderbolt in the Normandy D-Day invasion and subsequent European campaign.

Aanenson enlisted in the United States Army Air Corps in 1942 but was not called up to active duty until February 1943. He left for Santa Ana Air Force Base for pre-flight training and then to Primary Flight School at Thunderbird Field near Phoenix, Arizona. In September 1943, he left for Basic Flight School at Gardner Field near Bakersfield, California. Aanenson then left for Advanced Flight Training at Luke Field, Phoenix, Arizona where he was commissioned a second lieutenant on January 7, 1944. From January to May 1944, he trained at Harding Field in Baton Rouge, Louisiana where he met his wife Jackie.

Aanenson demonstrated exceptional courage and ability as a fighter pilot, amassing tens of kills and beating all odds to survive the early months of his tour of duty. Later in the war, Aanenson was taken out of the cockpit, embedded with advance troops, and his skills put to good use as a quick-response aircraft attack co-ordinator. He eventually documented his experiences for his family. This was later turned into a documentary video which he wrote, produced and narrated. “A Fighter Pilot’s Story” was first televised on 11 December or 12 November 1993, then broadcast on over 300 public television stations in June 1994. Up until August 2007, it was available for purchase on DVD. The three-hour documentary, made all the more effective by being narrated throughout in his flat, affectless voice, tells of a young, enthusiastic, cheery boy very rapidly aged by too much death. It also tells of a remarkably wide range of combat duties, and details many harrowing individual missions, like the one where he and his wing man came upon a German convoy, destroyed the vehicles, and when his wing man’s guns jammed, how Aanenson worked-over the roadside ditches where the convoy soldiers had hidden, making multiple passes, “walking” his rudder to spread his fire more effectively, so that there would be as few survivors as possible.

The documentary also tells of a remarkable coincidence, where his P-47 was called down to assist some American troops under attack by a tank. He surveyed the scene, then reported to the troops that the tank was just too near, there was too much chance that he would hit them instead of the tank. The officer in command told him to come on in anyway, since they were going to be dead if the tank wasn’t stopped. He managed to destroy the tank cleanly, then recounts how he was telling this story to his new neighbor after the war, and the man finished the story for him, then thanked him for saving his life.

Aanenson is a Commander of the French Legion of Honor, representing all Americans who served in France. He was also featured in the documentary The War by Ken Burns, recounting his experiences during World War II as a fighter pilot. At the conclusion of Episode 5 of the series, he narrated a poignant and ominous letter written by him to his future wife, considered by some critics to be of similar style to the Sullivan Ballou letter in Burns’ The Civil War. Written December 5, 1944, but never sent, the letter reads:

“ Dear Jackie,

For the past two hours, I’ve been sitting here alone in my tent, trying to figure out just what I should do and what I should say in this letter in response to your letters and some questions you have asked. I have purposely not told you much about my world over here, because I thought it might upset you. Perhaps that has been a mistake, so let me correct that right now. I still doubt if you will be able to comprehend it. I don’t think anyone can who has not been through it.

“I live in a world of death. I have watched my friends die in a variety of violent ways…

“Sometimes it’s just an engine failure on takeoff resulting in a violent explosion. There’s not enough left to bury. Other times, it’s the deadly flak that tears into a plane. If the pilot is lucky, the flak kills him. But usually he isn’t, and he burns to death as his plane spins in. Fire is the worst. In early September one of my good friends crashed on the edge of our field. As he was pulled from the burning plane, the skin came off his arms. His face was almost burned away. He was still conscious and trying to talk. You can’t imagine the horror.

“So far, I have done my duty in this war. I have never aborted a mission or failed to dive on a target no matter how intense the flak. I have lived for my dreams for the future. But like everything else around me, my dreams are dying, too. In spite of everything, I may live through this war and return to Baton Rouge. But I am not the same person you said goodbye to on May 3. No one can go through this and not change. We are all casualties. In the meantime, we just go on. Some way, somehow, this will all have an ending. Whatever it is, I am ready for it.

Quentin ”

The painting Thunderbolt Patriot by William R. Farrell, now in the permanent collection of the Smithsonian Institution of the National Air and Space Museum, depicts Aanenson having just returned from a combat mission over Germany during World War II. An airfield in Luverne, Minnesota was named in his honor after him Quentin Aanenson Field Airport (KLYV).

Aanenson died from the effects of cancer at his home in Bethesda, Maryland, December 28, 2008.

QWII Fighter Pilot Shared Haunting Story With the World

By Patricia Sullivan

Courtesy of The Washington Post

Tuesday, December 30, 2008

As a fighter pilot in World War II, Quentin C. Aanenson fought a very dangerous war.

He first saw combat on D-Day, and in the ensuing year, he dive-bombed and strafed tanks, bridges and German infantry at low altitude. He took direct hits from antiaircraft shells and flak on more than 20 missions and survived two crash landings. He watched so many of his fellow pilots in the 366th Fighter Group die that he stopped making friends with the replacements.

After 75 combat missions, Mr. Aanenson rotated home for a short break. He married the girl he’d met during basic training and went to see his parents in his southwestern Minnesota home town. There, he picked up his boyhood hunting rifle and shot a pesky gopher. As he watched it die, “something snapped,” he said. “I resolved never to kill again.”

Fortunately, he was never asked to. By the time he was due back for duty, the war was over.

Mr. Aanenson, 87, who became a life insurance executive after the war, died of cancer December 28, 2008, at his home in Bethesda, Maryland.

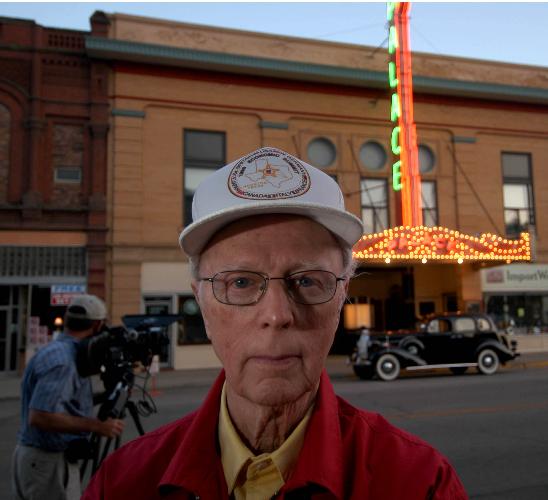

A trim, modest man who looked like the unassuming grandson of Norwegian immigrants that he was, Mr. Aanenson’s reflections on the brutality of combat deepened the understanding of war among millions of television viewers. He had rarely spoken of his military service until after he retired, when his children suggested that he document what he’d gone through.

The result became a movie, “A Fighter Pilot’s Story,” which he intended as a private family memoir. In 1992, he showed the video to a reunion of the 366th Fighter Group Association. Fellow veterans urged him to get it into wider distribution. WETA aired a three-hour version in November 1993. By that June, the 50th anniversary of D-Day, more than 300 PBS stations had broadcast it.

Filmmaker Ken Burns heard about the video while he was researching his World War II documentary. His interviews with the eloquent Mr. Aanenson led Burns to Minnesota, where he found a treasure-trove of wartime newspaper columns written by the editor of the local Rock County Star Herald. How the farm town dealt with the loss and heroism of its sons formed the narrative underpinning of Burns’s 2007 documentary, “The War.”

A principal officer at Mutual of New York for 32 years, Mr. Aanenson received some of his profession’s highest managerial honors. He was selected its “Manager of the Year” from a field of 147 before his retirement in 1986.

“That helped me come to peace — this sounds strange — with the dealing in death,” he later said of his career in life insurance. “You have to choose life over death. I don’t mean to be melodramatic about it, but that was the motive.”

But the war never entirely left him. He was haunted by the fear that he had once mistakenly fired on Allied troops. The first time he fired on a column of German soldiers along a roadside, the impact of his shells pitched their bodies into the air. He knew he was doing what he was trained to do, “but when I got back home to the base in Normandy and landed, I got sick. I had to think about what I had done. Now that didn’t change my resolve for the next day. I went out and did it again. And again and again and again,” he said.

He wrote affecting letters to his fiancee, not all of which he mailed. Later in life, after nightmares kept him from sleep, his right hand, the one that controlled the fighter’s guns, would not work well enough to hold a coffee cup. Blinding headaches from a wartime concussion plagued him for decades.

Born April 21, 1921, on a 160-acre farm five miles from Luverne, Minnesota, Quentin Aanenson grew up dreaming of flight. He spent two years at the University of Minnesota, and in the summer of 1941 moved to Seattle, where he got a job at Boeing and attended the University of Washington. Pearl Harbor was attacked in December, and the United States entered World War II.

Although Mr. Aanenson had hoped to become a pilot, he was disqualified because of colorblindness. But he took the eye test enough times to memorize it, and by 1943 was accepted into the U.S. Army Air Forces. After flight training and fighter pilot training, he was sent to England. His first combat mission was June 4, 1944, flying his P-47 Thunderbolt to Normandy, where he was among those who attacked the German positions behind Pointe du Hoc in advance of the Allies’ landing.

Almost a year of vicious combat awaited him. In July 1944 over Rouen, France, he took a direct hit from an antiaircraft shell that failed to explode. On August 3, 1944, on a mission over Vire, France, his plane was hit by flak and caught fire. Unable to bail out, he dived straight toward the earth, and the high-speed plunge extinguished the flames. He managed to line up with a nearby runway and crash-landed, blowing a tire, damaging the landing gear and spinning the fighter around until it broke in two. Mr. Aanenson dislocated his shoulder, cracked three ribs and whacked his skull against the gunsight. He was pulled, unconscious, from the wreckage. Ninety minutes later, a photographer for Picture Post, a prominent English photojournalistic magazine, captured the bruised and battered pilot beside his collapsed fighter.

As soon as he recovered, he flew again. During the Battle of the Bulge, he coordinated close air support on the ground. For 36 hours, he and his radio man were trapped behind enemy lines in the Ardennes.

After the war ended, he graduated from Louisiana State University and joined the life insurance company where he spent his entire career. He moved to Bethesda in 1956 and had lived in the same house since then.

Among his military awards were the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Purple Heart and the Air Medal with nine oak leaf clusters. Fifty years after the liberation of France, Mr. Aanenson was made a commander of the Legion of Honor, an honor he accepted, he said, on behalf of all American pilots, living and dead, who served in the war. His home town renamed its airport Quentin C. Aanenson Field.

Survivors include his wife of 63 years, Jacqueline G. Aanenson of Bethesda; three children, Vicki J. Murphy of Ellicott City, Jerry L. Aanenson of Boyds and Debra D. Pyers of Chicago; a brother; a sister; and nine grandchildren.

He told The Washington Post in 2007 that he considered himself “just damn lucky.”

“It’s hard to understand why the guy next to you was blown apart and why you’re able to go on to have a wonderful life,” he said. “There’s a sense of responsibility we assume, or should assume. I tried to make a contribution, to my family, to the business world, to live with high ethical standards . . . not to waste this life, to do something that counts in a positive way. . . . I tried to live with purpose.”

On Sunday, December 28, 2008, QUENTIN C. AANENSON of Bethesda, Maryland. Beloved husband of Jacqueline G. Aanenson; devoted father of Vicki J. Murphy, Jerry L. Aanenson and Debra D. Pyers; dear brother of Curtis Aanenson and Mavis Porter;. loving grandfather of Derek, Kyle and Ryan Curtis Murphy, Shanna and Brett Pyers, Trent, Hunter and Lindsay Aanenson and Troy Muller; father-in-law of Harry T. Murphy, Thomas L. Pyers and Julia C. Aanenson.

Friends may call at JOSEPH GAWLER’S SONS, INC., 5130 Wisconsin Avenue, N.W. (at Harrison Street) on Friday, January 2, 2009 from 2 to 4 and 7 to 9 p.m. Services will be held at Concord St. Andrew’s United Methodist Church, 5910 Goldsboro Road, Bethesda, Maryland on Saturday, January 3, 2009 at 1 p.m.

Interment with Full Honors will be held at Arlington National Cemetery on Friday, February 27, 2009 at 3 p.m.

Memorial contributions may be made in his name to the Montgomery Hospice, 1355 Piccard Drive, Suite 100, Rockville, Maryland 20850.

Michael Robert Patterson was born in Arlington and is the son of a former officer of the US Army. So it was no wonder that sooner or later his interests drew him to American history and especially to American military history. Many of his articles can be found on renowned portals like the New York Times, Washingtonpost or Wikipedia.

Reviewed by: Michael Howard